Readers of the New York Herald picked up their papers on 14 April 1861 and learned that Fort Sumter had surrendered the previous afternoon after enduring a 34-hour bombardment – the opening battle of the Civil War had ended with a Confederate victory.

The war began when the first mortar was fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, on April 12. The Herald’s front-page story on April 13 began with the simple sentence: “Civil war has at last begun.” (See: Fort Sumter Attack Begins the Civil War.) Now, the next day, the Herald’s readers learned about the first Union defeat.

Here is the Herald’s Fort Sumter surrender story.

The Herald’s correspondent in Charleston churned out a series of rapid dispatches to keep the newspaper’s readers informed of the battle and the entire scene at the waterfront, capturing a wealth of details in his firsthand reporting.

Here is a transcript of this article:

The War.

The Conflict at Charleston.

The Bombardment Fiercely Continued.

Fort Sumter on Fire.

Major Anderson’s Men on Flotillas Dipping Water to Stop the Blaze.

The Men Fired Upon from the Forts.

The Surrender of Fort Sumter.

The Bombardment Ceased.

The Fort Evacuated.

Major Anderson the Guest of General Beauregard.

No One Killed in the Conflict.

All the Federal Officers Unhurt.

Blockade of the Port of Charleston.

Effect of the War News in the North and South.

Intense Excitement throughout the Free States.

Threatening Speech of Secretary Walker at Montgomery.

Sympathy of the Nova Scotia Legislature, &c.

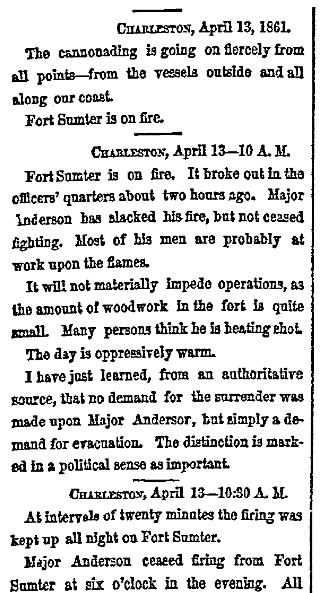

Charleston, April 13, 1861

The cannonading is going on fiercely from all points – from the vessels outside and all along our coast. Fort Sumter is on fire.

Charleston, April 13, 10 a.m.

Fort Sumter is on fire. It broke out in the officers’ quarters about two hours ago. Major Anderson has slacked his fire, but not ceased fighting. Most of his men are probably at work upon the flames. It will not materially impede operations, as the amount of woodwork in the fort is quite small. Many persons think he is heating shot.

The day is oppressively warm.

I have just learned, from an authoritative source, that no demand for the surrender was made upon Major Anderson, but simply a demand for evacuation. The distinction is marked in a political sense as important.

Charleston, April 13, 10:30 a.m.

At intervals of twenty minutes the firing was kept up all night on Fort Sumter.

Major Anderson ceased firing from Fort Sumter at six o’clock in the evening. All night he was engaged in repairing damages and protecting the barbette guns on the top of the fort. He commenced to return fire at seven o’clock this morning.

Fort Sumter seems to be greatly disabled. The battery on Cummings’ Point does Fort Sumter great damage. At nine o’clock this morning a dense smoke poured out from Fort Sumter. The federal flag is at half-mast, signaling distress.

The shells from Fort Moultrie and the batteries on Morris Island fall into Major Anderson’s stronghold thick and fast, and they can be seen in their course from the Charleston Battery. The breach made in Fort Sumter is on the side opposite Cummings’ Point. Two of its portholes are knocked into one, and the wall from the top is crumbling.

Three vessels, one of them a large-sized steamer, are over the bar, and seem to be preparing to participate in the conflict. The fire of Morris Island and Fort Moultrie is divided between Fort Sumter and the ships-of-war. The ships have not as yet opened fire.

Charleston, April 13, Later

An explosion has occurred at Fort Sumter, a dense volume of smoke ascending. Major Anderson ceased to fire for about an hour. His flag is still up. It is thought the officers’ quarters in Fort Sumter are on fire.

Charleston, April 13, 12 noon

The ships in the offing appear to be quietly at anchor. They have not fired a gun yet.

The entire roof of the barracks at Fort Sumter are in a vast sheet of flame. Shells from Cummings’ Point and Fort Moultrie are bursting in and over Fort Sumter in quick succession.

The federal flag still waves.

Major Anderson is only occupied in putting out fire. Every shot on Fort Sumter now seems to tell heavily.

The people are anxiously looking for Major Anderson to strike his flag.

Charleston, April 13, Later

Two of Major Anderson’s magazines have exploded. Only occasional shots are fired at him from Fort Moultrie. The Morris Island Battery is doing heavy work. It is thought that only the smaller magazines have exploded.

The greatest excitement prevails. The wharves, steeples and every available place are packed with people.

The United States ships are in the offing, but have not aided Major Anderson. It is too late now to come over the bar, as the tide is ebbing.

Charleston, April 13, Evening

Major Anderson has surrendered, after hard fighting, commencing at half past four o’clock yesterday morning, and continuing until five minutes to one today.

The American flag has given place to the palmetto of South Carolina.

You have received my previous despatches concerning the fire and the shooting away of the flagstaff. The latter event is due to Fort Moultrie, as well as the burning of the fort, which resulted from one of the hot shots fired in the morning.

During the conflagration, Gen. Beauregard sent a boat to Major Anderson, with offers of assistance, the bearers being Colonels W.P. Miles, and Roger Pryor, of Virginia, and Lee. But before it had reached him a flag of truce had been raised. Another boat then put off, containing ex-Governor Manning, Major D.R. Jones and Colonel Charles Allston, to arrange the terms of surrender, which were the same as those offered on the 11th inst. These were official. They stated that all proper facilities would be afforded for the removal of Major Anderson and his command, together with the company arms and property, and all private property, to any post in the United States he might elect. The terms were not, therefore, unconditional.

Major Anderson stated that he surrendered his sword to General Beauregard as the representative of the Confederate government. General Beauregard said he would not receive it from so brave a man. He says Major Anderson made a staunch fight, and elevated himself in the estimation of every true Carolinian.

During the fire, when Major Anderson’s flagstaff was shot away, a boat put off from Morris Island, carrying another American flag for him to fight under – a noteworthy instance of the honor and chivalry of the South Carolina seceders, and their admiration for a brave man.

The scene in the city after the raising of the flag of truce and the surrender is indescribable – the people were perfectly wild. Men on horseback rode through the streets proclaiming the news, amid the greatest enthusiasm.

On the arrival of the officers from the fort they were marched through the streets, followed by an immense crowd, hurrahing, shouting, and yelling with excitement.

Several fire companies were immediately sent down to Fort Sumter to put out the fire and any amount of assistance was offered. A regiment of eight hundred men has just arrived from the interior, and has been ordered to Morris Island, in view of an attack from the fleet, which may be attempted tonight.

Six vessels are reported off the bar, but the utmost indignation is expressed against them for not coming to the assistance of Major Anderson when he made signals of distress. The soldiers on Morris Island jumped on the guns every shot they received from Fort Sumter while thus disabled, and gave three cheers for Major Anderson and groans for the fleet.

Col. Lucas, of the Governor’s staff, has just returned from Fort Sumter, and says Major Anderson told him he had pleasanter recollections of Fort Moultrie than Fort Sumter. Only five men were wounded, one seriously.

The flames have destroyed everything. Both officers and soldiers were obliged to lie on their faces in the casements to prevent suffocation. The explosions heard in the city were from small piles of shell, which ignited from the heat. The effect of the shot upon the fort was tremendous. The walls were battered in hundreds of places, but no breach was made.

Major Anderson expresses himself much pleased that no lives had been sacrificed, and says that to Providence alone is to be attributed the bloodless victory. He compliments the firing of the Carolinians, and the large number of exploded shells lying around attests their effectiveness.

The number of soldiers in the fort was about seventy, besides twenty-five workmen, who assisted at the guns. His stock of provisions was almost exhausted, however. He would have been starved out in two more days.

The entrance to the fort is mined, and the officers were told to be careful, even after the surrender, on account of the heat, lest it should explode.

A boat from the squadron with a flag of truce has arrived at Morris Island, bearing a request to be allowed to come and take Major Anderson and his forces. An answer will be given tomorrow at nine o’clock.

The public feeling against the fleet is very strong, it being regarded as cowardly to make not even an attempt to aid a fellow officer.

Had the surrender not taken place, Fort Sumter would have been stormed tonight. The men are crazy for a fight.

The bells have been chiming all day, guns firing, ladies waving handkerchiefs, people cheering, and citizens making themselves generally demonstrative. It is regarded as the greatest day in the history of South Carolina.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in the Civil War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Civil War Genealogy Articles:

My G-grandfather served as a Union soldier in the Civil War, and was badly wounded in battle as a result. When left on the battlefield, believed to have been killed, it was discovered by General Grant himself after the battle that he was still alive. My G-grandfather survived to return to civilian life. Living in Kansas he met, courted and married my G-grandmother and together they had four children, the youngest of which was named Grant , in honor of General Grant who discovered him and saved his life. My G-grandfather died from lung related illness attributed to injury received in the war, when his son Grant was an infant, leaving my now-twice widowed G-grandmother to raise her family of four children on their Kansas farm. She later traveled to Montana via covered wagon to homestead a property on the Yellowstone river, taking young son, Grant, with her on the journey. The three older children were left in the care of relatives until they could be reunited in Montana at a later date.

Thanks for writing us, Sharon, and sharing this incredible story about your ancestors!