Introduction: In this article, Jane Hampton Cook describes when and how newspapers started using the term “White House” for the president’s house. Jane is a presidential historian and author of ten books, including her new book “Resilience on Parade: Short Stories of Suffragists & Women’s Battle for the Vote.” She is the author of “Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War.” She was the first female White House webmaster (2001-03). Her works can be found at Janecook.com.

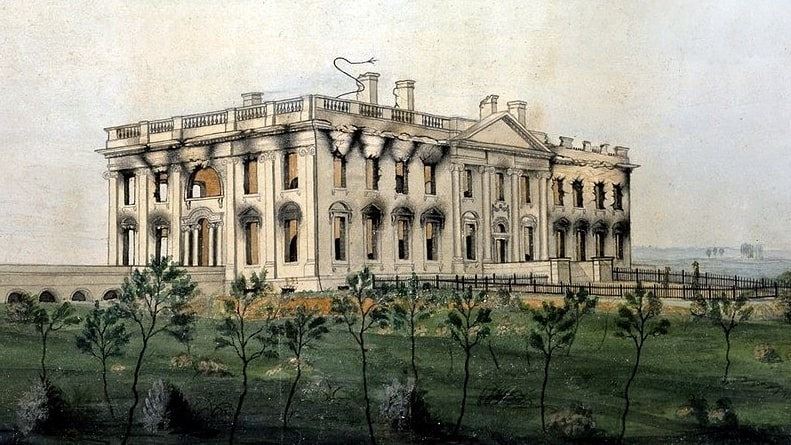

For years, the origin of the name “White House” was unknown. Some thought the term was first used when it was rebuilt in 1817 and painted white after the British military burned it in 1814.

George Munger, 1814-1815. Credit: The White House Historical Association; Wikimedia Commons.

Now, thanks to the digitization of newspapers such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, we can see that the term White House was first used in a negative way in newspapers years before the British attack.

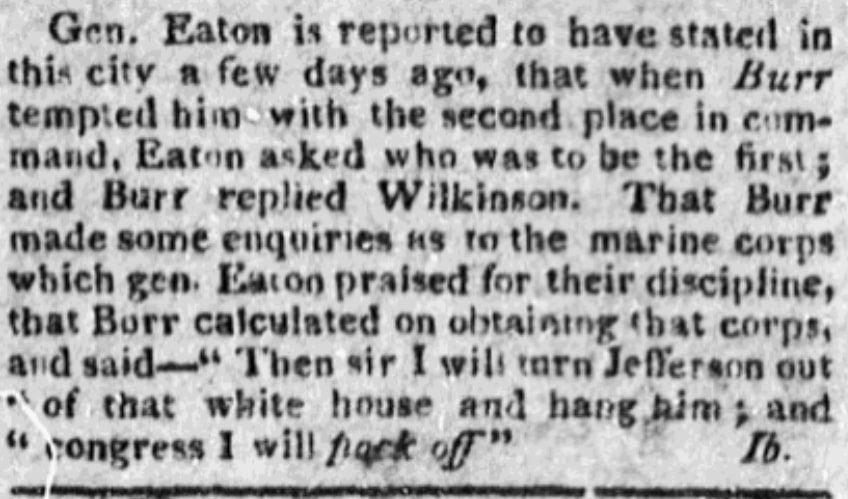

Vice-President Aaron Burr used the term in reference to President Thomas Jefferson in 1807.

“Then sir I will turn Jefferson out of that white house and hang him; and Congress I will pack off,’” Vice President Aaron Burr bitterly told a general, as New York’s Republican Watch-Tower reported.

This was one of the first – if not the first – newspaper references using the term “white house.”

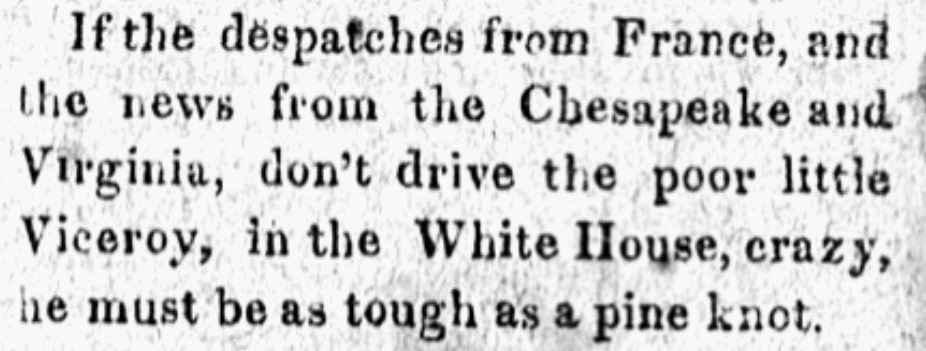

The phrase White House was also used to attack Jefferson’s successor, President James Madison.

“If the despatches from France, and the news from the Chesapeake and Virginia, don’t drive the poor little viceroy in the White House crazy, he must be as tough as a pine knot,” reported the Federal Republican in 1813.

Here is another example of the phrase being used before the British burned the White House in 1814.

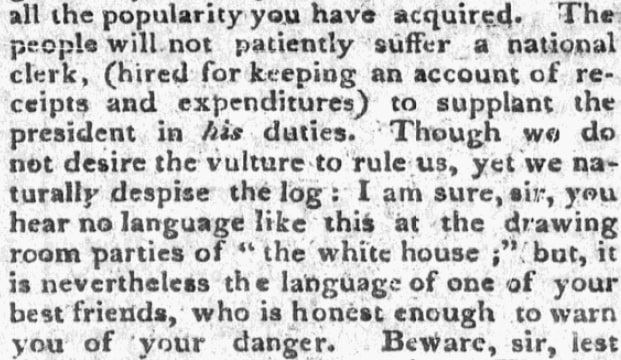

“You hear no language like this at the drawing room parties of ‘the white house,’” the Alexandria Daily Gazette, Commercial & Political said disparagingly in 1810.

With the term being used with so much animosity, how did “White House” become a term of endearment? Though it’s impossible to know for sure, a party hosted during the holiday season appears to be the start of turning a slur into a salute of pride.

December was the traditional kickoff of Washington, D.C.’s social season, which was an outgrowth of Congress beginning a new session. In December 1813, President James Madison’s wife Dolley (the term “First Lady” wasn’t used until much later) set the White House ablaze with a glow and merriment that caught the eye of an influential Philadelphia reporter visiting the nation’s capital.

“I must not forget, however, to mention that Mrs. Madison, the President’s Lady, gives a tea party every Wednesday evening,” Tyro reported for the Democratic Press about the party he attended on 15 December 1813. Most intriguing to him was the openness of the occasion. Anyone could attend. That meant him.

“It was a novelty to me to find that these parties were not assembled by cards of invitation, but that every body was free to appear there, and that all were received with hospitality, politeness, and attention. Finding access so easy, I wished to attend last Wednesday evening.”

Coffee. Cakes. Nuts. Fruit. Whiskey Punch. Much tempted him. “Refreshments were very liberally handed round, and all partook freely and cheerfully. I understood it was a pretty full assembly: there might have been from one to two hundred persons present of both sexes.”

He went on to say:

“The President, Mr. Madison, mixed with the company all the evening, and talked by times with every body; even I claimed some notice where I looked for nothing but a common salutation.”

What was also novel about these parties was that members of both political parties attended, which had not been the case during Jefferson’s administration.

Tyro told his readers that “the men who slander him [Madison] with the most reprobate license seek his hospitality.” Dolley’s charisma was a huge factor in making everyone feel welcome.

From the food to the openness, to the bipartisanship and the frivolity, this December party during the holiday season left a strong impression.

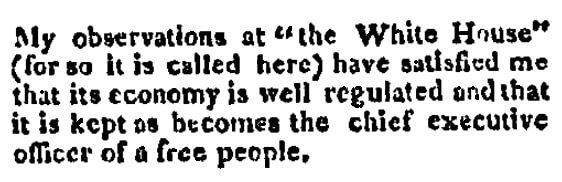

“My observations at ‘the White House’ (for so it is called here) have satisfied me that its economy is well regulated and that it is kept as becomes the chief executive officer of a free people,” Tyro concluded.

This appears to be the first positive use of the phrase White House in a newspaper. Dolley and James Madison’s hospitality during the holiday season made all the difference.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Wonderful article on the history of the “White House” — please keep them coming. Regards, Scott

I’ve wondered at times where the name “White House” orginated from; thank you for this article.

Interesting article.