Introduction: In this article – as everyone is filling out the 2020 Census – Gena Philibert-Ortega provides tips for using the census in your family history research. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

Have you received your 2020 Census invitation in the mail? Family historians are posting on social media about the census and how excited they are to be a part of history – but disappointed in the lack of detailed questions for our descendants to discover. Even though we genealogists rely heavily on the census for putting our ancestors in place and time, in reality the census has a specific government purpose and isn’t done for the benefit of genealogists (I know, we wish it were).

As we participate in the latest decennial census, there are a few things we need to keep in mind about the historical censuses we use for research.

Not Everyone Loved the Census

Historically, not everyone was thrilled with the government asking a bunch of personal questions (not everyone is thrilled about it now). People have always had differing opinions about answering personal questions and what those answers could be used for. That might be something to consider as you look at answers from old censuses that might not seem quite right.

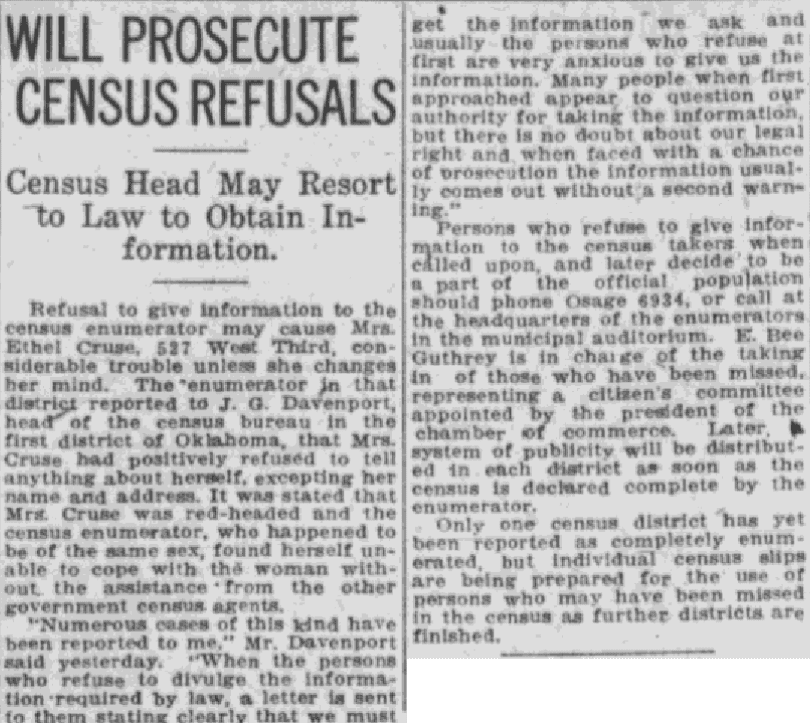

Yes, there was a penalty for those who didn’t cooperate. Some of those people might even be found in the newspaper, such as this article about Mrs. Ethel Cruse of 527 West Third in Tulsa, Oklahoma. I wonder if having her refusal printed in the newspaper may have been worse than just answering the census enumerator’s questions.

The Information Is Not Always Accurate

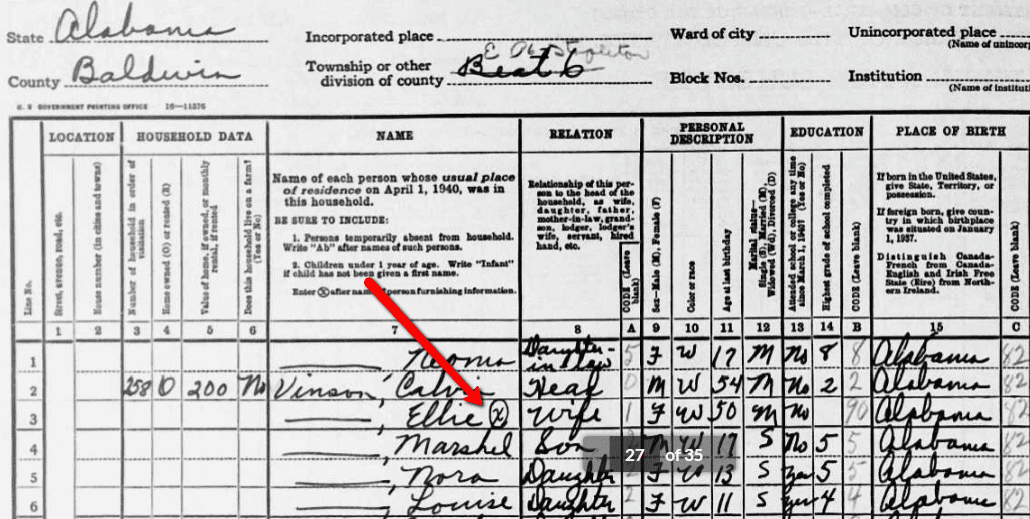

Not everyone loved the census, which led to inaccurate information – but there’s another reason why you can’t assume everything on the census is correct. The problem with the census returns prior to 1940 is that we have no idea who answered the enumerator’s questions. That means we have no way to judge the accuracy of the information based on the informant.

Genealogy Tip: The 1940 census includes an “x” inside a circle to indicate who the informant was for that household.

Even if we know who the informant is, that doesn’t mean the information is necessarily correct. One of the “white lies” researchers report seeing on the census is that some women appear to grow younger every 10 years instead of aging in each census appearance!

Sure, our ancestors may have lied about their age on the census. Afterall, who wants a stranger to know how old you really are? But was it grandma pretending to be younger than she was, or was it her daughter answering a question with what she believed was correct? Or did grandma really have no idea how old she was since she had no birth certificate? Any of those scenarios could be true.

Information on the census could be wrong due to indifference or lack of knowledge. But there are even more reasons for census misinformation. Individuals aren’t the only ones who provided incorrect information. Sometimes a territory added misinformation to help their cause for statehood.

The 1857 Minnesota Territory census includes fictional people and places. (1) Some Utah polygamous families were listed in such a way that they looked like individual families during the 1880 census. This was at a time when Utah was being pressured to stop the practice of polygamy by the U.S. government. (2)

It’s important that, as we research, we don’t use the census as our only piece of information for facts such as age, naturalization status, and marital status (some people may be listed as widows instead of divorced).

We Sometimes Don’t Take a Complete Look

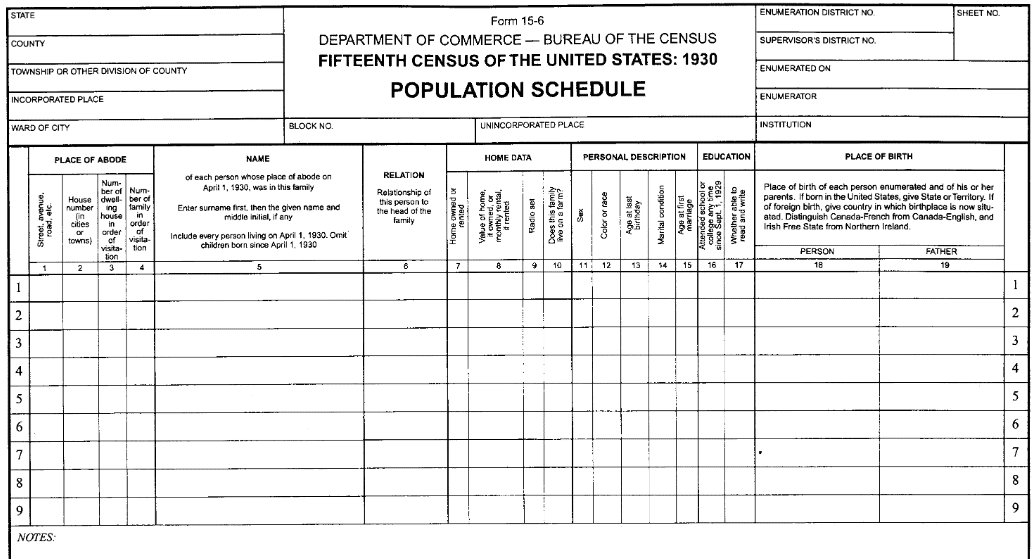

Did you know that Box 30 on the 1910 census asked if the person being enumerated was a survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy? For those who were farmers, Box 29 on the 1920 population schedule provides a space to indicate the person’s number on the farm schedule.

The census is one of those often-used records that we really don’t study as carefully as we should.

To better understand what is on each census, make sure to download the blank forms which make the columns much easier to read. You can find these on the Resources for Genealogists page of the National Archives website.

Ready to Leave Your Mark?

I love the idea of participating in something that my ancestors participated in, and that will be of interest to a family history researcher in the future. Because we have to wait 72 years for the information to be made public, I made copies of our family’s completed 2010 census form so that someday my sons could see the answers I provided when they were kids. It’s important that we fill out the census, but we also need to remember that the census wasn’t meant to be a genealogical record – and our ancestors definitely didn’t think of it that way, so make sure in your research to learn more about the census and use it with other records, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, to get a complete picture of your ancestors’ lives.

Genealogy Tip: You can access the U.S. Federal Census from the GenealogyBank homepage.

__________________

(1) “Minnesota Census,” FamilySearch Research Wiki (https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/Minnesota_Census: accessed 17 March 2020).

(2) “False Census Entries” in Census Records chapter, The Source. Accessed on Google Books (https://books.google.com/books?id=Jw3kn_AgNTkC&lpg=PA164&ots=2O1x2tvaSI&dq=genealogy%20census%20with%20state%20that%20had%20fake%20people%20for%20statehood&pg=PA164#v=onepage&q=genealogy%20census%20with%20state%20that%20had%20fake%20people%20for%20statehood&f=false: accessed 17 March 2020).

Related Articles: