Introduction: In this article, Duncan Kuehn shares an old newspaper article she found recently while doing family history research, which presents one man’s discovery in 1941 about the meaning of Christmas. Duncan is a professional genealogist with over eight years of client experience. She has worked on several well-known projects, such as “Who Do You Think You Are?” and researching President Barack Obama’s ancestry.

While doing some family history research recently in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, I ran across an article written by Channing Pollock in 1941.

His article is so wonderful that I transcribed every word to share with our readers.

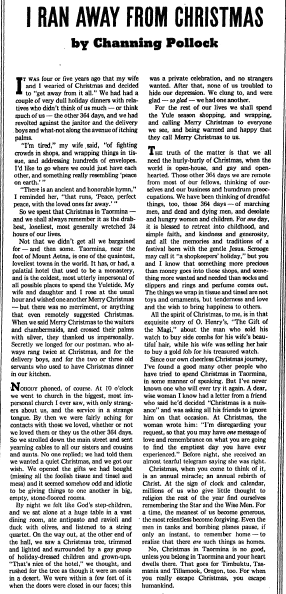

I Ran Away from Christmas

By Channing Pollock

It was four or five years ago that my wife and I wearied of Christmas and decided to “get away from it all.” We had had a couple of very dull holiday dinners with relatives who didn’t think of us much – or think much of us – the other 364 days, and we had revolted against the janitor and the delivery boys and what-not along the avenue of itching palms.

“I’m tired,” my wife said, “of fighting crowds in shops, and wrapping things in tissue, and addressing hundreds of envelopes. I’d like to go where we could just have each other, and something really resembling ‘peace on earth.’”

“There is an ancient and honorable hymn,” I reminded her, “that runs, ‘Peace, perfect peace, with the loved ones far away.’”

So we spent that Christmas in Taormina – and we shall always remember it as the drabbest, loneliest, most generally wretched 24 hours of our lives.

Not that we didn’t get all we bargained for – and then some. Taormina, near the foot of Mount Aetna, is one of the quaintest, loveliest towns in the world. It has, or had, a palatial hotel that used to be a monastery, and is the coldest, most utterly impersonal of all possible places to spend the Yuletide. My wife and daughter and I rose at the usual hour and wished one another Merry Christmas – but there was no merriment, or anything that even remotely suggested Christmas. When we said Merry Christmas to the waiters and chambermaids, and crossed their palms with silver, they thanked us impersonally. Secretly we longed for our postman, who always rang twice at Christmas, and for the delivery boys, and for the two or three old servants who used to have Christmas dinner in our kitchen.

Nobody phoned, of course. At 10 o’clock we went to church in the biggest, most impersonal church I ever saw, with only strangers about us, and the service in a strange tongue. By then we were fairly aching for contacts with those we loved, whether or not we loved them or they us the other 364 days. So we strolled down the main street and sent yearning cables to all our sisters and cousins and aunts. No one replied; we had told them we wanted a quiet Christmas, and we got our wish. We opened the gifts we had bought (missing all the foolish tissue and tinsel and mess) and it seemed somehow odd and idiotic to be giving things to one another in big, empty, stone-floored rooms.

By night we felt like God’s step-children, and we sat alone at a huge table in a vast dining room, ate antipasto and ravioli and duck with olives, and listened to a string quartet. On the way out, at the other end of the hall, we saw a Christmas tree, trimmed and lighted and surrounded by a gay group of holiday-dressed children and grown-ups. “That’s nice of the hotel,” we thought, and rushed for the tree as though it were an oasis in a desert. We were within a few feet of it when the doors were closed in our faces; this was a private celebration, and no strangers wanted. After that, none of us troubled to hide our depression. We clung to, and were glad – so glad – we had one another.

For the rest of our lives we shall spend the Yule season shopping, and wrapping, and calling Merry Christmas to everyone we see, and being warmed and happy that they call Merry Christmas to us.

The truth of the matter is that we all need the hurly-burly of Christmas, when the world is open-house, and gay and open-hearted. Those other 364 days we are remote from most of our fellows, thinking of ourselves and our business and humdrum preoccupations. We have been thinking of dreadful things, too, those 364 days – of marching men, and dead and dying men, and desolate and hungry women and children. For one day, it is blessed to retreat into childhood, and simple faith, and kindness and generosity, and all the memories and traditions of a festival born with the gentle Jesus. Scrooge may call it “a shopkeepers’ holiday,” but you and I know that something more precious than money goes into those shops, and something more wanted and needed than socks and slippers and rings and perfume comes out. The things we wrap in tissue and tinsel are not toys and ornaments, but tenderness and love and the wish to bring happiness to others.

All the spirit of Christmas, to me, is in that exquisite story of O. Henry’s, “The Gift of the Magi,” about the man who sold his watch to buy side combs for his wife’s beautiful hair, while his wife was selling her hair to buy a gold fob for his treasured watch.

Since our own cheerless Christmas journey, I’ve found a good many other people who have tried to spend Christmas in Taormina, in some manner of speaking. But I’ve never known one who will ever try it again. A dear, wise woman I know had a letter from a friend who said he’d decided “Christmas is a nuisance” and was asking all his friends to ignore him on that occasion. At Christmas, the woman wrote him: “I’m disregarding your request, so that you may have one message of love and remembrance on what you are going to find the emptiest day you have ever experienced.” Before night, she received an almost tearful telegram saying she was right.

Christmas, when you come to think of it, is an annual miracle: an annual rebirth of Christ. At the sign of clock and calendar, millions of us who give little thought to religion the rest of the year find ourselves remembering the Star and the Wise Men. For a time, the meanest of us become generous, the most relentless become forgiving. Even the men in tanks and bombing planes pause, if only an instant, to remember home – to realize that there are such things as homes.

No, Christmas in Taormina is no good, unless you belong in Taormina and your heart dwells there. That goes for Timbuktu, Tasmania and Tillamook, Oregon, too. For when you really escape Christmas, you escape humankind.

Related Christmas Articles: