Introduction: In this article, Mary Harrell-Sesniak writes about resources and techniques to help you find family history information in foreign-language newspapers, even if you’re not familiar with that language. Mary is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background.

GenealogyBank’s recent announcement that it is adding Italian American newspapers in 2013 is a welcome addition—but it may also concern family history researchers who are nervous about navigating foreign languages.

However, there are certain resources and techniques you can use to find valuable genealogical information in foreign-language newspapers, even if you have limited—or no—familiarity with the language, as this article explains.

My roots include a number of German immigrants who settled in various parts of Pennsylvania. By using specific techniques, I have been able to locate information about these ancestors from the German American newspapers in GenealogyBank’s online historical newspaper archives.

Some of these German-language newspapers include:

- Cincinnati Volksfreund (Cincinnati, Ohio)

- Der Wahre Amerikaner (Lancaster, Pennsylvania)

- Der Zeitgeist (Egg Harbor City, New Jersey)

- Deutsche Porcupein (Lancaster, Pennsylvania)

- Egg Harbor Pilot (Egg Harbor City, New Jersey)

- Highland Union (Highland, Illinois)

- New Jersey Deutsche Zeitung (Newark, New Jersey)

- Nordwestliche Post (Sunbury, Pennsylvania)

- Reading Adler (Reading, Pennsylvania)

- New Yorker Volkszeitung (New York, New York)

- Northumberland Republicaner (Sunbury, Pennsylvania)

- Unparteyische Harrisburg Morgenroethe Zeitung (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania)

When presented with a language hurdle in your genealogy research, try not to be intimidated.

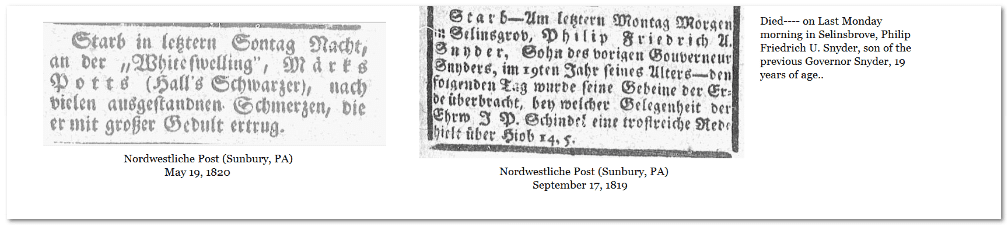

By employing a free language translator such as Google Translate and consulting foreign genealogical word lists, you may be able to determine the gist of a notice, such as the two death notices shown in the following illustration. They report that the decedents died (“starb”) on last Sunday night (“Sontag Nacht”), and on last Monday morning (“Montag Morgen”), respectively.

Some of my family’s notices were published in the Reading Adler (Reading, Pennsylvania), which published alternately in both English and German.

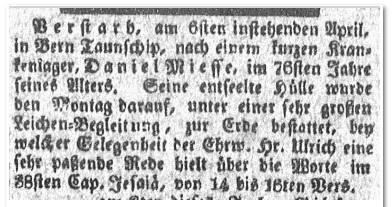

This particular German-language obituary relates to my ancestor Daniel Miesse (28 January 1743, Elsoff, Germany to 1 April 1818, Berks County, Pennsylvania), who died in Bern Township in the 76th year of his age.

An interesting explanation of the interchangeability of Germanic letters can be found in Family Search’s German Word List.

Its explanation notes that “spelling rules were not standardized in earlier centuries,” so variations are common. It is best to substitute letters, if you cannot make a definitive translation, or to do a reverse look-up by querying obvious terms. For example, choose a word in English that you might assume to be in a foreign notice. Then, translate it into your target language (e.g., German).

This blog article would not be complete without noting that search engines are often type-face-challenged; being persistent and varying your queries is central to finding ancestral notices in foreign-language newspapers.

While researching my genealogy, I sometimes query with German terms whose meanings I have learned over the years: “taufe” or “taufen” helps locate christenings; “heiraten” finds marriages; and husband or wife can be found by searching on the terms “mann,” “ehermann” and “gatte,” or “ehegattin,” “frau” and “gattin.”

Generally, search software does a fine job in responding to queries, by employing sophisticated “optical character recognition” (OCR) techniques—which is the process by which the computer makes an electronic conversion of scanned images.

However, it sometimes does not produce the desired results. Reasons vary, but foreign publications often used different type styles, such as German Fraktur, Blackletter and Gothic type, and foreign languages may include letters of the alphabet which do not exist in English.

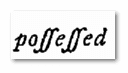

And even old English presents a unique situation—since archaic spellings changed over time. The classic example is the interchangeable use of ff and ss, as seen in this 18th century spelling of possessed.

Hopefully, by employing these techniques, you will be able to successfully navigate a variety of foreign-language newspapers. Don’t be intimidated! Plunge right in—you may be agreeably surprised by what you find out about your family history.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

I also found that sometimes the names are different too. My Great grandfather Here in USA his name is Charles, in Germany it is Carl. I found this by looking at marriage records. I knew Charles Married Caroline in Germany in 1856. Know that my Charles was born in 1830 and her in 1934 I did find out that his name in Germany is Carl… I now know that you have to be part detective to do some family searching….