Introduction: In this article, particularly relevant in light of the current Coronavirus pandemic, Jane Hampton Cook searches old newspapers to learn more about the Yellow Fever Epidemic that devastated Philadelphia in 1793. Jane, the former White House webmaster for President George W. Bush, is a presidential historian and the author of nine historical books. She is a consultant for the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission. Her works can be found at janecook.com.

As America combats the novel coronavirus, looking back at America’s first epidemic during George Washington’s presidency – using GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives – shows how Alexander Hamilton used the power of the press to try to save lives.

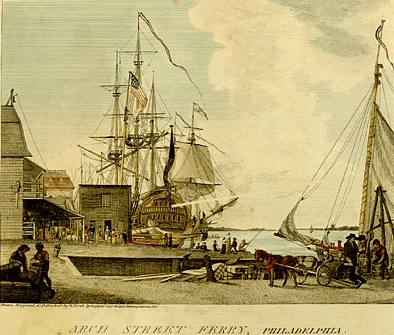

Yellow fever cases began in early August 1793 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, soon after a ship arrived from Santo Domingo, which had experienced a previous outbreak.

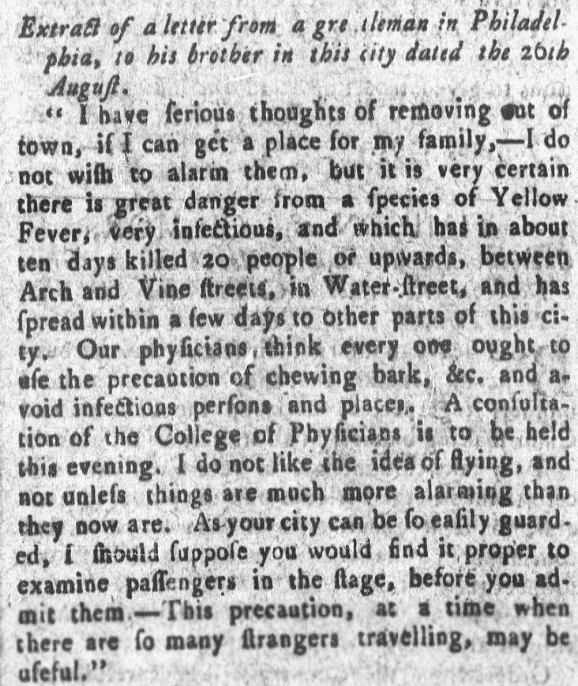

At the end of August, New York’s Weekly Museum published a letter from Philadelphia (at that time, the capital of the United States):

“…it is very certain there is great danger from a species of Yellow Fever, very infectious, and which has in about ten days killed 20 people or upwards, between Arch and Vine streets, in Water street, and has spread within a few days to other parts of this city. Our physicians think every one ought to use the precaution of chewing bark, &c., and avoid infectious persons and places.”

When Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton came down with yellow fever in Philadelphia, Hamilton used the power of the press to try to save lives.

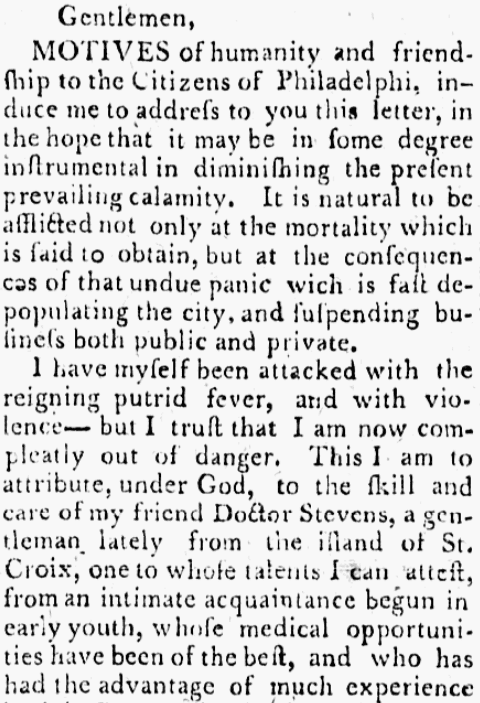

Worried about the “…undue panic which is fast depopulating the city, and suspending business both public and private,” Hamilton wrote a letter on 11 September 1793 to Philadelphia’s College of Physicians.

Hamilton’s letter was published in the Daily Advertiser and other newspapers. He had battled the disease’s yellowing of the skin, high fever, and stomach bleeding that led to black vomit:

“I have myself been attacked with the reigning putrid fever, and with violence – but I trust that I am now completely out of danger. This I am to attribute, under God, to the skill and care of my friend Doctor Stevens, a gentleman lately from the island of St. Croix.”

Hamilton met Stevens when he was a child in the Caribbean, where yellow fever was common. In his published letter, he recommended Stevens’ treatment method:

“His mode of treating the disorder varies essentially from that which has been generally practiced – And I am persuaded, where pursued, reduces it to one of little more than ordinary hazard.

“I know him so well, that I entertain no doubt, that he will freely impart his ideas to you, collectively or individually, and being in my own person a witness to the efficacy of his plan, I venture to believe, that if adopted, and if the courage of the citizens can be roused, many lives will be saved, and much ill prevented.”

Stevens’ method involved taking baths, drinking wine and inhaling herbs.

Hamilton knew that Stevens opposed the common blood-purging method and other remedies of Benjamin Rush, the city’s most prominent physician. Given what we now know about medicine, allowing leeches to suck blood from a patient did not purge poison and was actually harmful. Stevens’ method reflects today’s hygienic and homeopathic approaches.

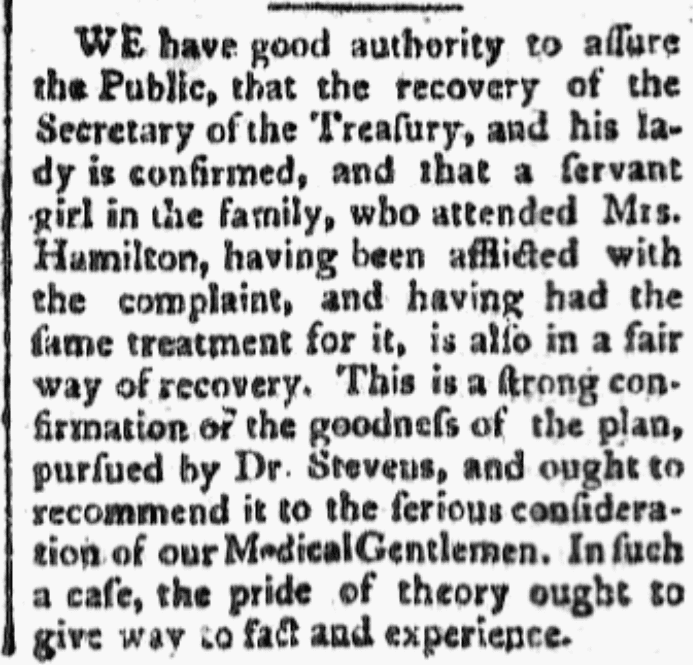

The Independent Chronicle reported:

“We have good authority to assure the Public, that the recovery of the Secretary of the Treasury, and his lady, is confirmed.”

The article noted that one of the Hamilton’s servants had also gotten sick, followed the same protocol, and had recovered, concluding:

“This is a strong confirmation of the goodness of the plan, pursued by Doctor Stevens, and ought to recommend it to the serious consideration of our Medical Gentlemen. In such a case, the pride of theory ought to give way to fact and experience.”

In Philadelphia, a city of 50,000 people, yellow fever took more than 5,000 lives in 1793. As I wrote about in my book The Burning of the White House, among the victims was John Todd. His wife Dolley married Congressman Madison nearly a year later – 15 years before James Madison became the nation’s fourth president in 1809.

What ended the 1793 yellow fever epidemic? Winter. Cooler temperatures killed the mosquitoes that spread the disease. A U.S. Army physician discovered that mosquitos spread the disease in 1900.

Related Article:

This was excellent! The power of the press and herbal remedies! Right on!

So fascinating!! Thank you!!

I so so agree. The power of the Press. I saw recently in a old newspaper about the danger of ships entering NZ ports with no railings and a couple of kids falling in, etc. A gentleman (can’t remember his name now, shame on me) — but anyway, the Port Master never did anything about it until this guy went to the press. Twice he approached them and finally the Port Master and/or Council (late 1800s) put safety rails in. Gather he didn’t like the negative publicity.

May not be about the epidemic in this article or about today’s pandemic, but it reminds us of the importance and power of the the Press, in that time and now in our time. As long as it serves us with honesty and integrity, with relevant information, the Press is here to stay.

I also include the latest version of the Press, i.e., The Internet.

Oh yeah — and the power of herbal remedies.