On 16 March 1850, Nathaniel Hawthorne published one of the classics in the history of American literature: The Scarlet Letter. This novel, with its risqué story of an adulterous affair between a married woman and the local minister set in 17th century Puritan New England, combined with the author’s gentle and dignified portrayal of the adulterous woman Hester Prynne, was certain to cause controversy. And it did – but not for its subject matter.

In fact, the public and critics alike loved the story, and The Scarlet Letter was an instant best-seller. After the initial print run sold out, a large (for the times) second run of 2,500 copies was printed – and it sold out in ten days! The book continues to be read today, and is a mainstay of American literature classes.

So what caused the controversy, if not the story itself? Nearly-universal condemnation was expressed for an indulgence Hawthorne allowed himself: he had an axe to grind, and he wrote an extensive preface to his book so that he could publicly air his grievance.

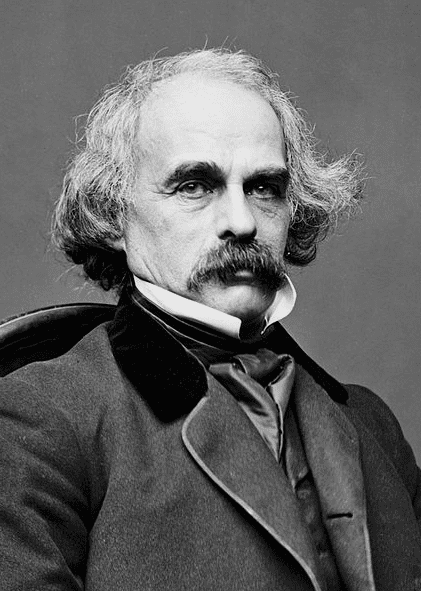

Hawthorne came from a long-established Salem, Massachusetts, family. His ancestor William Hathorne (Nathaniel added the “w” to the family name) was one of the early Puritans involved in the 17th century Massachusetts Bay Colony. The next generation of the family, John Hathorne, was one of the judges during the notorious Salem Witch Trials – and the only judge who never repented for the wrongs the community did to those innocent women.

Nathaniel Hawthorne (originally Hathorne) was born in Salem, and he lived there when writing The Scarlet Letter. At that time, he worked in the Salem Custom House to support his family.

Hawthorne’s three-year tenure at the Salem Custom House was abruptly terminated when the Whig candidate Zachary Taylor won the presidential election of 1848. Because he was a Democrat Hawthorne lost his job – causing him deep bitterness.

Seeking revenge, he wrote a preface to The Scarlet Letter that vented his anger, making personal attacks on officials in Salem that upset the community and people throughout the country – as seen in the second newspaper article reprinted below.

The following two newspaper articles are about the publication of The Scarlet Letter. The first article shows how well the story was received and liked – but the second article expresses extreme displeasure and disappointment at the personal attacks in Hawthorne’s preface.

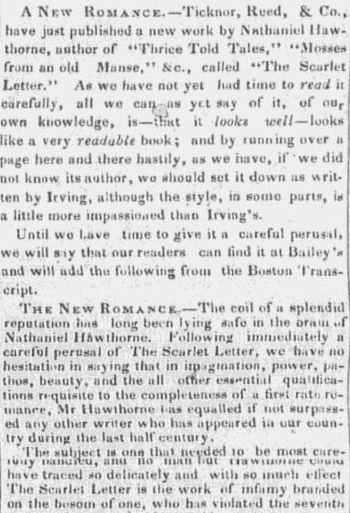

Here is a transcription of this article:

A New Romance

Ticknor, Reed, & Co. have just published a new work by Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of “Thrice Told Tales” [correction: “Twice Told Tales” – ed.], “Mosses from an Old Manse,” &c., called “The Scarlet Letter.” As we have not yet had time to read it carefully, all we can as yet say of it, of our own knowledge, is—that it looks well—looks like a very readable book; and by running over a page here and there hastily, as we have, if we did not know its author, we should set it down as written by [Washington] Irving, although the style, in some parts, is a little more impassioned than Irving’s.

Until we have time to give it a careful perusal, we will say that our readers can find it at Bailey’s and will add the following from the Boston Transcript:

The New Romance

The coil of a splendid reputation has long been lying safe in the brain of Nathaniel Hawthorne. Following immediately a careful perusal of “The Scarlet Letter,” we have no hesitation in saying that in imagination, power, pathos, beauty, and all the other essential qualifications requisite to the completeness of a first-rate romance, Mr. Hawthorne has equaled if not surpassed any other writer who has appeared in our country during the last half century.

The subject is one that needed to be most carefully handled, and no man but Hawthorne could have traced [it] so delicately and with so much effect. “The Scarlet Letter” is the work of infamy branded on the bosom of one who has violated the seventh Commandment, and, side by side with the partner of her guilt, the sad heroine walks through a life of retribution crowded with incidents which the novelist has depicted with so much truth and vigor that the interest at every page of his book grapples to the reader with a powerful hold upon his sympathy, and he will not lay down the story till he knows its result at its close. As a great moral lesson this novel will outweigh in its influence all the sermons that have ever been preached against the sin, the effects of which “The Scarlet Letter” is written to exhibit.

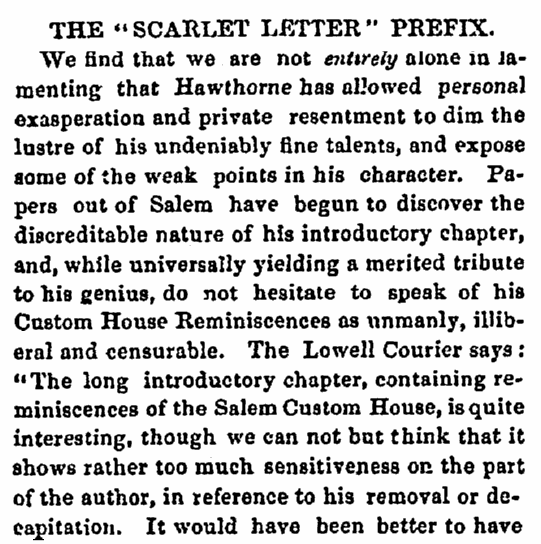

Here is a transcription of this article:

The ‘Scarlet Letter’ Prefix

We find that we are not entirely alone in lamenting that Hawthorne has allowed personal exasperation and private resentment to dim the luster of his undeniably fine talents, and expose some of the weak points in his character. Papers out of Salem have begun to discover the discreditable nature of his introductory chapter, and, while universally yielding a merited tribute to his genius, do not hesitate to speak of his Custom House Reminiscences as unmanly, illiberal and censurable.

The Lowell Courier says:

“The long introductory chapter, containing reminiscences of the Salem Custom House, is quite interesting, though we cannot but think that it shows rather too much sensitiveness on the part of the author, in reference to his removal or decapitation. It would have been better to have omitted all his charges and insinuations against the Whig party.”

The Boston Bee remarks:

“We have not had time to peruse this much-vaunted production, but hear that its preamble is replete with personal reflections on the functionaries at the Salem Custom House, and illiberal flings of censure at the Whig party. This is censurable in an author whose literary position should place him above the dictates of revenge because he, in his turn, was a victim to change of administration.”

The Boston Journal concludes a highly complimentary notice of “The Scarlet Letter” by saying:

“We cannot but regret that the author did not take counsel with discreet friends, before prefixing to his charming romance some sixty pages, in the shape of a preface, of matter as entirely irrelevant as would be a description of the household arrangements of the Emperor of China. Under the text of Reminiscences of the Salem Custom House, the author has dragged before the public, and held up to ridicule, individuals, whose greatest peculiarity was that they could not sympathize with the dreamy thoughts and the literary habits of the author. Mr. Hawthorne evidently keenly feels that his talents and personal importance were not appreciated by his fellow-officials and by the citizens of Salem, and he takes a paltry revenge in lampooning his former associates. There is a vein of bitterness running through this portion of the work, which, though covered under an assumed playfulness of language, is by no means concealed. The whole chapter, from beginning to end, is a violation of the courtesies of life, and an abuse of the privileges of common intercourse.”

Even the Transcript ventures to whisper that:

“Mr. Hawthorne seems to have given great offence to the good people of Salem, by his portraits of the gentlemen with whom he was associated in the custom-house.”

The Mail expresses itself thus:

“The Romance itself is considered a good one – first rate, indeed; but the author has seen fit to preface it with some fifty pages of extraneous matter, in which he makes covert attacks on private individuals in Salem, apparently in revenge of some of his own private griefs and disappointments. This is wrong, and the publishers ought to have insisted upon its being expunged from the work. If Mr. Hawthorne wishes to “write a book” against his enemies, let him do so manfully and openly, and not interlope his attacks in a Romance, intended for universal circulation among those who have no desire to be troubled with his private connections or personal peccadilloes.”

The New York Express, of Friday, says:

“Nathaniel Hawthorne has written a book, called “The Scarlet Letter,” attracting much comment and little commendation, from the fact, it is said, that he has introduced the affairs of private life to public discussion. If so, it is a matter of deep regret, for no writer, of his class, in the nation, enjoyed a more enviable position than N.H.”

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Article: