Introduction: In this article, James Pylant concludes his story of the puzzling kidnapping of a young mother in Hollywood in 1921 that confounded the police. James is an editor at GenealogyMagazine.com and author for JacobusBooks.com, is an award-winning historical true-crime writer, and authorized celebrity biographer.

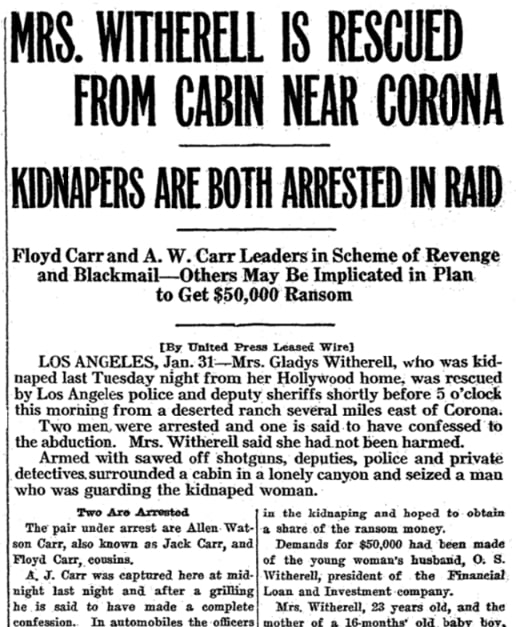

On 25 January 1921, 27-year-old Gladys Witherell was lured from her Hollywood home by a mysterious gray-haired man (see Part 1) telling a false story about a nearby automobile accident that she thought involved her mother-in-law.

When kidnapping suspects Charles Beverly and Leda Tenney were killed in a car crash while being tailed by detectives in the early morning hours of January 29, John C. Kratz feared his abducted daughter would never be found alive.

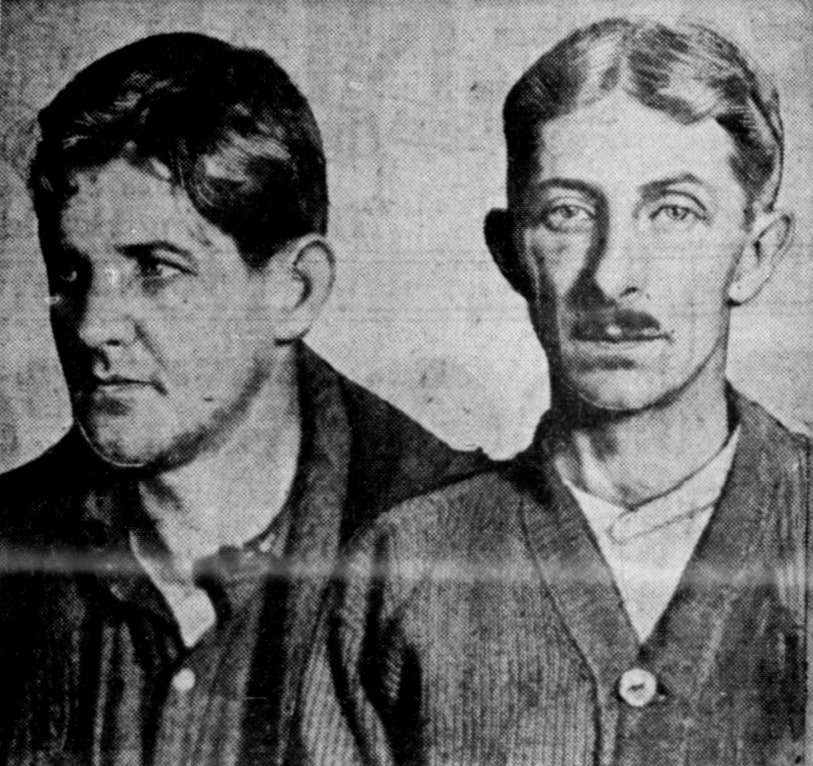

Yet, the investigation swiftly took a different direction later that same day, involving cousins Arthur (left) and Floyd Carr.

At 10:23 p.m. on January 29, Gladys’s husband Otto Witherell answered a phone call from a man identifying himself only as “O. S.” As the caller talked, telephone operator Alma Bryant eavesdropped on the conversation (as authorities had instructed her to do). As soon as she realized it was the kidnapper, she alerted three coworkers who tracked the call. Detectives had coached Otto that if the kidnapper happened to call, he should prolong the phone conversation as long as possible. That allowed operators to trace the call to a pay phone in Los Angeles.

The $2,000 reward was split among the four telephone operators who tipped the police about the caller.

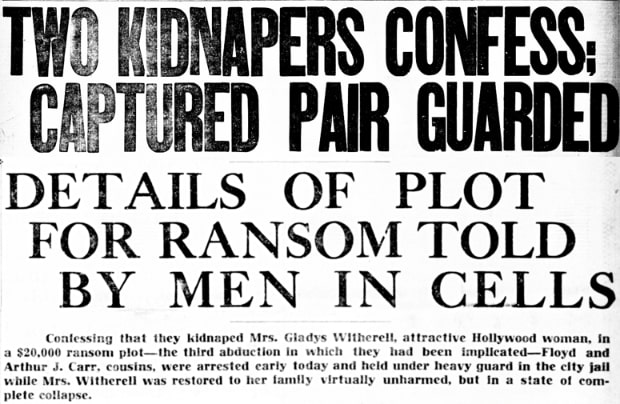

A five-car posse quickly surrounded the telephone booth just as Arthur Carr exited it, and police apprehended him. At the police station, he claimed to take orders from a crime syndicate, which investigators didn’t believe. They demanded he tell the truth, and after a barrage of questions, Carr admitted he knew Gladys’s whereabouts.

Based on Carr’s information, a posse arrived at a desolate canyon cabin near Corona, California, at 4:30 a.m. on January 31, where they rescued the kidnapping victim. Floyd Carr, the gray-haired stranger, was found hiding in a closet, brandishing a revolver. He was overpowered after a fierce struggle in the dimly lit cabin.

Arthur Carr stated the abduction was Floyd Carr’s revenge plot against Gladys’s father-in-law, A. J. Witherell. “You see, the old fellow had blocked him in a deal where he could have gotten a fishing yacht,” Arthur explained. “So, we decided to make him suffer a little bit.”

“We knew the Witherells had money and thought it would be easy to get $20,000 [down from the original demand of $50,000] by kidnaping the young woman,” Arthur told officers.

Later that day, the Carrs pleaded guilty to a charge of kidnapping in Los Angeles Superior Court.

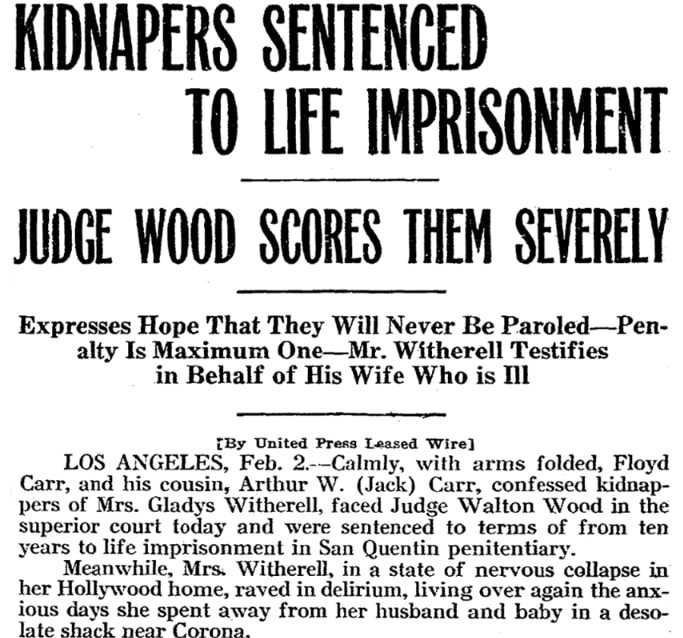

Otto appeared in court the next day and testified on behalf of his bedridden wife.

“These men many times discussed openly with her, the risk they were taking,” he said. “They scoffed at the law, scoffed at the penalty they might be forced to pay for their crime. They said the big money they would get if successful was well worth the chance of a few years in prison.”

But if the cousins thought the criminal justice system was going to let them off lightly, they were severely corrected by Judge Walton Wood during their sentencing on February 2.

This article reports:

“I know of no offense more despicable than the one you pleaded guilty to, even capital offenses,” remarked the judge. “There is a parole board but it usually consults the judge who passes sentence before it acts. I hope I am a judge 10 years from now when you two appear before the board.”

California’s state parole board denied the kidnapping Carrs’ release requests in 1936 and 1939. “No further consideration will be given the Carrs’ pleas for release, under the board’s ruling,” came with the second rejection.

As it turned out, the kidnapping of Gladys Witherell was unrelated to the brazen burglaries that alarmed Los Angeles in late 1920 and early 1921. A year after her abduction, several of the stolen items from that string of burglaries were sold, leading to the arrest of 79-year-old John Albert Burke who confessed to the thefts. Burke said that his banditry behavior came after being hit on the head with a gas pipe, which fractured his skull and caused headaches. He started drinking to ease the pain.

Claiming to be a blue-blooded Kentuckian, an Oberlin College graduate, and a Civil War veteran, Burke had become a prominent civil engineer and helped lay the path for the Denver-Rio Grande railway through Utah. In 1914, Burke was confined in an asylum in Santa Clara, California. He was working as a gardener at A. J. and Mary Witherell’s Hollywood house when he began burglarizing and stole $16,000 worth of furs and clothing from them.

He claimed to have asked a physician to write a letter to the Witherells to explain that Burke’s physical trauma led to amnesia, which caused him to “do things of which he had no recollection later.” Burke was given a five-year probationary sentence considering his “past usefulness and advanced years.”

After their two ordeals (the robbing of Otto’s parents’ house, and the kidnapping of his wife Gladys), the younger Witherells kept a low profile. In the 1930s they relocated to Chicago, where Otto was vice president of a manufacturing company.

In 1948, Gladys’s 81-year-old father, John C. Kratz, was killed when the car in which he was a passenger plunged over a 150-foot embankment in Redlands, California.*

Otto died in 1967. Gladys survived him by 19 years, dying in 1986. Both were interred in a Hollywood mausoleum. Their son, John Allen Witherell, died in 1995.

* “Two Local Men Killed in Crash,” Anaheim Bulletin (Anaheim, California), 24 January 1948, p. 1

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: Sherlock Holmes investigates a mystery.

Illustration credit: https://depositphotos.com/home.html

Related Article: