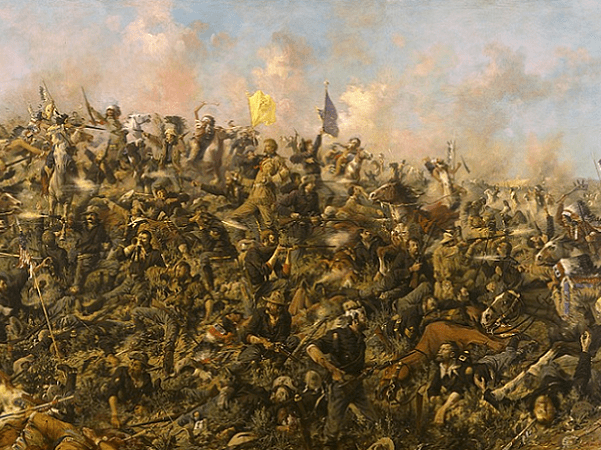

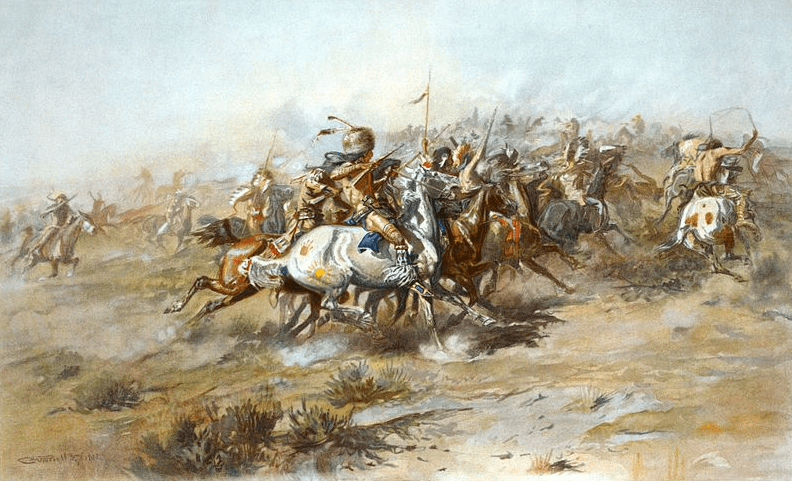

On 25 June 1876 a force of around 2,000 Lakota, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors, fiercely defending their combined village on the Little Bighorn River in Montana Territory, stopped a surprise attack from 600 men of the U.S. 7th Cavalry led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. When the dust finally settled from the furious fighting, Custer and every man of the five companies he was leading lay dead, with the 7th Cavalry’s other seven companies pinned down and unable to come to his aid.

U.S. forces lost 268 men that day, including 31 officers and 10 scouts, and another 55 were wounded in the legendary battle. History will never know how many Indians died during the fighting, with estimates ranging from 40 to 140. One thing is certain, however: the Battle of the Little Bighorn was a complete disaster for Custer, and is known as “Custer’s Last Stand.”

The battle remains one of the most famous in American history, and one of the most controversial. Was Custer the victim of bad luck, overwhelmed by superior numbers through no fault of his own? Or did he cause the deaths of his men because he was proud and vain, recklessly attacking a much larger force because he wanted the glory and credit of defeating the enemy before approaching reinforcements from General Terry and Colonel Gibbon could arrive?

The following two 1800s newspaper articles give an indication of how a shocked America learned the news of Custer’s annihilation, just days after the nation had jubilantly celebrated its centennial on 4 July 1876. The first old news article is an editorial that, while acknowledging Custer’s bravery and touting his remarkable Civil War record, nonetheless calls him “not well balanced” and speaks of his “rashness.” The second historical news article presents some of the first news the outside world learned of the disaster, conveyed by a scout who arrived on the scene with Colonel Gibbon after the battle and surveyed the carnage on the battlefield.

This historical newspaper editorial states:

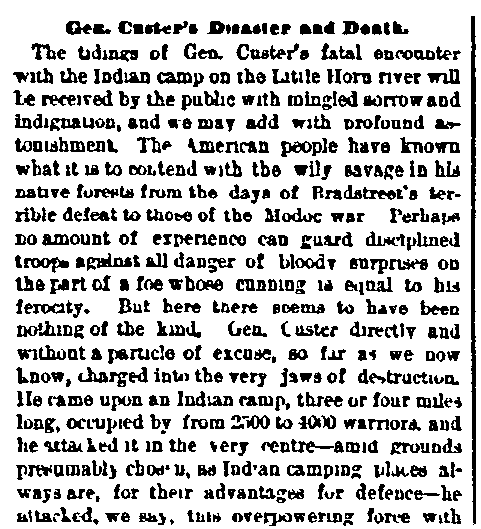

Gen. Custer’s Disaster and Death

The tidings of Gen. Custer’s fatal encounter with the Indian camp on the Little Horn River will be received by the public with mingled sorrow and indignation, and we may add with profound astonishment. The American people have known what it is to contend with the wily savage in his native forests from the days of Bradstreet’s terrible defeat to those of the Modoc war. Perhaps no amount of experience can guard disciplined troops against all danger of bloody surprises on the part of a foe whose cunning is equal to his ferocity. But here there seems to have been nothing of the kind. Gen. Custer directly and without a particle of excuse, so far as we now know, charged into the very jaws of destruction. He came upon an Indian camp, three or four miles long, occupied by from 2500 to 4000 warriors, and he attacked it in the very centre – amid grounds presumably chosen, as Indian camping places always are, for their advantages for defence – he attacked, we say, this overpowering force with 315 men! True, seven companies under General Reno were to make an attack in another quarter, and three companies were placed on a distant hill as a reserve, but these could render no assistance to Custer’s force, who, to a man, were simply butchered in cold blood! It is the most outrageous story that is yet on record in the annals of our regular army. We sincerely trust that some mitigating circumstances will come to light which will enable the American people to throw the mantle of charity over the fallen form of a brave officer who rendered some most excellent service in his time. Were he and his memory alone concerned we might say that he had paid the penalty of his rashness with his life, but the undeserved fate of his three hundred brave comrades who followed him to the slaughter, the bereavement of their families and the loss to their country, will not allow us to dismiss the matter thus lightly.

General George A. Custer, who, with two of his brothers and two other relatives, has thus fallen so suddenly and recklessly, was born in Ohio in 1840, so that he was only thirty-six years old at the time of his death. He graduated at West Point in 1861 and entered at once into active service in the war of the rebellion. He was in the Battle of Bull Run, in McClellan’s Peninsula campaign, in the battles of South Mountain and Antietam, in the Rappahannock campaign of 1863, in the battle of Gettysburg and the minor engagements connected therewith; he went through the whole of the Wilderness campaign and the Shenandoah campaign, and he bore a conspicuous part in the winding up operations at Five Forks and Appomattox Court House. It was a glorious career of service, and it raised its actor from Second Lieutenant of cavalry to brevet Major General. After the war Gen. Custer was put in command of the cavalry division of the Southwest and the Gulf, and in 1865-6 he was chief of cavalry in the Department of Texas. Since then he has been mainly on Western frontier duty.

Gen. Custer was preeminently the embodiment of the phrase, “a dashing cavalry officer.” His bravery was perfect, his energy was remarkable though not always sustained, and when under wise direction few officers were more effective and brilliant. But he was not well balanced, and Gen. Grant, whose judgment of army officers at least will never be questioned, deposed him from the chief command of the expedition against the Indians which has now so disastrously commenced operations. The act was largely attributed by a partisan press to personal and political prejudices, and Gen. Custer was ultimately allowed to go as commander of his regiment. It is of little use to bewail what is now past; we can only hope that Gen. Terry, who has the confidence of all, will retrieve the errors and fatalities which have thus far thrown a shadow over the expedition, and will bring it out successful in the end.

This article reports:

Custer’s Death

The Fearful Tale of an Army Scout

An Indian Camp of Two Thousand Lodges Attacked by the Troops

General Custer and His Command Perish to the Last Man

Three Hundred Soldiers Killed and Thirty-one Wounded

Seventeen Commissioned Officers Surrender Their Swords to Death

Salt Lake, July 5. – A special correspondent of the Helena (Montana) Herald writes from Stillwater, Montana, on July 2d:

Muggins Taylor, scout for General Gibbon, got there last night direct from Little Horn River. General Custer found the Indian camp, of about 2,000 lodges, on the Little Horn, and immediately attacked the camp. Custer took five companies and charged the thickest portion of the camp. Nothing is known of the operations of the detachment, only as they trace it by the dead. Major Reno commanded the other seven companies, and attacked the lower portion of the camp. The Indians poured in a murderous fire from all directions, besides the greater portion fought on horseback. Custer, his two brothers, nephew, and brother-in-law were all killed, and not one of his detachment escaped. Two hundred and seven men were buried in one place, and the killed are estimated at three hundred, with only thirty-one wounded. The Indians surrounded Reno’s command, and held him one day in the hills, cut off from water, until Gibbon’s command came in sight, when they broke camp in the night and left. The Seventh fought like tigers, and were overcome by mere brute force. The Indian loss can not be estimated, as they bore off and cached most of their killed. The remnant of the 7th Cavalry and Gibbon’s command are returning to the mouth of Little Horn, where a steamboat lies. The Indians got all the arms of the killed soldiers. There were seventeen commissioned officers killed. The whole Custer family died at the head of their columns. The exact loss is not known, as both the Adjutants and the Sergeant-Major were killed. The Indian camp was from three to four miles long, and was twenty miles up the Little Horn from its mouth. The Indians actually pulled men off their horses in some instances. I give this as Taylor told me, as he was over the field after the battle. The above is confirmed by other letters which say that Custer has met with a fearful disaster.

(Another account.)

Bozeman, Montana, July 3 – 7:00 P.M. – Mr. Taylor, bearer of dispatches from Little Horn to Fort Ellis, arrived this evening and reported the following:

The battle was fought on the 25th, thirty or forty miles below the Little Horn. Custer attacked the Indian village, from 2,500 to 4,000 warriors, on one side, and Col. Reno was to attack it on the other. Three companies were placed on a hill as a reserve. Gen. Custer and fifteen officers and every man belonging to the five companies were killed. Reno retreated under the protection of the reserve. The whole number of killed was 315. When General Gibbon joined Reno the Indians left. The battleground looked like a slaughter pen, as it really was, being in a narrow ravine. The dead were much mutilated. The situation now looks serious. Gen. Terry arrived at Gibbon’s camp on a steamboat, and crossed the command over and accompanied it to join Custer, who knew it was coming before the fight occurred. Lieut. Crittenden, son of Gen. Crittenden, was among the killed.

(The scene of this reported fight is near the Crow Indian Reservation. The correspondent of the Chicago Tribune, accompanying Gen. Crook’s expedition, writes on June 9 as follows.)

It is getting very monotonous in camp, and we use up a good portion of the time discussing the general plan of the campaign, and the whereabouts of the Sioux. The most generally-accepted opinion appears to be that all the Indians have left this part of the country, and are now on the Yellowstone, watching Gibbon, and skirmishing after Terry. Supporters of this theory base their opinion mainly on the fact that we have not been molested; that none of our camps have been fired into; and that our column, starting from Fetterman so long after Gibbon and Terry had taken the field, concentrated the vigilance of the savages on them alone, and consequently they are not yet aware of our invasion of their country, which, by the way, is not their country, but “Absaroka,” or the country of the Crows, from which tribe the Sioux have taken it.

(If this reported engagement [i.e., Custer’s fight] should prove true, it would seem to prove the correctness of the correspondent’s opinion, as the Indian camp is represented as being immense in size, and was pitched on the land of the Crow Reservation.)

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Related Articles: