Introduction: In this article – to help celebrate Independence Day on July 4 – Melissa Davenport Berry writes about Minutemen at the Battled of Lexington and Concord, and provides genealogy. Melissa is a genealogist who has a website, americana-archives.com, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

“They poured out their generous blood like water before they knew whether it would fertilize the land of freedom or of bondage.”

–Daniel Webster

Today I continue with my series “Spirit of ’76” in honor of Independence Day, aka “Fourth of July,” focusing on the Minutemen and militiamen of Massachusetts who fought at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, on 19 April 1775.

My last story covered Revolutionary trail blazer Isaiah Thomas, who published the Massachusetts Spy newspaper. Thomas performed the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence in Worcester, Massachusetts. Read more: Part 2.

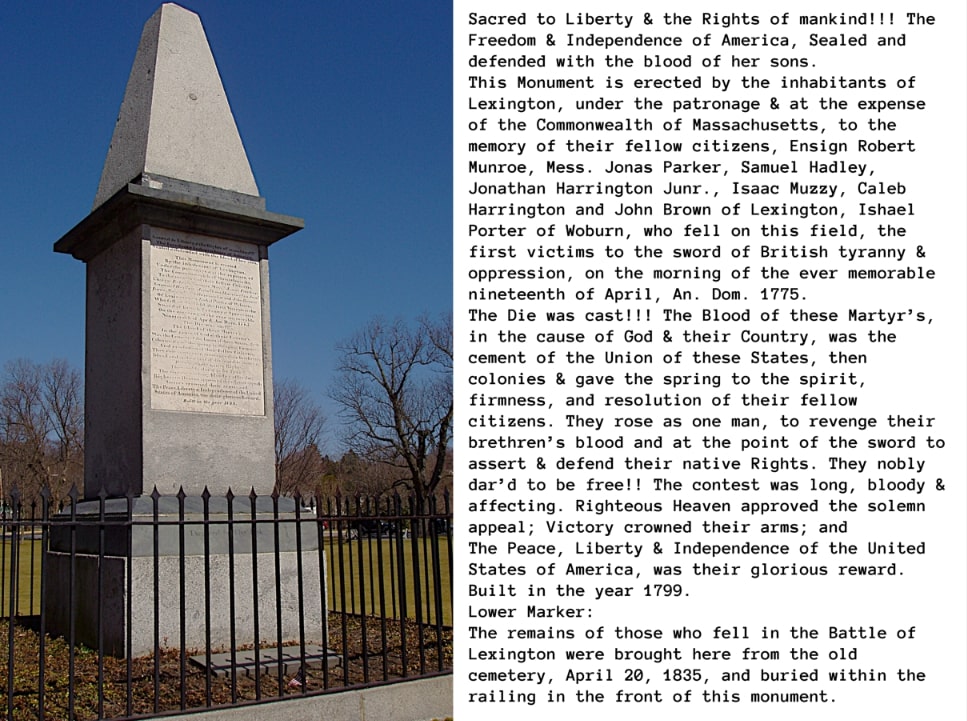

Lexington Battle Monument

The names of the eight militiamen who were killed in the first battle of the Revolutionary War can be found on the Revolutionary Monument on Lexington Battle Green, erected in 1799 by the town’s citizens.

Munroe Clan & Family Tavern

Ensign Robert Munroe (1712-1775), son of George and Sarah (Mooer) Munroe, was one of the eight militiamen killed by the British during the Battle of Lexington. He left his widow Anna (Stone) Munroe and descendants.

Robert’s sister Lucy (Munroe) Parker lost her husband Jonas Parker (1722-1775) during the battle, the son of Andrew and Sarah (Whitney) Parker. Jonas and Lucy had one son, Pvt. Philemon Parker, who married Susannah Stone and left many descendants.

The Munroes’ cousins owned a tavern in Lexington. According to the annuals, on 18 April 1775, one day before the outbreak of the battle, the Munroe Tavern (now the Lexington Historical Society) was a meeting spot for colonials.

By the following afternoon Colonel Hugh Percy and his 1,000 British reinforcements occupied the tavern and converted the dining area into a field hospital for the wounded.

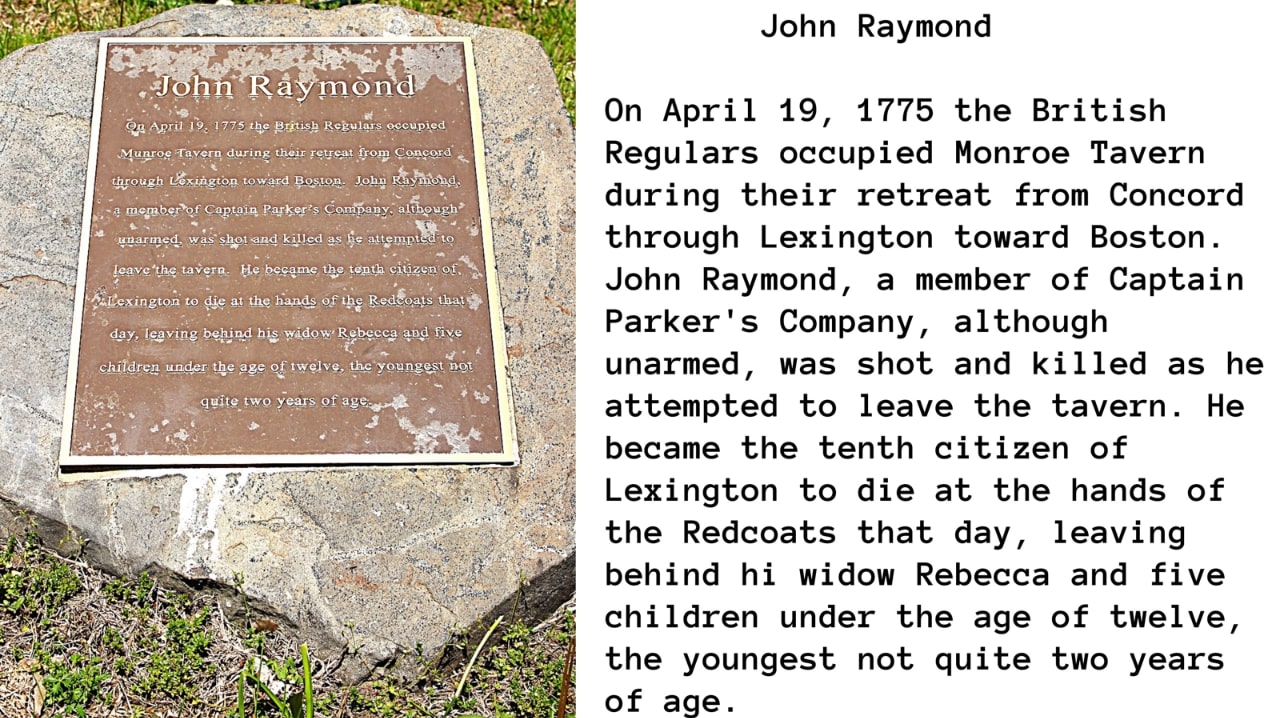

The British troops consumed liberal quantities of food and drink, compelling a Lexington Minuteman, John Raymond – who was lame – to serve as their bartender. Raymond tried to escape, but he was shot and killed on the spot.

In November of 1789 President George Washington dined at the Munroe Tavern during his tour throughout the states. His hosts were William and Anna Parker (Smith) Munroe.

Washington wrote in his journal: “viewed the spot on which the first blood was [spilled] in the dispute with Great Britain.” An upstairs room in the tavern now contains the table and chair at which he sat, and documents relating to his trip.

The Bedford Flag Carried by the Militiamen

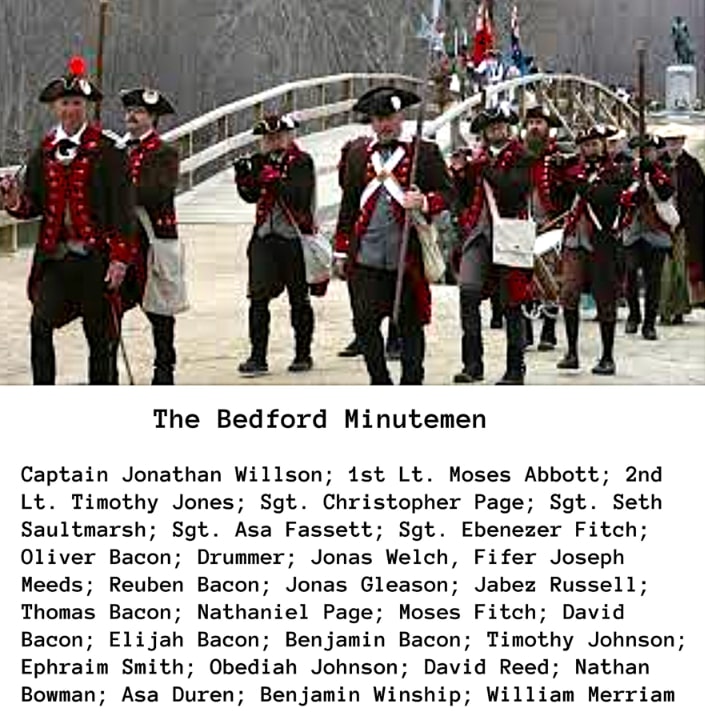

According to Bedford, Massachusetts, history sources, early in the day on 19 April 1775 the Minutemen of Bedford gathered in the tap room of Jeremiah Fitch’s tavern while his wife Lydia (Smith) Fitch served up cold cornmeal mush and hot buttered rum.

Captain Jonathan Wilson looked into the eyes of his men and spoke the famous words: “It is a cold breakfast, boys, but we’ll give the British a hot dinner; we’ll have every dog of them before night.” The Minutemen then marched to Concord, joining the 50 men of the Bedford Militia en route.

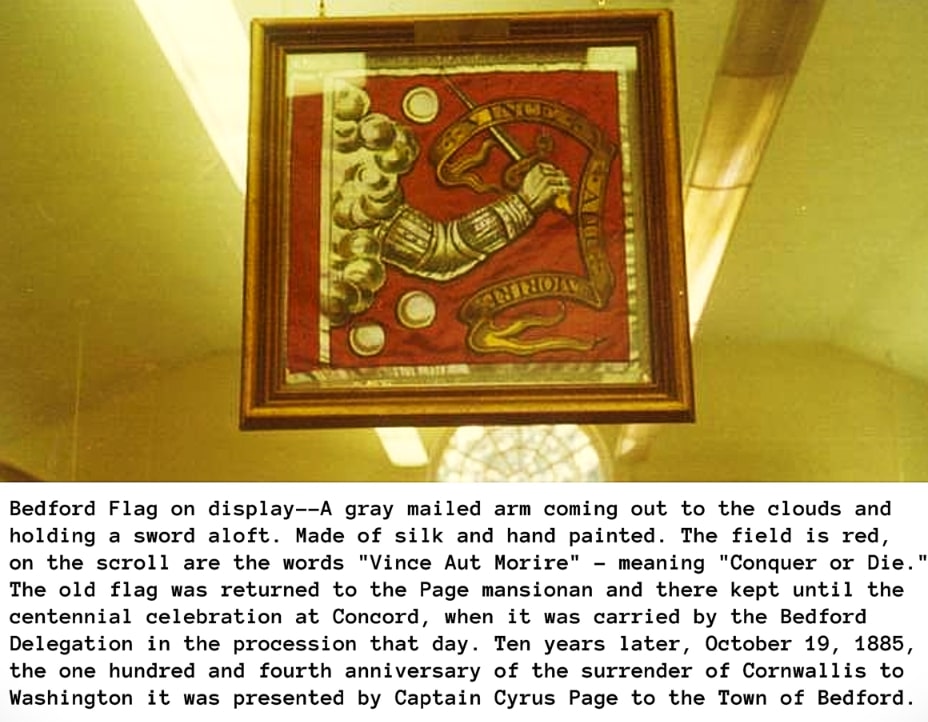

Included in the Bedford Militia was Color Bearer and Captain Nathaniel Page/Paige, who carried the famous Bedford Flag now in the safekeeping of the Bedford Historical Society.

The flag was given to the society by Captain Cyrus Page, grandson of Nathaniel. I found a newspaper article entitled “Flag of the Minute Men,” which cites some well-known historians on the flag.

This article reports:

William S. Appleton of the Massachusetts Historical Society writes of this flag: “It was originally designed in England in 1660-70 for the three county troops of Middlesex, and became one of the three accepted standards of the organized militia of the state, and as such was used by the Bedford [Militia] company. In my opinion this flag far exceeds in historic value the famed flag of Eutaw and Pulaski’s banner, and in fact is the most precious memorial of its kind of which we have any knowledge.”

Historian Abram English Brown, in “Flag of the Minute Men, April 19, 1775, Its Origin and History,” provides a detailed history of the day of the battle, when:

“Delegates from Captain Jonathan Parker’s company, of Lexington, gave the alarm at Bedford. The messengers found a ready response… the old standard [flag] was in the Page family, and the office of cornet, or color-bearer, was a sort of inheritance, hence Nathaniel Page, aroused by the early messenger, seized the relic of early service and hastened with his associates to the scene of action.”

Captain Jonathan Wilson (1733-1775) was killed that day. He left a widow Elizabeth (Stearns) Wilson and one son, Jonathan Wilson Jr., who married Rebekah Page, and left descendants.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: “The Spirit of ’76,” by Archibald Willard. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Related Articles: