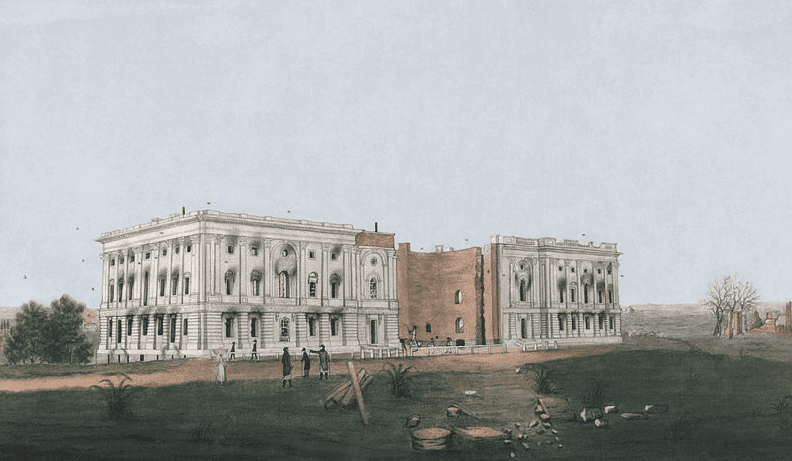

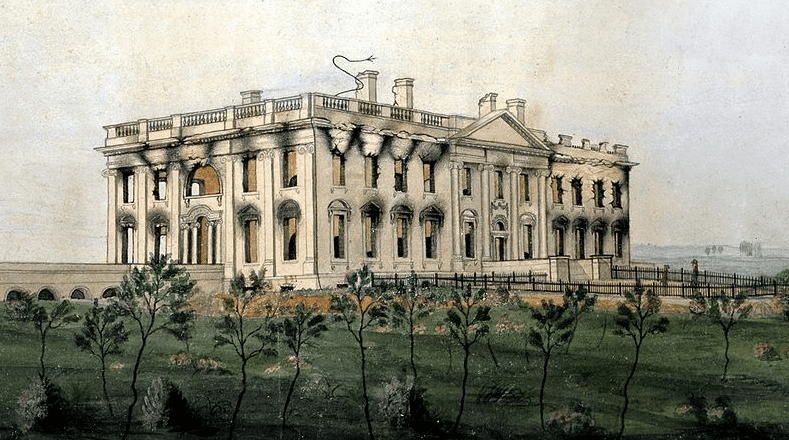

On 24 August 1814, one of the most humiliating events in American history occurred when British troops occupied Washington, D.C., during the War of 1812. They flew the Union Jack on top of Capitol Hill and burned the public buildings in the young nation’s capital – including the Capitol Building (missing its uncompleted rotunda), President’s House (i.e., White House), and Treasury Building.

The British occupation was purely a retaliatory action – Washington, D.C., held no military significance. There were no American casualties, the British did not seize any territory, and shortly after their arson work was done the British abandoned their enemy’s capital. Their objective was revenge, and it had been accomplished.

What provoked the ire of the British was the action of the victorious American troops after the Battle of York in May, even though the War of 1812 was still governed by “rules of civilized warfare” that forbade attacks on non-military targets. However, the Americans had looted York (i.e., Toronto) and burned Parliament, the Governor’s house, and some private homes. Incensed, the British vowed revenge, and on 24 August 1814 they got it.

Although it had been the nation’s capital since 1800, Washington, D.C., was woefully unprepared to defend itself. The administration of President James Madison was convinced the British intended to attack Baltimore, a much more valuable target, and would have no interest in attacking the capital.

However, when a force of nearly 7,000 American troops, mainly militia, was routed by 4,500 British regulars at the Battle of Bladensburg on 24 August 1814 – only a few miles from Washington, D.C. – the British intent became known. The routed American militia fled through the capital’s streets in a panicked retreat, along with the president, government officials, and most of the city’s civilians. The British marched into America’s capital unopposed.

One of the most grievous losses caused by the British fires was the complete destruction of the original Library of Congress, over 3,000 rare volumes. The gorgeous interiors of the Capitol Building and the White House were destroyed as well. To this day, soot marks on the outside of the White House’s walls bear testimony to the British success of that 1814 raid.

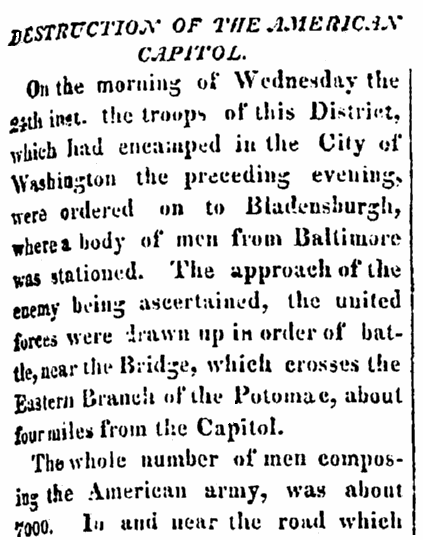

Here is a transcription of this article:

Destruction of the American Capitol

On the morning of Wednesday the 24th inst. the troops of this District, which had encamped in the City of Washington the preceding evening, were ordered on to Bladensburg, where a body of men from Baltimore was stationed. The approach of the enemy being ascertained, the united forces were drawn up in order of battle, near the bridge, which crosses the Eastern Branch of the Potomac, about four miles from the Capital.

The whole number of men composing the American army was about 7000. In and near the road which leads to the city, Com. Barney’s men and the marine corps were posted, with a formidable battery of artillery. In their rear to the left of the road, was Major Peter’s artillery. Another battery of six pieces from Baltimore was placed in such a position on the left as to rake the bridge, and was covered by a rifle corps. The infantry of the District under the command of Gen. Smith, were placed on the left of the road. Gen. Stansbury’s brigade, of which the noted Mumma is a member, and the 5th Baltimore Regiment under Col. Sterett, were posted further to the left, the extreme of which was brought up by Capt. Burch’s artillery and Capt. Doughty’s riflemen.

About half past 12 o’clock the enemy’s advance appeared and pushed for the bridge, when the Baltimore artillery opened a galling fire upon them. They proceeded on with great rapidity, and passing the bridge divided into two columns. One charged on the Baltimore artillery and compelled them to retreat. Burch’s artillery, 5th Baltimore Regiment and Stansbury’s brigade began firing, but an apple orchard prevented the fire of the latter being effective. The other column proceeded along the road, the passage of which was gallantly contested by Barney and the marines under Captain Miller.

The battle continued about three quarters of an hour. The 5th Baltimore Regiment maintained their ground with firmness and fought well. Stansbury’s brigade gave way as soon as exposed to the enemy’s fire, and the general himself, as we have been assured by several officers, was the first in flight. The example of these men was soon followed by the militia of the District, and a general retreat was ordered before all the troops were brought into the action.

Great praise is due to Barney’s men, who fought with desperation as did the marine corps. Com. Barney and Capt. Miller of the marines, were both severely wounded and were taken prisoners, with many of their men also wounded. All the volunteer corps of the District displayed great bravery, and no want of firmness was shown by the militia until after the flight of Stansbury’s men.

The right wing which had no share in the action, was composed of the regular troops, belonging to the 36th and 38th Regiments, amounting to 500, and part of the militia from Montgomery, Alleghany and Prince George Counties, in Maryland, and several hundred men from Virginia.

The retreat was rapid and disorderly. At Capitol Hill the district volunteers and some companies of militia were rallied, but orders were given to continue the retreat, and the inhabitants of Washington and Georgetown had the mortification to see the whole body pass through their streets in disgraceful flight.

The retreat was continued till the troops reached Montgomery courthouse, 13 miles from the battleground, almost exhausted with fatigue, and without camp equipage, the baggage wagons having been sent across the Potomac bridge and ordered up the Virginia shore.

Before the retreating troops reached Georgetown, the secretary of the navy passed through the place, and recommended to the citizens to make the best terms they could with the enemy. The President made his escape by crossing Mason’s ferry into Virginia. The second day after the battle he passed through Rockville, Montgomery County, to Brookville, in the same county, where he arrived at nine in the night, escorted by twenty dragoons. He was taken in at the house of one of the Society of Friends, having “rode thirty miles since breakfast,” as he stated, “over a dreadful road, without any dinner.” The next day being joined by Col. Monroe, he found his way to the District, late in the evening, and his quarters have since been at the houses of his different friends.

No pursuit was kept up by the enemy, who entered Washington at his leisure, and in the evening, with one hundred men, destroyed the Capitol, the President’s House [i.e., the White House], and the Treasury Office. A few of our men left at the Navy yard destroyed, by order, the sloop of war Argus, the frigate on the stocks, and the public buildings there, and the arsenal at Greenleaf’s Point.

The General Post Office was spared on the representation of Dr. Thornton, that a part of the building was a museum of the arts, containing models of the patent machines, and the cause of general science would suffer by its conflagration.

On Thursday the War Office and two rope-walks in Washington were burnt. In the evening a party was dispatched to Greenleaf’s Point, and while employed in burning a number of gun-carriages, a quantity of powder which had been thrown into a well, exploded and destroyed a considerable number of men and mangled many others.

After the retreat of the troops called to the defense of the Capital, the enemy took possession of the battleground and many of them actually sank to the ground with fatigue. They rested on their knapsacks, and were so exhausted by their rapid march, carrying on their backs four days’ provision and eighty rounds of cartridges, that they were unable to follow up the advantage gained, and pursue our army on their route through the city. The force that marched to the city two hours after the skirmish at Bladensburg, consisted of about 1500 men, that were not in the action, as it terminated before they could be brought up. They proceeded slowly and with the greatest caution, as they apprehended an ambuscade, and were persuaded the decisive battle was yet to be fought, which was to decide the fate of the late city of Washington. Arrived at the entrance of the town, opposite Mr. Gallatin’s late dwelling, [British] Gen. Ross, at the head of his troops, halted, expecting that the city would propose terms of capitulation. While in this situation, a shot from Gallatin’s house killed the horse on which Gen. Ross rode. The house was instantly set on fire and orders were at once given to burn the Capitol.

We have stated nothing that we do not religiously confide in as true. We have many precious anecdotes which will be given at leisure. In the present situation of affairs, when all is confusion and alarm, and we can scarcely be said to have a government, we have been barely able to get our paper to press, but when order and security are restored our readers will receive all the information it may be in our power to give them.

At a late hour on Thursday night, the British troops evacuated the city, leaving behind them the men wounded by the explosion.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in the War of 1812? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles: