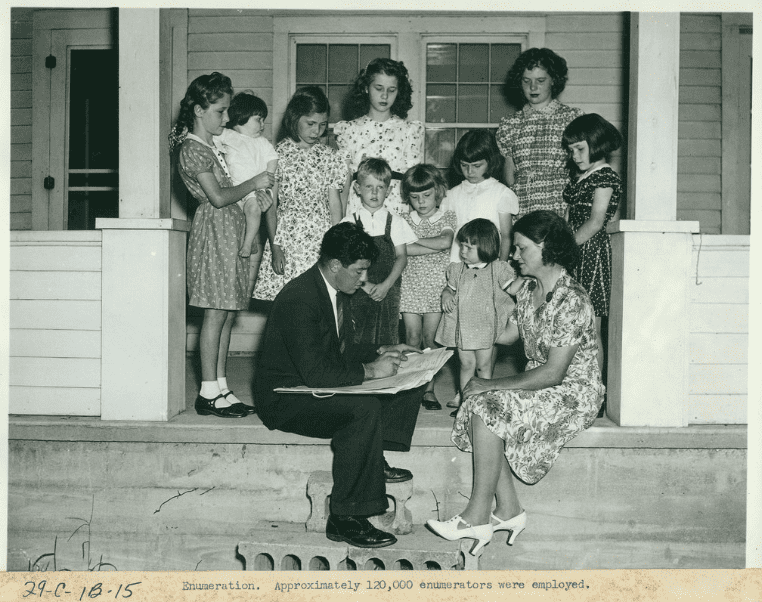

Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega writes about the 1940 U.S. Census – the latest census year available to the public. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

The 1940 census records. Most likely you are very familiar with this census since it is the latest census year available to the public. Maybe you even remember the day when it was released in 2012. There’s no doubt that the 1940 U.S. Census holds important information for those researching their more recent family history, including where their family lived on the census day in 1940 as well as on 1 April 1935.

The 1940 U.S. Census also asked extensive employment questions. This census takes into consideration the economics of the Great Depression and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program, and asks questions about “participation in the New Deal Civil Conservation Corps, Works Progress Administration, and national Youth Administration.” (1)

How much do you know about the 1940 U.S. Census? Here are a few things to consider as you take a look at this important resource for family history research.

Lies I Told the Census Enumerator

Most experienced genealogists will tell you that census information may not be reliable for all sorts of reasons. For example, the census enumerator may have heard the answers to their questions incorrectly or mis-transcribed them. The person providing the information to the enumerator may have lied or at least fudged the truth a little for all kinds of reasons – from wanting to appear younger than they really were, to the belief that the government didn’t have the right to know their business.

What’s a census taker to do? The census enumerator instructions explain what to do in cases where someone refuses to cooperate. Aside from explaining that the information they were providing was for statistical use only and confidential, enumerators were reminded that they were “forbidden to communicate to any person who is not a sworn census employee any information obtained by you in the discharge of your official duties.” A census worker who revealed confidential information risked paying a fine or spending time in jail.

But what if, even after promises of confidentiality, the enumerated still wouldn’t reveal the information asked of them? The census enumerator was instructed to write “Refused to answer” on the census sheet and report that to their supervisor. If the census enumerator thought the person was lying, they were instructed: “Do not accept any statement that you believe to be false. When you know that the answer is incorrect, enter upon the schedule the correct answer as nearly as you can ascertain it.” (2)

Asking the Questions

It’s obvious to us as researchers that not everyone enumerated in a household would be the best person to answer the questions posed. The Census Bureau knew that and gave enumerators instructions on whom to interview in each household:

“In order to obtain accurate and complete information, interview a responsible adult member of the household. Young children will usually be unable to give you the information desired for the Population schedule. Only occasionally will boarding or lodginghouse keepers be able to give you complete information concerning roomers or lodgers, and it is desirable, therefore, that as far as possible, you obtain information directly from roomers and lodgers. Likewise, boarders, lodgers, and servants will seldom be able to give the information concerning members of the household other than themselves. Obtain information about a household or a person from neighbors or other nonrelated persons only when it is impossible, after the second or third visit, to obtain the information through direct interview with a member of the household.” (3)

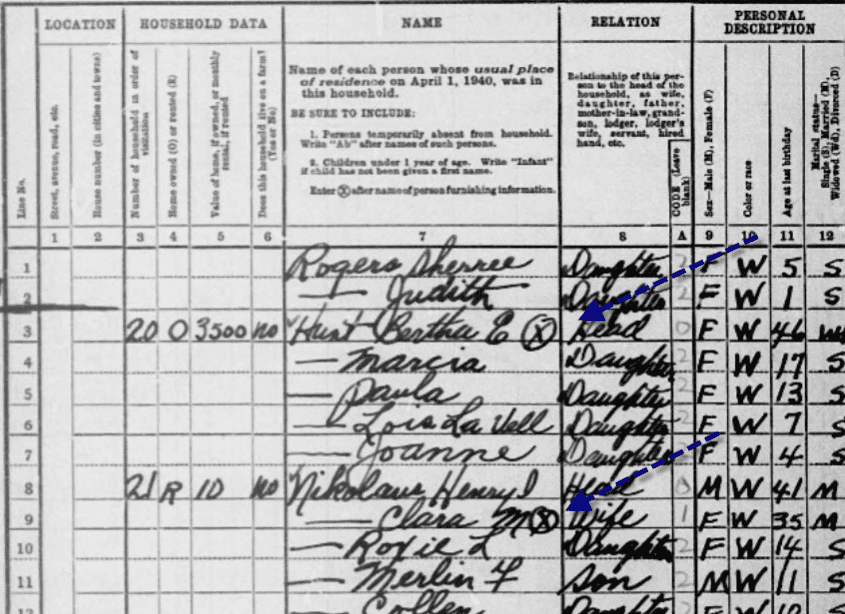

The 1940 census provides a piece of information that helps family historians determine how reliable the census data is for each family: enumerators were instructed to identify who the informant for each household was. Census enumerator instructions indicate that the informant should be identified with a “x” with a circle around it in column 7 after the name of the person furnishing the information. Why is this important? Prior to 1940, researchers have no idea who provided the information for each individual enumerated, so it’s even harder to determine the accuracy of the information on pre-1940 censuses.

Now what if no one in the household was able to provide the information to the enumerator and instead it was obtained from a neighbor or someone else? The name of the informant was to be written in the left-hand margin opposite the entries for the household. (4) In the case of a non-English speaking household, enumerators were encouraged to find a translator nearby, like a neighbor, or to try to fill it out the best they could with the respondent’s limited English. Paid interpreters were only to be used in “extreme cases.” (5)

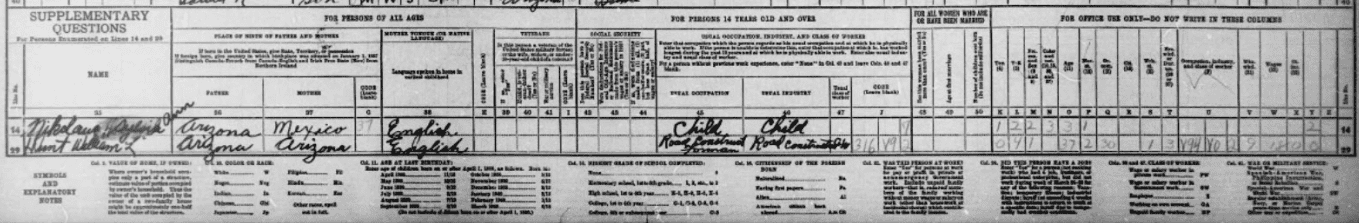

Did Your Ancestor Answer the Supplementary Questions?

If you’re lucky, you may find that your ancestor was asked the supplementary questions. These supplementary questions were asked of a small sample of those enumerated, for statistical purposes.

Because it is a random sample, some of the information – depending on who the enumerated was – could provide great information for the family historian, including:

- Parent’s birth place

- Native language spoken in earliest childhood

- Veteran information (whether the person was a veteran or the wife, widow or under-18-year-old child of a veteran, and either war or military service)

- Social Security (does the person have a Social Security number, whether deductions were taken from their salary in 1939 for “Old Age Insurance” or railroad retirement)

- Occupation (usual occupation and industry)

- Questions for women (married more than once, age at first marriage, number of children ever born)

A Few Tips

- The 1940 U.S. Census can lead you to many other records. Consider for example the Veteran supplementary questions (columns 39-41). The letter code in column 41 indicates if the veteran was a part of the World War (WWI); Spanish American War, Philippine Insurrection or Boxer Rebellion. This should lead the researcher to search for military and possibly pension records. As you note everything listed about your ancestral family, ask yourself what other records can help verify or provide more information, including historical newspapers such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives.

- Reminder: the US census records are now available on GenealogyBank.

- Read the census enumerator instructions. This will provide you with information on how the census was to be taken, identify abbreviations, and help you better understand what you are finding. You can find the 1940 census enumerator instructions on the U.S. Census website. The instructions include the abridged instructions and the Spanish-language instructions for Puerto Rico.

- If you are interested in learning more about the 1940 census, consider the online report “Procedural History of the 1940 Census of Population and Housing” prepared by the Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin (1983).

- If you prefer to transcribe the information you find on the census, the National Archives has a blank form you can download.

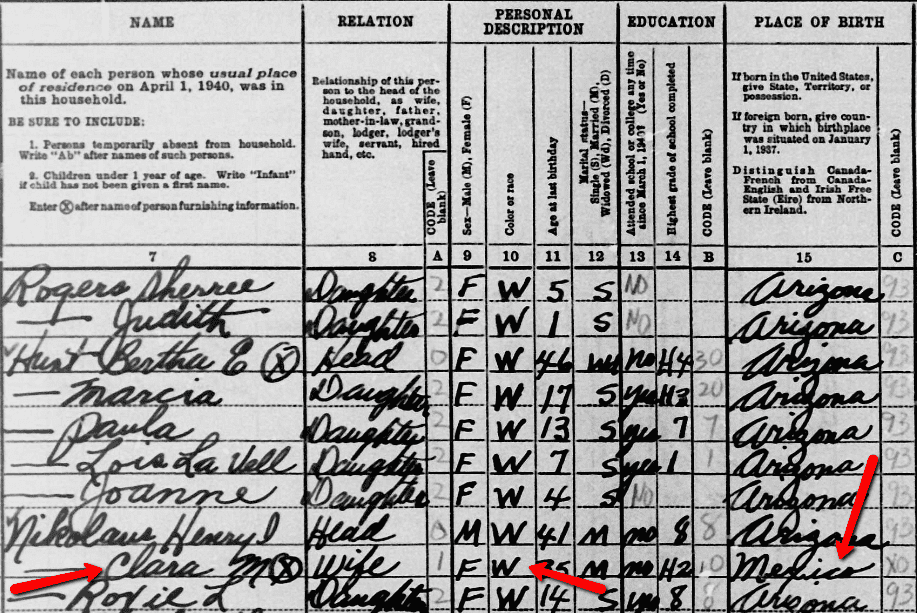

- Lastly, don’t make assumptions about what you find recorded on the census – an important reminder for any record you find. For example, in this entry for my maternal grandmother you notice that she (Clara Nikolaus) is listed as being white and born in Mexico.

This information is correct: her parents were both Anglo Americans who were living in Mexico at the time of her birth. But if she had been Hispanic, she would still have been described as white: “Mexicans are to be regarded as white unless definitely of Indian or other race.” (6) So, in some cases the census information is not specific enough and needs to be verified with other record sets.

_________________

(1) “About the 1940 Census,” National Archives (https://1940census.archives.gov: accessed 28 January 2018).

(2) “Sixteenth Decennial Census of the United States. Instructions to Enumerators. Population and Agriculture. 1940,” US Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/1940instructions.pdf: accessed 27 January 2019). Page 4.

(3) Ibid. pg. 31-32.

(4) Ibid. pg. 42.

(5) Ibid. pg. 9.

(6) Ibid, pg. 43.

Related Article:

The 1940 census listed the middle initial first. I am Charles J, my father is Oscar J. We are shown as J Charles and J Oscar. Codes and “additions” were apparently added later –- lighter and different ink noted -– even on your examples. Apparently, the enumerator for me, as I was a baby, did not list sex, schooling, marital status, or state of birth. These were all added later with the light colored ink, and, in the case of State of Birth, was wrong!!! Whoever coded the census made incorrect assumptions!! They were probably not the enumerator?

Charles, that’s a good question. It’s possible the enumerator did that later or another census employee or even supervisor did that coding. As to the wrong information about you, who was the informant for your information? Was it a household member?

Thank you so much for your well-written, informative article; I appreciate it!

Thank you, Mary. I appreciate that!–Gena

Sometimes even those reporting didn’t get it right! I have a relative whose parents divorced prior to 1940. One lived in Maine and one in Massachusetts. The relative, who was almost 10 at the time of the census, remembers living with the Massachusetts parent. The Maine parent said that this relative was living in Maine with them. The relative is not recorded in Massachusetts! When I showed the census to the relative, they felt that the discrepancy was due to wanting a tax deduction!

Even when the person providing the information is the best informant, they can still not tell the truth, accidentally give wrong information, or just have forgotten. Your example is a great one to show that even the best informant might not provide the best information! Janet, thanks for sharing it!

Very interesting, I was unaware of the X in identification. Thanks.

Thanks for commenting Herb! It’s such a great addition to the 1940 census and provides researchers with important information.

My paternal grandparents divorced. On the next census they both reported themselves as widowed though both were still alive. On the maternal side, grandpa died. Grandma later remarried to a man 10 years younger than herself. She adjusted her age on the next census to make herself younger than her new husband. You have to look at all the other records to get the truth.

Absolutely! You have to follow-up with additional sources. Census information gives us some great clues but it can be incorrect for all kinds of reason. Thanks for sharing your experience Lynn Marie!