Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry continues her series on descendants of the Jamestown settlers, writing more about the French ancestor of George Washington. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Today I continue with my “Jamestown Descendants: Who’s Who” series, again focusing on General George Washington – whose ancestors included English noblemen and one French Huguenot who came to Jamestown, Virginia.

To recap: my last story covered Washington’s ancestor Nicolas Marteau (note the spelling is generally accepted as Martiau), a French Huguenot who came to Virginia in 1620 on the ship Frances Bona Venture. (See: Jamestown Descendants: Who’s Who, Part 5)

I found an interesting article published in the Milwaukee Journal in 1929, written by Frank and Cortelle Hutchins, noted Virginia historians whose ancestors were part of the Virginia Company.

This article’s title and subtitle succinctly tell the tale:

Washington’s Ancestry Was Part French

Even the General Knew Nothing of the Dashing Young Cavalier Who Was His First Forefather in America and Who Won from the Wilderness the Very Land on Which His Illustrious Descendant Was to Fight the Battle of Yorktown

Washington’s French ancestor was destined to lead the first American rebellion against British tyranny, nearly 150 years before the American Revolution.

As noted by the Hutchins, upon arrival Martiau became an established figure in Jamestown Colony.

He married Jane, widow of Lt. Edward Berkeley, in the spring of 1627. (Their first-born daughter, Elizabeth Martiau, married George Reade – Washington’s gr. great grandparents.) Nicolas Martiau acclimated into the role as a perfect Englishman: English home, English honors, and now an English wife.

But alas his soul was French, and his tongue sometimes forgot that it was naturalized. Here comes the drama…

There is a rebel tale recorded in 1627 by Ensign George Thompson, who was out on a boat scouting with Thomas Mayhew and Martiau.

The two Englishmen struck up a conversation about the King of England, who they asserted was also king of Scotland, France, and Ireland.

This angered Martiau, who insisted that the king who sits on the throne in France is French born and not the King of England.

Martiau then put his hand upon his breast and asserted: “Though I am here yet this sparke is in France and will not here the King wronged.”

The hasty words were treasonous and landed Martiau in front of the Governor and council. He was not punished but was ordered to take the oath of loyalty to Jamestown.

By 1630 Martiau was granted 1,300 acres known as Kiskyake. As the Hutchins wrote:

“Upon its sightliest bluff was some day to stand Yorktown; and there Gen. George Washington was to come and win a great victory – never knowing that he ended the American Revolution upon his French grandfather’s plantation.”

A few years after Martiau was granted his plantation, the land was divided into a new borough known as York. Sir John Harvey, the royal governor of Virginia, named Martiau one of the justices of York County.

Today there is a plaque marking the site of where the home of Nicolas Martiau stood, at the intersection of Ballard Street (Virginia Route 1020) and Main Street, Yorktown, Virginia. The plaque reads:

“Site of the home of Nicolas Martiau, the adventurous Huguenot who was born in France 1591, came to Virginia 1620 and died at Yorktown 1657. He was a captain in the Indian uprising, a member of the House of Burgesses, Justice of the County of York. In 1635 a leader in the thrusting out of Governor Harvey, which was the first opposition to the British colonial policy. The patentee for Yorktown, and through the marriage of his daughter Elizabeth to Col. George Reade, he became the earliest American ancestor of both General George Washington and Governor Thomas Nelson. Marked by the Huguenot Society of Pennsylvania in cooperation with the National Federation of Huguenot Societies and the Yorktown Sesqui-centennial Commission 1931.”

By 1635 Martiau reached the height of his career, and had become important enough to be a revolutionary who would lead America’s first uprising against royal oppression.

Martiau’s fiery spirit resented the arrogance of Sir John Harvey and led him to one of the most important roles he would play. More drama awaits…

Here is the skinny according to the Hutchins account:

Now an unworthy man set [sat] in the great velvet chair as governor of Virginia – Sir John Harvey. Overproud, arrogant, he strutted in gold laced finery about little Jamestown. A contemptuous smile for even the members of council. He sought to make laws all by himself, and suppressed petitions from the colonists to the crown.

Indignation and resentment smoldered along the James [River]; almost flamed along the York [River].

On a late April evening, two or three men, seemingly strangers on the York, appeared at the house of William Warren, Marteau’s neighbor down river.

They were refused admittance but stayed close enough to eavesdrop. There was a meeting going on involving men angry at Harvey’s authoritarian manner.

Listening ears identified several prominent men among the speakers, especially the leader Justice Nicolas Marteau. By the time he had finished speaking, the eavesdroppers scented treason, and took off through the black forest for Jamestown. It was far into the night before they reached Harvey with the story of the “mutenye.”

His action was prompt and drastic. Next morning Capt. Marteau and two or three others were arrested, carried to Jamestown, given over to a brutal keeper and, by Harvey’s order, placed in irons. When they would have the reason for all this, they were told they “should know at the gallows.”

Now the governor summoned the council to his own home. Memorable meeting. Harvey strode in anger up and down the room, virtually demanding the prisoners’ instant death. He found himself facing cold, unresponsive men. He stormed his demand. They coolly said no. Was it treason again? Premeditated, too? For, as the wrathful governor looked about, he saw that each of these councilors he had meant to bend to his will sat there armed.

But Sir John Harvey was at least no coward. Advancing to one of leading members, he struck him heavily on the shoulder, declaring, “I arrest you, sir, upon suspicion of treason!”

Suddenly cold councilors flamed hot enough. They crowded angrily about the representative of the king. One seized him roughly, exclaiming, “And we the like to you, sir!”

Forced into a chair, Harvey sat helpless. Then a signal was made at the window, and in an instant the house was surrounded by armed men. The royal governor of Virginia was a prisoner.

Stay tuned!

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in.

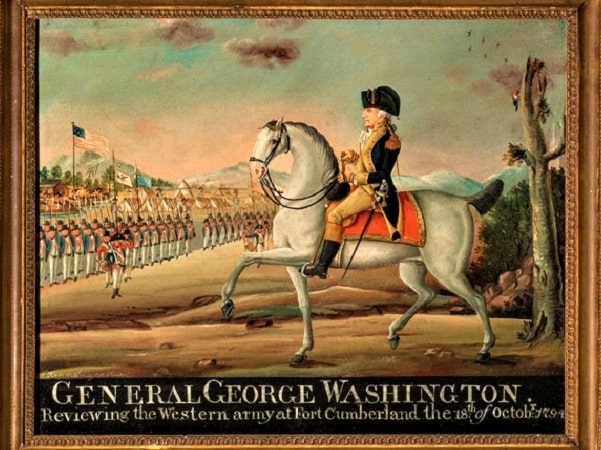

Note on the header image: “General George Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, the 18th of October 1794.” Artist: Frederick Kemmelmeyr. Bequest of Henry Francis du Pont. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Winterthur, Delaware.

Related Articles: