It has been more than a century now, and the notoriety of Lizzie Borden has begun to fade – but in 1893, the trial of Borden for the gruesome murder of her father and stepmother transfixed the press and public. It received scrutiny and publicity much the way the murder trial of O.J. Simpson did in 1995.

Even though Borden was acquitted, some were convinced that she did commit the murders, and children skipped rope to a popular sing-song rhyme:

Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her mother forty whacks.

When she saw what she had done

She gave her father forty-one.

The murder of Andrew Borden (Lizzie’s father) and Abby Borden (Lizzie’s stepmother) occurred on 4 August 1892, in the family home the two shared with Lizzie and her sister Emma. Andrew was killed by 11 blows with an axe or hatchet, and Abby by 18 – contrary to the nursery rhyme. Emma was away at the time, but Lizzie was home – and circumstantial evidence pointed to her as the killer.

There was tension in the family, as Andrew had begun dividing up his property and giving some to Abby’s family, causing arguments and discontent. Lizzie disliked her stepmother, and the four family members rarely shared meals together. Lizzie kept pigeons in the barn behind the house, but her father had chopped their heads off with an axe to discourage neighborhood boys from snooping around. The day before the murders, Lizzie had tried to buy some poison (hydrogen cyanide) at a local drug store.

A witness reported that on the morning of the murders, Lizzie had been wearing a blue dress. A few days after the murders Lizzie was seen tearing up a blue dress and burning it. At an inquest into the murders on August 9, Lizzie gave contradictory testimony, increasing suspicion of her guilt. She was arrested and jailed on August 11, and her murder trial began on 5 June 1893.

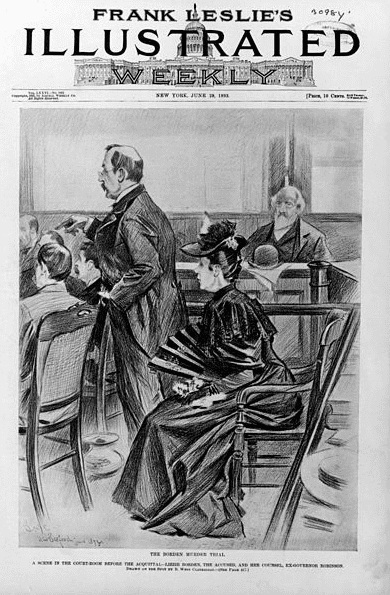

She was ably defended by Andrew V. Jennings and George D. Robinson, the former governor of Massachusetts. The jury seemed incredulous that a 32-year-old, single woman of known moral character and good standing in the community could commit such a bloody, horrific crime. The prosecution could not produce a murder weapon (a hatchet had been found in the basement, but it lacked a handle and had no blood on it), bloody clothing, or any physical evidence whatsoever linking Lizzie to the crime. All the evidence was circumstantial – not enough to prove her guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

On 20 June 1893, Lizzie Borden was acquitted after the jury deliberated only 65 minutes. No one else was ever arrested for the murders, and the crime went unsolved. Borden died 34 years later, at the age of 66; the notoriety of the murders and her trial outlived her.

The following two newspaper articles were published by the Boston Journal. Although the first article is ostensibly a news report of her acquittal and the second article an editorial praising the jury, the paper had been on Borden’s side throughout the trial – and the news article is as strongly opinionated as the editorial.

Here is a transcription of this article:

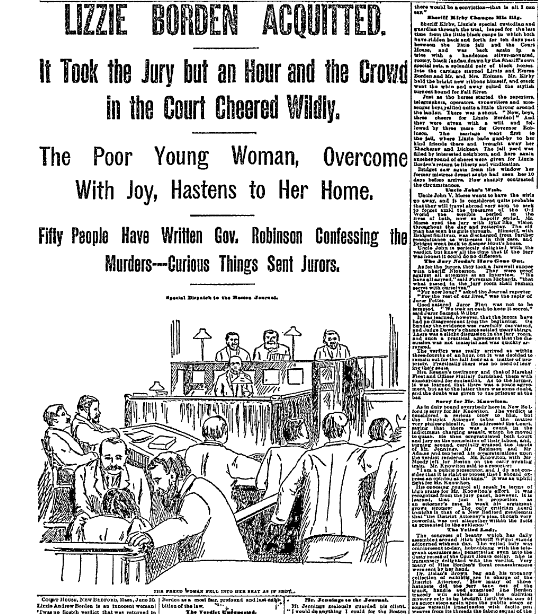

Lizzie Borden Acquitted

It Took the Jury but an Hour and the Crowd in the Court Cheered Wildly

The Poor Young Woman, Overcome with Joy, Hastens to Her Home

Fifty People Have Written Gov. Robinson Confessing the Murders

Courthouse, New Bedford, Mass., June 20. – Lizzie Andrew Borden is an innocent woman! ’Twas no Scotch verdict that was returned in today’s crowded courtroom. The finding of the twelve good men and true was broader than that. Such a verdict goes beyond the mere meaning which its phrase implies; it establishes the innocence of this woman; it lifts her from the sphere of suspicion and sends her forth again, with her head uplifted, to stand as a free-born American woman, void of guilt, among her sisterhood.

She has sore need of all their tender care and loving confidence, for she has been tried as they are not, and terribly has she been wronged – arrested by police who within twenty minutes after their arrival on the scene of the horrible tragedy fixed upon her at the beginning as the perpetrator of the double crime and remained stubbornly incredulous to any rational suggestion of subsequent probable clues which admitted the possibility of there being any mistake on their part; forced before a secret tribunal to endure for three days a merciless inquisition; then obliged to [sit] for hours at a prolonged, blood-curdling examination into the ghastly wounds of her murdered father; declared a Sphinx because, proving her innocence, she exhibited the courage to face her accuser; and finally, committed to prison for more than eight weary months of captivity, to be finally brought before the court of last resort, and there to go again through all this horror before a jury of her countrymen, and to sit by while a professional examiner fingered the mutilated skull of her father!

Truly might not this woman say she had finally suffered the torture of the damned? And yet through all and above it all, that poor woman’s trust and faith has triumphed. The rift has been found in that black and somber pall that has enveloped her, and through it all shines the light of proud innocence. In this case, if in no other, have they not “true deliverance made.”

Invited to Address the Jury

How striking the spectacle – not again witnessed probably in this day or generation – when a refined and cultivated woman, the daughter of a respectable and honorable citizen, her own father, with whose murder she is charged, is privileged by her Judges to address the jury in her own behalf before the final charge is made to those jurors who stood between herself and death, and how modestly Lizzie Borden did it! She rose very quietly and with perfect womanliness faced her jurors with gaze concentrated.

“I am innocent” was all she said; the rest her counsel had spoken for her. She came to them with perfect confidence, upheld by the belief that has sustained her throughout her long imprisonment, that when she did meet a jury of her people she would have justice.

It was enough. Did you notice how those jurors faced her, and how they looked upon her; was it not as though they stood like soldiers between her and her dread accusers, ready to do valiant battle in her cause? said one of her devoted counsel.

After [Borden’s statement] came the dignified charge of Judge Dewey to the jury, which, although to those actuated by belief rather than by the facts offered to supplement the arguments for the defense, seemed to those who have simply asked for a fair trial for Lizzie Borden as a most fair, profound and just exhibition of the law.

The Verdict Unexpected

How dear at heart the American people hold their love of fair play was never more strikingly attested than when, at half-past four, the jury returned to their seats, after an absence of 65 minutes. No one then expected a verdict, with nerves and emotions still pulsating from the terrible arraignment of the accused in the stirring appeal of the District Attorney.

It was quite probably only a request for instruction. Why the jury had been out not much over an hour yet; but Foreman Richards’s hands contained a paper, and a wave of nervous whispering ran over the crowded benches.

It was the most intense moment of this great trial. The rebellious nerves would not remain still, and, in spite of all attempts at calmness, the blood would thrill in one’s veins. So impressive was the silence that one might hear only the subdued breathing of those in the crowded bar and benches.

Lizzie Borden’s courage stood by her; the excitement buoyed her up.

“Hold up your right hand,” was the Clerk’s demand, and uplifted rose the delicately rounded arm and black-gloved fingers.

“Prisoner, look upon the jurors – jurors, look upon the prisoner!”

How tremendous the suspense. What is coming – and then:

You have agreed upon a verdict – The prisoner at the bar, Lizzie Andrew Borden, is not guilty so you say, Mr. Foreman, so you all say.

The Woman Asserts Herself

But long before that assent was reached the little woman in the dock had dropped down upon the rail, sinking almost as one shot, with her handkerchief over her eyes and her form shaking with feebly controlled emotion. Down went the head upon the rail, and Lizzie Andrew Borden’s overwrighted nature gave way at last in grateful tears.

Emma Borden was first to reach her sister’s side. She hastened across the bar, the sympathetic attorneys quickly making passage for her. Her head was under Lizzie’s cheek, and, comforted by her younger sister, she gradually grew calmer. Was there a dry eye in those rows of fair lady faces? Hardly, and even manly eyelids glistened.

Lizzie did not faint.

Chief Justice Mason had requested that there might not be any demonstration within the bar, and the word had been privately passed around; but the people were outside the rail. There was a single clap, and then such an outburst of applause as the old Bristol County Courtroom has not seen in years before, if ever in its history. The clapping was quickly drowned in one spontaneous hearty cheer from the relief valves of some of those who must have cried too but for this happy event.

Neither Bench nor Sheriff sought to restrain it or had the desire to until it had spent its force. The great heart of the people was touched in real sympathy.

But Lizzie remained with bowed head still, and it was many minutes before she finally raised it.

Downstairs raced the messenger boys and reporters. In two minutes the glad news had flashed over the wire directly into the Journal editorial rooms – the first dispatch to reach Boston. In five minutes it was known well nigh across the breadth of this wide land that the greatest trial this country has ever known had ended in the triumphant acquittal of Lizzie Andrew Borden upon the terrible charge brought against her.

Slowly the great assemblage separated. Chief Justice Mason announced to the jurors that they were now free to go to their homes and expressed the thanks of the Court to them. The twelve good men and true rapidly filed downstairs. Lizzie, Emma, Mr. and Mrs. Chas. J. Holmes, Governor Robinson and Mr. Jennings all repaired to the grateful retreat of the Judges’ room.

Mr. Jennings to the Journal

Mr. Jennings zealously guarded his client. “I would do anything I could for the Boston Journal,” he said, “for you have stood with us when everything was at its darkest, and we are all most grateful for the course your paper has taken. But I am going to do all that lies in my power and prevent any living reporter from seeing Miss Borden at present. You do not – nobody can – realize the tremendous strain she has had to bear for the past eight or nine months. She must have perfect rest and absolute quiet.

“What do I think of the verdict? I think it just the decision that every honest man must have arrived at who judged fairly of the evidence presented here. He could not help returning such a verdict.”

Gov. Robinson’s Voice

“I have told Lizzie,” said Gov. Robinson, “that she is standing now right in the glare of public attention, and she must not get into the papers. I have advised her that it will be better that she say nothing at present, at least, to reporters. I think that the Journal will print what I say upon the verdict, when I state that I think justice has been done promptly. More than that, the jury has freed an innocent woman.”

“Well, did you anticipate such a finding, Governor, or did you look for a disagreement?”

“One can’t always tell what to expect from a jury, but I think we had a very good jury in this case.

“Halloa,” he continued. “Why, they have got the news up in Springfield already,” said he as he read congratulations from his son-in-law, Mr. Herbert Wright of Springfield, from a telegram put in his hand soon after five o’clock.

Remarkable Lot of Letters

“Do you know,” said the Governor, “it’s a very odd fact, but since my connection with this case and the beginning of this trial I have received as many as 50 letters from as many different writers, each one of whom wishes to confess to the fact that he killed Mr. and Mrs. Borden and that Lizzie is innocent.”

“Yes,” said a juror, “our foreman since he got out found a letter of the same sort awaiting him in his box.

“I got a parcel the other day, all rolled up in a round cylinder, and when I opened it there was a hatchet handle that had been broken off from some hatchet. Of course, it didn’t correspond nor fit the celebrated hatchet, so I suppose somebody sent it as a joke; but this morning I got a box package which I haven’t opened yet, but by shaking it I am sure it must contain a hatchet head.”

Juror Swift pressed up to the Governor to tender the best wishes of the jury. “Do you want another hatchet, Mr. Smith?” said the Governor, with that rare smile of his. “Thank you, thank you,” was the juror’s reply. “We think we have had about all the hatchets and axes that we could possibly wish for,” and then everybody laughed, the women joining heartily.

They do say that it was the Governor’s smile that got the verdict, and an irreverent New Yorker declared that it was better than a cocktail. Every morning, when Governor Robinson came in, he never forgot to smile beneficially on the twelve.

Col. Adams’s Belief

Mr. Melvin O. Adams said: “All that I wish to add is that this verdict, not guilty, means not only what it says, but it means the establishment of the innocence of Miss Borden. It can’t be taken in any other sense.

“Didn’t Lizzie say those words to the jury prettily now?” he added, his face lighting up with one of those rare magnetic smiles which vie with those of the foreman in their enticing attractiveness. “You may say that I am now through with the Borden case and ready to turn my hands to something else. As to anticipation, you never can tell what to make of a jury; so I never cease to worry till I am sure they are with me. I haven’t felt for some time that there would be a conviction – that is all I can say.”

Sheriff Kirby Changes His Rig

Sheriff Kirby, Lizzie’s special custodian and guardian through the trial, leaped for the last time from the little black coupe in which both have ridden back and forth for ten days past between the little jail and the Courthouse, and was back again in a trice with a handsome silver-mounted, roomy, black landau, drawn by the Sheriff’s special pets, a splendid pair of black horses. Into the carriage stepped Lizzie and Emma Borden and Mr. and Mrs. Holmes. Mr. Kirby held the bright new ribbons himself, and crack went the whip and away rolled the stylish turnout bound for Fall River.

Just as the horses started the reporters, telegraphers, operators, typewriters and messenger boys rallied quite a little throng around the landau. There was a shout. “Now, boys, three cheers for Lizzie Borden!” And they were given with a will and followed by three more for Governor Robinson. The carriage went first to the jail where Lizzie bade goodbye to her kind friends there and brought away her Thackeray and Dickens. The jail yard was filled by interested neighbors, and here again another round of cheers were given for Lizzie Borden’s return to liberty and vindication.

Here is a transcription of this article:

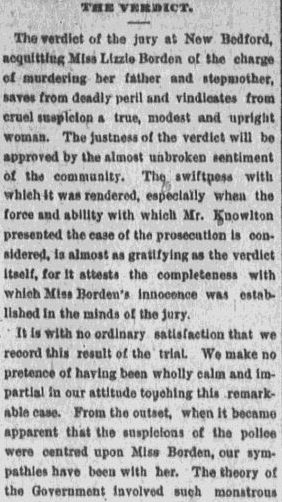

The Verdict

The verdict of the jury at New Bedford, acquitting Miss Lizzie Borden of the charge of murdering her father and stepmother, saves from deadly peril and vindicates from cruel suspicion a true, modest and upright woman. The justness of the verdict will be approved by the almost unbroken sentiment of the community. The swiftness with which it was rendered, especially when the force and ability with which Mr. Knowlton presented the case of the prosecution is considered, is almost as gratifying as the verdict itself, for it attests the completeness with which Miss Borden’s innocence was established in the minds of the jury.

It is with no ordinary satisfaction that we record this result of the trial. We make no pretence of having been wholly calm and impartial in our attitude touching this remarkable case. From the outset, when it became apparent that the suspicions of the police were centered upon Miss Borden, our sympathies have been with her. The theory of the Government involved such monstrous and incredible wickedness in the prisoner as to make its acceptance revolting to every humane instinct. That the accused person was a woman, that she had led hitherto a blameless and useful life, and that the victims of the tragedy were her own parents were reasons sufficient to enlist sympathy with her; and to these reasons were added the pertinacity savoring of persecution with which the Fall River police, once possessed of their theory, bent all their energies to securing her conviction. The ordinary rules of decorum, which forbid the expression of opinion while a cause is pending, were suspended in this unusual case, and the guidance of popular judgment in right channels became a duty, in view of the flood of malignant calumnies to which the prisoner was subjected. Nothing can efface from her memory these ten dreadful months of grief, suspicion and imprisonment, and no recompense can be made her for all that she has passed through; but she passes from the New Bedford courtroom into the light of day a free woman, relieved and vindicated.

It would be difficult to speak in terms of too high praise of the dignity, courtesy and fairness of the court proceedings. If the State suffered in reputation by the extraordinary character of the star-chamber inquisition which initiated the prosecution, the conduct of the case in its later phases has gone far to redeem it. The Judges, the counsel and the jury have performed their duties with the seriousness and gravity which such a case demanded.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

George Dexter Robinson founded the law firm Robinson, Donovan in Springfield, Massachusetts. Today, it is one of the largest law practices in Western Massachusetts. Robinson is buried in Fairview Cemetery, Chicopee, Massachusetts. His memorial can be seen at Find-A-Grave: http://bit.ly/2snKV0v.

I honestly believe she did in fact kill her father and step-mother. But I also believe it was done because of severe abusive behavior toward her by both, and by her actions as she got older I think a mental disorder played a part. Everyone was so overjoyed when she was found innocent, but she was looked at as possibly guilty. She was never accepted in upper society.

I wonder if we’ll ever know for certain? Thanks for writing us.