Newspapers covered every day of the lives of our ancestors and the history that was unfolding around them. Obituaries contain the stories of our lives. The details and clues obituaries contain pull us in to start digging deeper and learning more about each person and the towns where they were born, lived and died.

Some are brief, some are lengthy – but one by one our stories are preserved and passed down to future generations in obituaries. A lot can be packed into just a few lines.

How long have obituaries and death notices been published in America?

Since paper and presses were available.

The earliest newspapers in America were generally two folded broadsheets that provided the reader with four pages.

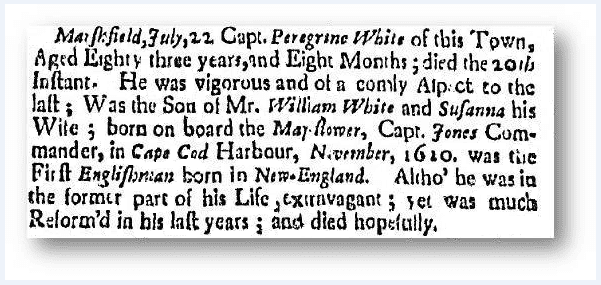

Astonishingly, obituaries in American newspapers go back to the days of our earliest settlers that arrived on the Mayflower. GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives include the obituary of Peregrine White (1620-1704) – who was born onboard the Mayflower in 1620 – down through the hundreds of millions of obituaries that have been published across the centuries, right down to today.

Have newspaper obituaries changed over the last 300 years?

Yes and no.

Newspapers have grown from the standard 4-page, folded newspaper to daily papers that can have upwards of 40, 50 or 60 pages. With more space and the ease of automated typesetting and computers, obituaries now can cover multiple column inches in a newspaper – complete with photos and detailed mini-biographies written by the family. Obituaries have come a long way from the few lines written about Peregrine White to today.

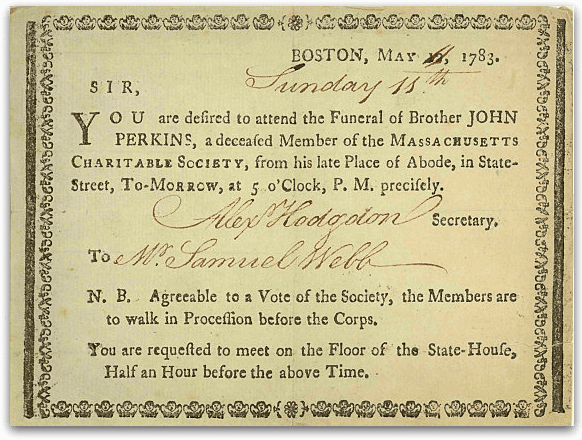

Not every issue of every newspaper has survived – but sometimes the additional printed material distributed at the time of a person’s death and funeral has survived.

Here is an early example of a death notice card, printed as a note card to alert friends to the death and pending funeral of the late John Perkins, who died in 1783.

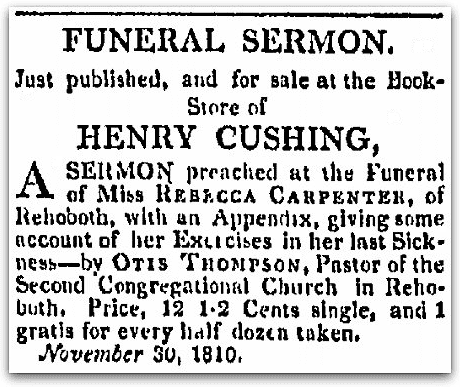

Another example of surviving material is this ad related to my distant cousin, 14-year-old Rebecca Carpenter (1796-1810). The issue of the newspaper that carried her obituary when she died 18 September 1810 has not survived, but an advertisement announcing the availability of copies of the sermon preached at her funeral did.

As a courtesy and keepsake for the family and friends, funeral sermons were commonly transcribed, published and distributed – usually in very small press runs. This practice widely continued from the 1700s to the mid-1800s. Bookseller Henry Cushing, ever one to promote his stock, offered these sermons at a bargain rate – 12 ½ cents per copy – but if you bought 6 copies, he would give you a 7th copy free.

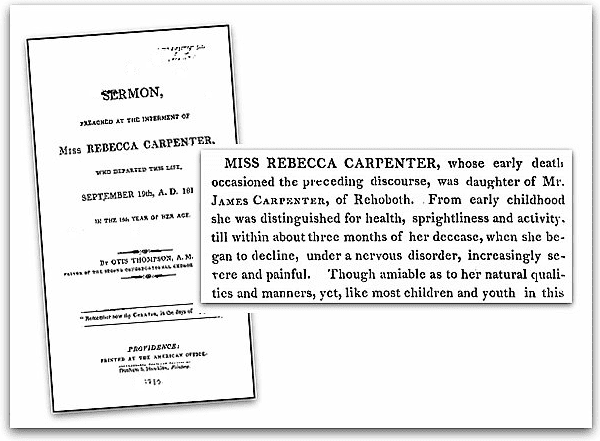

Remarkably, Rebecca Carpenter’s funeral sermon itself has also been preserved, and can be found online. It gives us a brief glimpse of her short life.

Published funeral sermons are the forerunner of the lengthy obituaries that we are used to today. While death notices in early American newspapers were kept brief because of space constraints, the invention of the linotype machine in the late 1800s allowed editors to expand the page count of newspapers – and obituaries expanded right along with them.

The sermons and eulogies given at funerals are still frequently published today as “memorials” and “In Memoriam’ volumes. These generally follow the format of funeral sermons and include a brief biography of the deceased and the testimonial talks given at their memorial service.

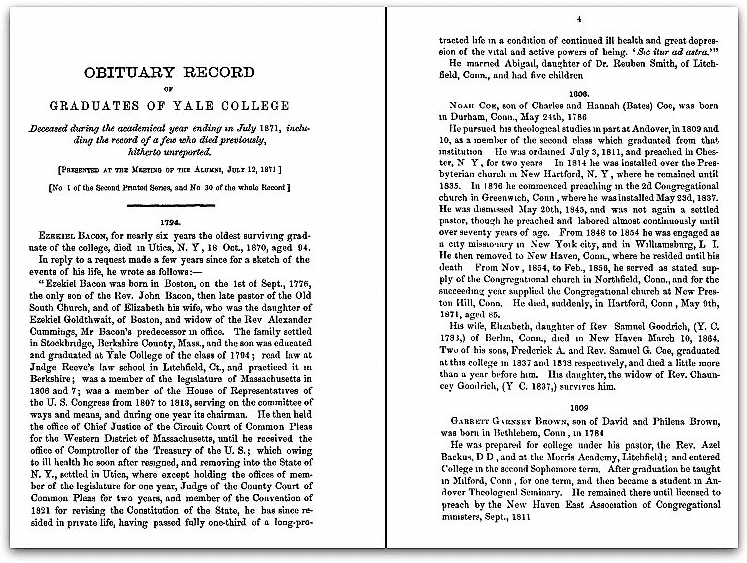

It is also common to see lengthy biographical memorials published by professional and alumni associations. For example, Yale University has put online the obituaries of their graduates that were published in the annual volumes of the Yale Obituary Record from 1859-1952. These detailed biographical and genealogical obituaries often give details about multiple generations of each person’s family.

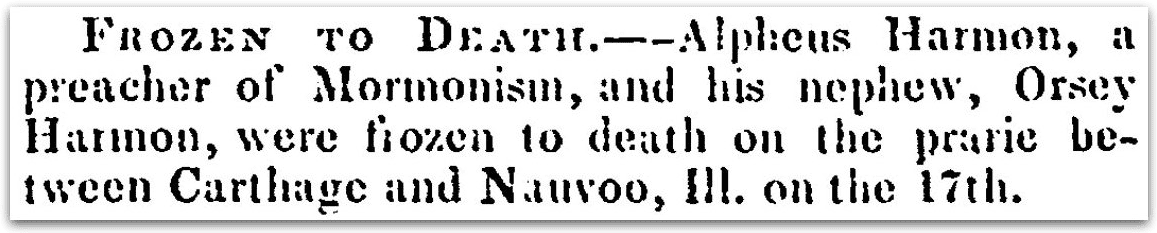

A lot can be packed into just a few lines.

Like these few lines written about Alpheus and Orsey Harmon, who were found “frozen to death on the prairie between Carthage and Nauvoo, Illinois” on 17 December 1842. Alpheus was described as a “preacher of Mormonism.” He had been called to preach the Gospel in 1841, and on his return home in 1842 was trapped in a snow storm that killed him.

Sometimes those stories are recorded in newspapers published miles from where our ancestors lived. News of the Harmons’ deaths in Illinois was published in the New Hampshire Sentinel in Keene, New Hampshire – over 1,100 miles away.

Remarkable. Unforgettable.

No matter how brief the obituary, its details give us clues to more information about our ancestors’ lives and even to their extended family tree.

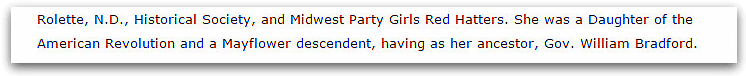

Marilyn Guedesse was born in Minot, North Dakota, 31 March 1933, and died in Hamilton, Illinois, 20 December 2015. I never met her, her husband, parents or descendants – but when I read her obituary I knew she was my cousin.

How?

The family included in her obituary the fact that she was a descendant of Mayflower passenger Governor William Bradford – since he is my ancestor, that makes us cousins.

Obituaries are a great source for bringing together the branches of the family tree – not only by listing the current, recent generations, but by naming their ancient ancestors like this obituary did.

Related Articles: