Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega gives tips for researching another aspect of your ancestor’s life: their home. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

Family historians research their ancestors’ lives – but there’s more to family history than names, dates, and places. Consider researching other aspects of your ancestors’ life to truly understand who they were. Researching what an ancestor owned or where they lived helps to add context to their overall story. It also may help you understand the records you have previously found.

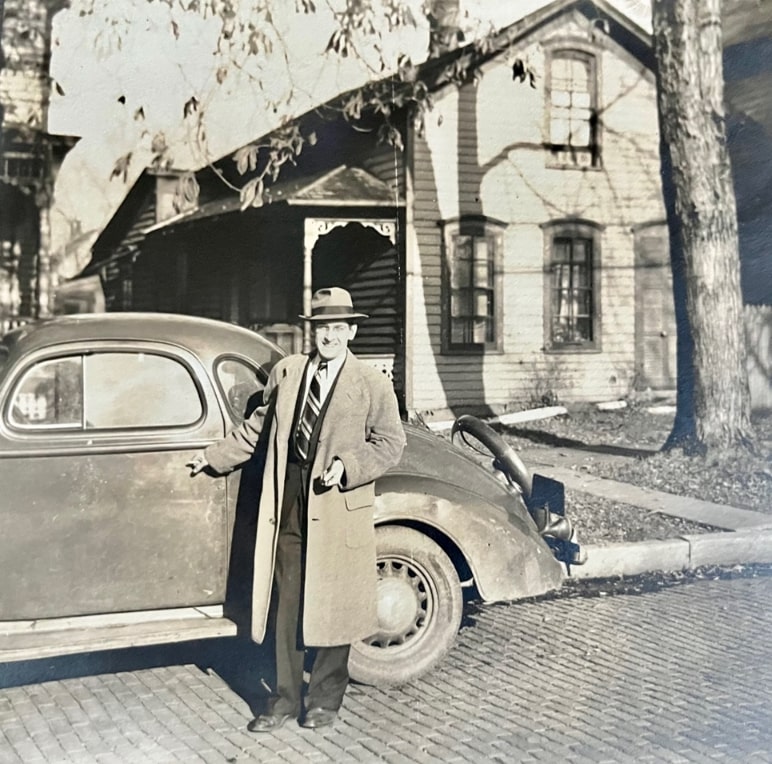

A house history is one type of research genealogists conduct on their ancestor’s life. By researching a home, genealogists can add depth to their genealogy. Conducting a house history entails researching the home by gathering records like deeds, mortgages, tax records, lawsuits, maps, and photographs. Historical newspapers can make important additions to a house history. Articles and mentions of tax debt, ownership, or even disasters can add to the other records you find that tell the story about that place.

How do you get started researching a house history? The three steps below will help you begin this research.

Genealogy Tip: There’s more than one way to search for an ancestor. Don’t just search by name. For example, conduct a search on your ancestor’s street address, if applicable.

First: Gather and Document What You Know

As with any research, always start with the known and work backward. What does this mean in relation to researching a house?

First, document what you know about the house. Don’t worry if you know very little. Every little bit helps.

Once you document what you know, continue by describing the house. This might be an ongoing project that will rely on some information found in your home or online, and has to be finished by visiting the home or libraries and archives. To do this documentation, think in terms of how a real estate agent might describe the house.

- The year the house was built

- What style the house is

- The size of the house

- Building materials

- How many stories

- How many and what types of rooms

- Does it have a basement or attic?

- Type of heating/cooling (if applicable)

- Land acreage that it sits on

- Additional buildings (garage, barn, casita, etc.)

- Interesting features

- Description of neighborhood

- Any damage the house has sustained such as from a natural disaster

- Any known history of the house (such as a kit home, or built for a specific reason)

If the house is still standing, you might be able to use an online real estate website (Zillow, for example) to find the actual home and a description of it by searching the address.

When you’ve documented as much as you know, start asking research questions. You now know what you know – now you need to explore what you don’t know. Write down questions about the house that you have. These may include the names of previous owners and when they owned the home.

Second: Research Online

Now, start searching online for information about the house. Researching a county government website, such as the Recorder’s office, might help with finding the names of previous owners or deeds. A historical map website might provide appropriate maps for when the house was built. A map for that time and place can help you follow any changes in ownership or boundaries over time. Look for land ownership maps, such as plat maps, and other types of maps to learn what you can about the home, its address, and neighborhood.

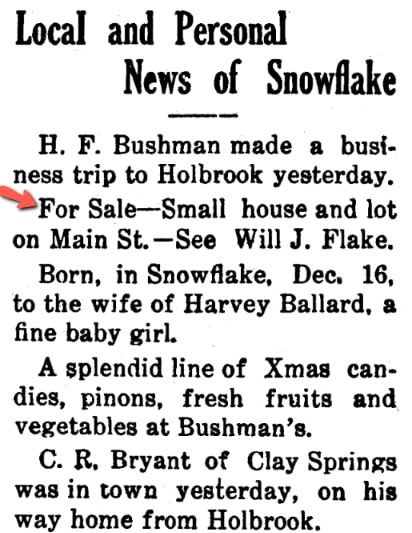

Search historical newspapers. If you know the names of owners, you can search for their names. Otherwise, search on the address to find articles that you may otherwise miss. Don’t forget to note if the address has changed over time. In a small town, a house may not have had a street address. Or maybe at a point it was known by a rural route number for mail delivery. Use any or all addresses, including just the street name, for that house.

Third: Take a Trip

Not everything is online. That’s true whether you’re researching your great-grandparents or their home. Researching a home may require trips to libraries, archives, courthouses, and county government offices. Where you need to research in-person will depend on your research questions and where the answer can be found. Researching in-person can be key and, in some cases, nothing substitutes for researching in the place your ancestor lived – but make sure to exhaust everything online first.

Identify local repositories such as applicable government offices, the courthouse, public and academic libraries, historical societies, and archives. If asking for help, make sure to provide what you know and what your research question is so that the helper can determine what records are needed.

Start a House History Project

Where did your ancestor live? Start thinking of your genealogy in a different way: research the history of their house. This research might open up records that you wouldn’t have normally searched, which in turn might tell you something new about your ancestor’s life.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial