With cell phones a global phenomenon, it seems like almost everyone is talking on the telephone these days. Phones are now an essential component of modern life, enabling conversations and keeping us connected to the world by providing Internet access. We use telephones to look up information, send text messages, take pictures, record videos, and play music, movies and games.

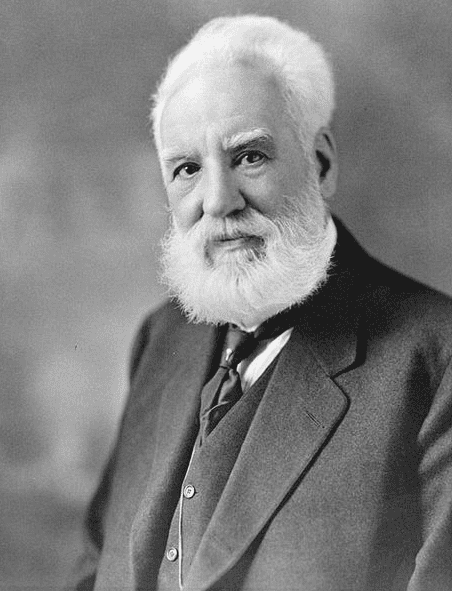

Yet, as with everything else, there had to be a first time – a magical, almost miraculous moment when eyes filled with wonder as the listener heard the voice of someone talking from another location. That incredible moment happened on 10 March 1876, when Alexander Graham Bell spoke the famous words “Mr. Watson, come here; I want to see you” into a transmitter and his assistant, Thomas A. Watson, heard the words clearly in another room.

The truth is there was no single inventor of the telephone. In addition to Bell, a number of great minds worked hard on the concept and contributed to the marvel we call the telephone, including Thomas Edison, Elisha Gray, Innocenzo Manzetti, Antonio Meucci, and Johann Philipp Reis.

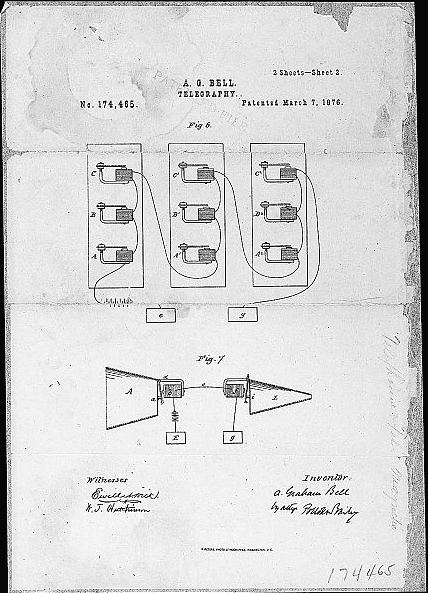

Alexander Graham Bell was granted the first patent for the telephone, number 174,465, issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office on 7 March 1876.

Three days later Bell made his famous successful phone call to Watson. Other inventors, especially Antonio Meucci and Johann Philipp Reis, made earlier claims of successful sound transmissions, but Bell’s March 10 sentence to Watson is credited as the first clearly spoken and understood phone conversation.

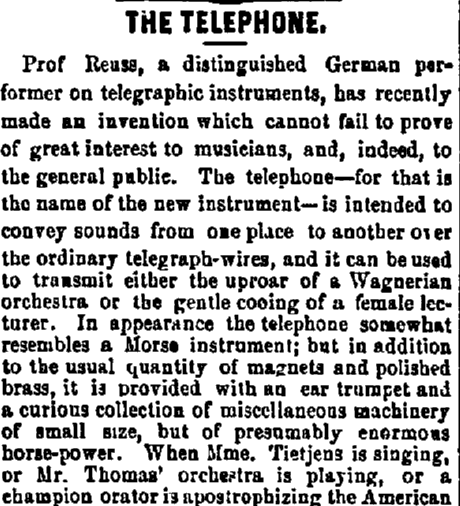

Imagine trying to describe the wonder of a telephone to a world that had never known one before. The reporter in this 1876 newspaper article does just that. Though he mentions Reis, he could just as easily be speaking of Bell. The point is, what he’s really trying to express is just how much the telephone is going to change the world.

The following article was originally published by the New York Times and reprinted by the Baltimore Bulletin on 8 April 1876.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Prof. Reuss [i.e., Reis], a distinguished German performer on telegraphic instruments, has recently made an invention which cannot fail to prove of great interest to musicians, and, indeed, to the general public. The telephone – for that is the name of the new instrument – is intended to convey sounds from one place to another over the ordinary telegraph wires, and it can be used to transmit either the uproar of a Wagnerian orchestra or the gentle cooing of a female lecturer. In appearance the telephone somewhat resembles a Morse instrument; but in addition to the usual quantity of magnets and polished brass, it is provided with an ear trumpet and a curious collection of miscellaneous machinery of small size, but of presumably enormous horse-power. When Mme. Tietjens is singing, or Mr. Thomas’ orchestra is playing, or a champion orator is apostrophizing the American eagle, a telephone, placed in the building where such sounds are in process of production, will convey them over the telegraph wires to the remotest corners of the earth. By means of this remarkable instrument, a man can have the Italian opera, the Federal Congress, and his favorite preacher laid on in his own house. Before many years we shall probably read in the advertisements of house agents’ descriptions of houses to let in which hot and cold water and Baptist preachers are laid on in every room; of others fitted throughout with gas and Congressional orators; and still others in which the front parlor is telephonically connected with the Academy of Music, and the back parlor contains a series of instruments by means of which fifty eminent preachers, of different denominations, can be kept constantly on draught.

The universal use of the telephone will, of course, be viewed with disapprobation by the sound-producing part of the community, just as the introduction of labor-saving machines was met by the hostility of the laboring classes. No man who can sit in his own study with his telephone by his side, and thus listen to the performance of an opera at the Academy, will care to go to Fourteenth street and to spend the evening in a hot and crowded building. In like manner, many persons will prefer to hear lectures and sermons in the comfort and privacy of their own rooms, rather than to go to the church or lecture-room. The rural visitor who spends a Sunday in town, and reads a printed notice in the office of his hotel to the effect that “Talmage’s sermons, drawn from the wood, can be had at 11 o’clock in the telephonic room,” will, of course, give up his original intention of risking a journey to Brooklyn, and will listen to the trembling telephone as its sympathetic brass vibrates to the tones of the resonant Brooklyn orator. Thus the telephone, by bringing music and ministers into every home, will empty the concert halls and the churches, and the time may come when a future Von Bulow playing a solitary piano in his private room, and a future Talmage preaching in his private gymnasium, may be heard in every well-furnished house on the American continent.

Related Articles: