Introduction: In this second article, Katie Rebecca Merkley writes more about her lifelong love of the author Louisa May Alcott, especially her novel “Little Women.” Katie specializes in U.S. research for family history, enjoys writing and researching, and is developing curricula for teaching children genealogy.

In this century, celebrities’ doings are often posted on social media. Some people follow their favorite celebrities, checking every notification to see what the star is up to. Celebrities would have been authors, war heroes, and influential politicians in our ancestors’ times. These people were talked about in newspapers.

If your ancestors wanted to follow a favored celebrity, they would have scanned the newspapers for mentions of them. One such famous person was author Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888), who wrote Little Women.

Life Story

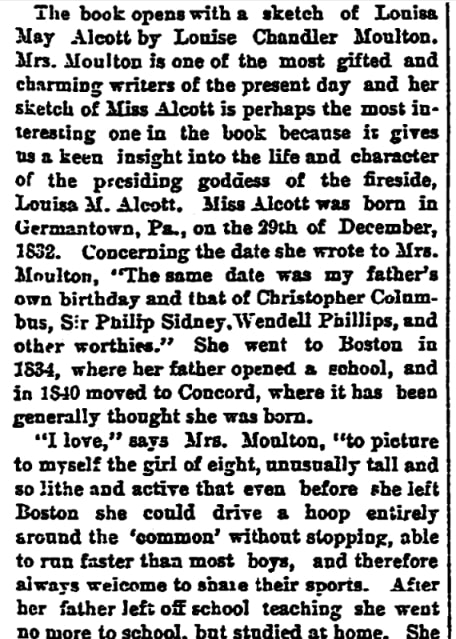

A group of biographers wrote a book about famous women – the first sketch being about Louisa May Alcott. A Cleveland newspaper from 1884 talks about this book and summarizes the sketches of a few of the women featured. Miss Alcott’s sketch was written by Louise Chandler Moulton. The newspaper article says the sketch about Miss Alcott is the most interesting in the book.

This article has gems such as this description of Louisa May as a little girl:

“…the girl of eight, unusually tall and so lithe and active that even before she left Boston she could drive a hoop entirely around the ‘common’ without stopping, able to run faster than most boys, and therefore always welcome to share their sports. After her father left off school teaching she went no more to school, but studied at home. She learned religion from nature and the high example of virtuous parents, who literally loved their neighbors better than themselves, and in the pure atmosphere of whose daily life it was impossible that anything small or mean should thrive.”

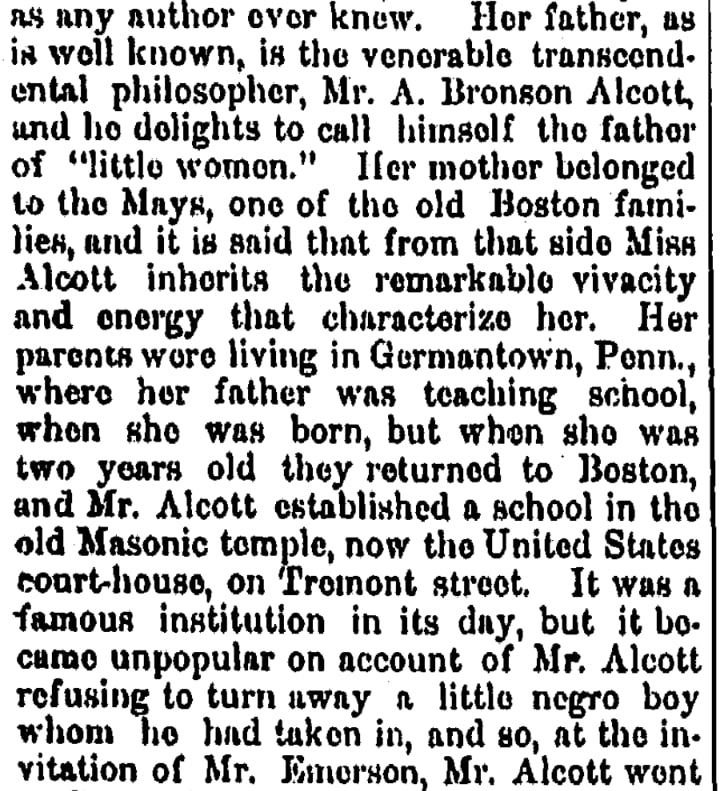

Other journalists in the late 1870s and early 1880s wrote about her for their newspapers. All the biographers agreed she was born in Germantown, Pennsylvania. One account indicates her parents were in Germantown because her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, was teaching school there at the time.

All accounts agree that the Alcotts moved to Boston when Louisa was two, and that Mr. Alcott established a school there. People complained that Mr. Alcott was too gentle with the students and read the Bible to them too much. The school declined in popularity when he refused to turn away a poor colored boy. The white parents took their children out of the school “not willing to have a colored child in the same school with their darlings.” Eventually, Mr. Alcott was down to five pupils, including his three daughters and the African American boy. At this point, Mr. Alcott had become poor and had to give up the school. (1)

When Louisa was eight, a family friend – author and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson – invited Mr. Alcott to move to Concord, Massachusetts, so he took his family there in 1840.

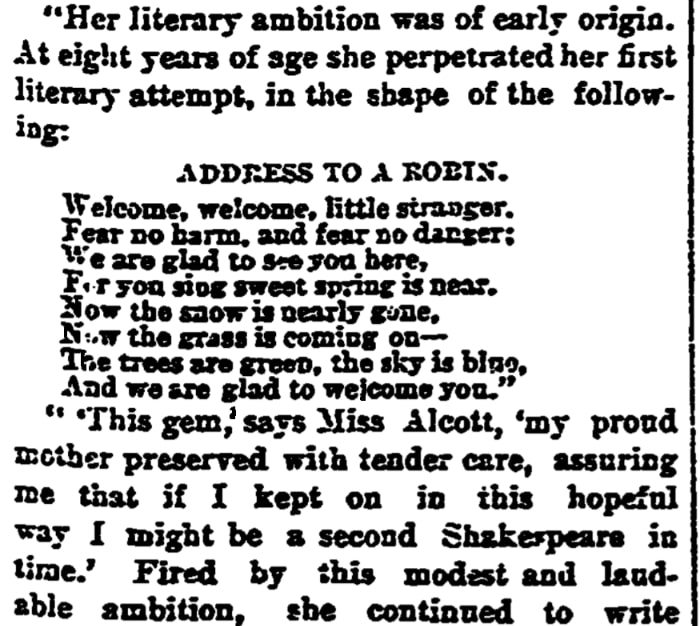

Louisa May Alcott began writing at a young age. A poem she wrote at age eight was included in one of these biographies. Her “proud mother preserved [that poem] with tender care.”

In 1843 the family moved to Harvard, where for two years the Alcotts lived with other families in a utopian farming community called “Fruitlands.” Louisa was ten when her father took them there and twelve when they returned to Concord. Upon returning to Concord, Mr. Alcott planted a garden and built a summer house for his children near a brook. There, “Miss Alcott first began to compose stories to amuse her sisters and other children of the neighborhood.” (2)

The Alcotts returned to Boston when Louisa was nearly 16, and Louisa May began teaching. She didn’t like teaching as much as her father did, so she wrote stories in hopes of getting paid for them. (3) She found writing the stories easy, but getting paid for them was difficult.

Louisa May wrote Flower Fables when she was 16, and it was published when she was 22. She was 19 when her first story was published in 1851. The story was dramatized but never performed. However, it gave Louisa a pass to the theater for that season. (4)

Miss Alcott hoped to earn her fortune in Boston. “She taught, sewed, wrote, and did what she could find to do.” (5)

Louisa May Alcott volunteered for the soldiers’ hospital in late 1862 during the Civil War and wrote about her experiences in Hospital Sketches. According to one account, she had been assigned to a hospital in Georgetown near Washington, D.C., one of the most unpleasant hospitals. (6) Another account states she helped poor soldiers until she became sick. She nearly died of typhoid fever and never fully recovered her health. “But was more or less an invalid while writing all those cheerful and entertaining books.” (7)

The four parts of Hospital Sketches were first published individually in Boston newspapers, such as the Commonwealth. Later compiled into a book, Hospital Sketches became popular and made her name known.

In 1868, Louisa May Alcott brought a collection of short stories to the publisher. The publisher turned them down, saying short stories didn’t sell well, and asked Louisa May Alcott to write a book for girls instead. Miss Alcott, a tomboy, wanted to write about boys because she “knew nothing of girls.” The publisher was insistent on a book about girls. Miss Alcot decided to write about herself and her sisters. This was how Little Women came to be.

The first volume of Little Women was so popular that the printers had trouble keeping up with the demand, and a second volume was demanded. Louisa May Alcott wrote a second volume and continued writing other books.

Death Announcements

As social media today will explode with posts about a celebrity when they die, so it was for our ancestors’ “social media” – newspapers. When Louisa May died, multiple newspapers posted announcements of her death. Many of these also included detailed life sketches.

Louisa May Alcott died 6 March 1888 in Boston. She died just two days after her father. She had been living with him, her widowed sister Mrs. Pratt (“Meg”), and her children.

The following newspaper article says that Miss Alcott had been ill a long time, “suffering from nervous prostration.” She appeared to be improving the prior autumn and went into the highlands. She drove into town to see her father and caught a cold Thursday the first, “which on Saturday settled on the base of the brain and developed spinal meningitis.” She died that morning (Wednesday).

Other obituaries were published for Louisa May in New York, Boston, and other places across the country. There are so many that there isn’t time to review them all.

Even long after her death, Louisa May Alcott’s legacy lives on. Her books are still popular, and seven movies and numerous TV series have been based on the beloved story of Little Women.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

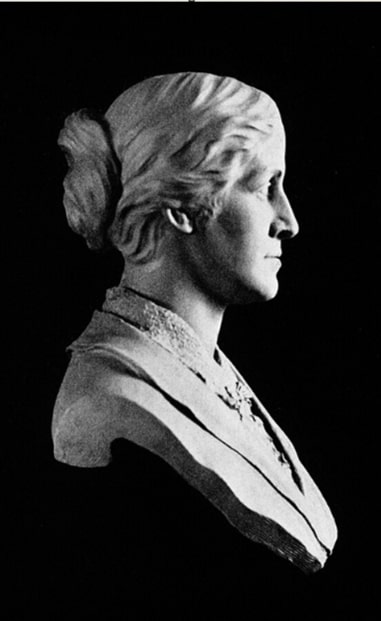

Note on the header image: Louisa May Alcott, from “Louisa May Alcott, Her Life, Letters, and Journals,” published by Little, Brown & Co, Boston, 1889. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Related Article:

______________

(1) “Miss Alcott,” The Vancouver independent (Vancouver, WA), 3 January 1878, p. 7

(2) “Miss Louisa M. Alcott,” Jackson Weekly Citizen (Jackson, MI), 4 May 1880, p.8

(3) Ibid.

(4) “Famous Women,” The Cleveland Leader (Cleveland, OH), 26 January 1884, p. 7

(5) Ibid.

(6) “Miss Louisa M. Alcott,” Jackson Weekly Citizen (Jackson, MI), 4 May 1880, p. 8

(7) “Miss Alcott,” The Vancouver independent (Vancouver, WA), 3 January 1878, p. 7