Missouri was one of the four slave-holding states (along with Delaware, Kentucky and Maryland) that stayed in the Union during the Civil War, deciding not to secede and join the 11 other slave-holding states that formed the Confederate States of America. However, the question of loyalty to the Union or the Confederacy embroiled Missouri in violence throughout the war, most of it in the form of ruthless guerrilla warfare. Abolitionist and pro-slavery forces raided one another, causing much destruction of property and loss of life.

Missouri was a key state for both sides at the start of the Civil War. Its governor, Claiborne Fox Jackson, wanted secession. However, like Kentucky, Missouri declared neutrality, meaning it would not leave the Union – yet would not supply men or arms to either side. With a population of 1.2 million, Missouri would have been the most populous state in the Confederacy if it had seceded (with the exception of Virginia).

It had a well-developed industrial base in St. Louis, and controlled the Missouri River and an important stretch of the Mississippi River. As a Confederate state it would have blocked off Kansas and threatened southern Illinois. It was a prize the Confederacy dearly wanted.

Missouri men loyal to the South rallied under General Sterling Price, known affectionately as “Old Pap.” Throughout 1861 there were a series of skirmishes in Missouri, with the Confederates winning the most important clash (the Battle of Wilson’s Creek on 10 August 1861), defeating a Federal army of 6,000 men and killing its commander, General Nathaniel Lyon. Price and his men sporadically occupied Springfield and other areas in southwestern Missouri, but by early 1862 had retreated into Arkansas.

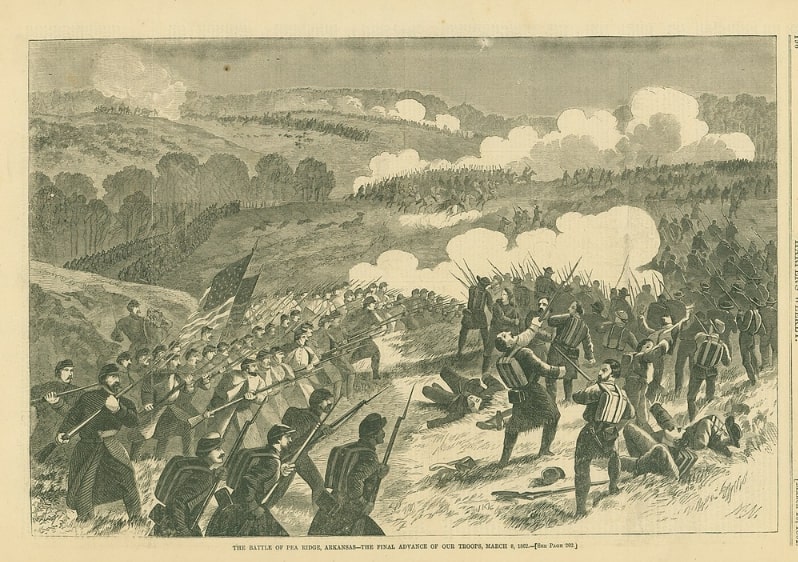

Then, in the pivotal Battle of Pea Ridge (Elkhorn Tavern) on 6-8 March 1862, a smaller Union army under General Samuel R. Curtis decisively defeated a larger Confederate army under General Earl Van Dorn in northwestern Arkansas, effectively placing Missouri under Union control for the rest of the war.

Despite this, Missouri remained a battleground for the next three years as Confederate guerrilla bands under leaders such as William Quantrill and “Bloody Bill” Anderson continued to fight for Missouri. Six of their teenaged troops, Frank and Jesse James, and Bob, Cole, Jim and John Younger, refused to accept peace even after the Civil War ended, forming the notorious James-Younger Gang.

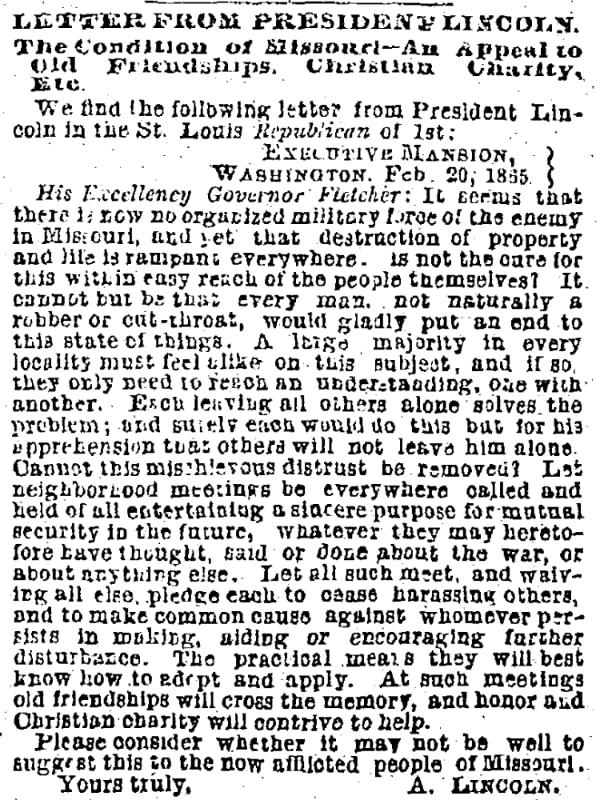

As the Civil War was drawing to a close a weary President Abraham Lincoln wanted the violence in Missouri to end, but knew he could not afford to divert a large number of troops from the Eastern Theater of the war to quell the fighting in Missouri. Instead, he wrote to Governor Thomas Clement Fletcher on 20 February 1865, suggesting that the governor urge Missouri’s citizens to take matters into their own hands, police themselves, and stop the violence by relying on “old friendships” and “Christian charity.”

Lincoln’s letter appeared in the St. Louis Republican and was reprinted by the Daily Age (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) on 5 April 1865.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Letter from President Lincoln.

The Condition of Missouri – An Appeal to Old Friendships, Christian Charity, Etc.

We find the following letter from President Lincoln in the St. Louis Republican of [April] 1st:

Executive Mansion, Washington.

Feb. 20, 1865.His Excellency Governor Fletcher:

It seems that there is now no organized military force of the enemy in Missouri, and yet that destruction of property and life is rampant everywhere. Is not the cure for this within easy reach of the people themselves? It cannot but be that every man, not naturally a robber or cut-throat, would gladly put an end to this state of things. A large majority in every locality must feel alike on this subject, and if so, they only need to reach an understanding, one with another. Each leaving all others alone solves the problem; and surely each would do this but for his apprehension that others will not leave him alone. Cannot this mischievous distrust be removed? Let neighborhood meetings be everywhere called and held of all entertaining a sincere purpose for mutual security in the future, whatever they may heretofore have thought, said or done about the war, or about anything else. Let all such meet, and waiving all else, pledge each to cease harassing others, and to make common cause against whomever persists in making, aiding or encouraging further disturbance. The practical means they will best know how to adopt and apply. At such meetings old friendships will cross the memory, and honor and Christian charity will contrive to help.

Please consider whether it may not be well to suggest this to the now afflicted people of Missouri.

Yours truly,

A. Lincoln

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: Abraham Lincoln, by Alexander Gardner, 8 November 1863. Credit: Mead Art Museum; Wikimedia Commo