Introduction: In this article – the third of three parts – Melissa Davenport Berry concludes her story about a bold and successful privateer who raided British shipping and helped the U.S. greatly in the War of 1812. Melissa is a genealogist who has a blog, AnceStory Archives, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

Today I conclude my story of the War of 1812 privateer Captain William Nichols, from Newburyport, Massachusetts, dubbed by Brits as “The Holy Terror.”

To recap: In part 2 of this story, Capt. Nichols was put in command of the Decatur in 1812, and in an early adventure had to dump much of his firepower overboard to lighten the ship and outrun an enemy.

Even without guns Capt. Nichols was determined to venture on, but the crew did not share his buoyancy and began to conspire in a plot.

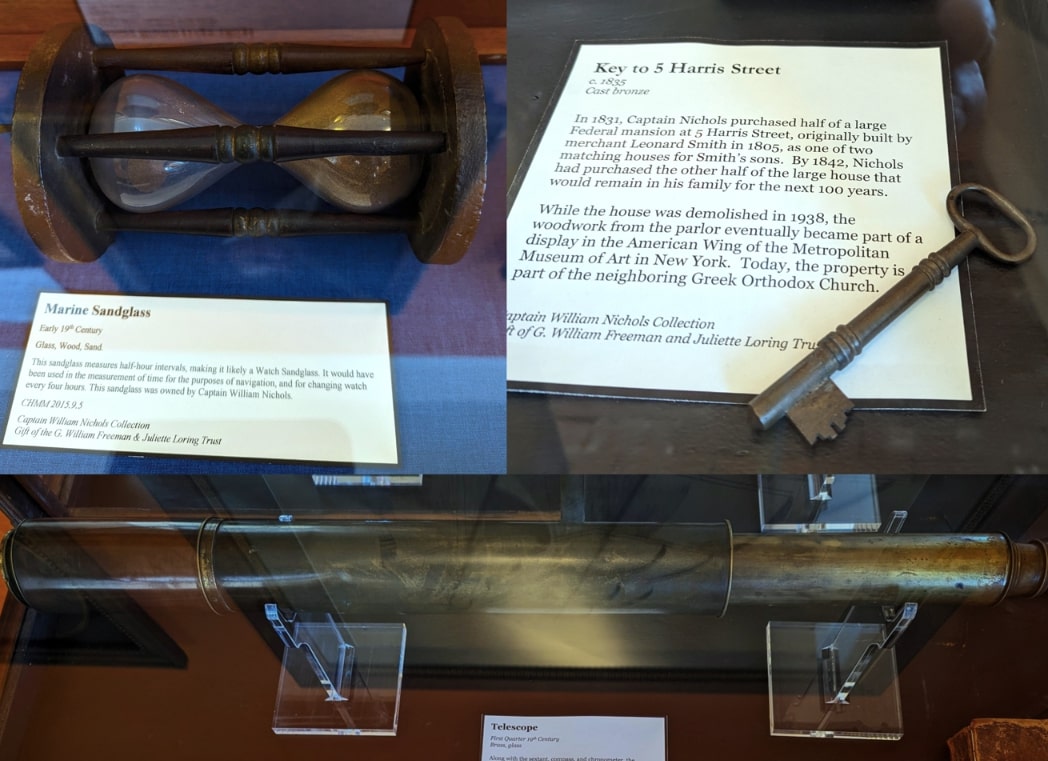

Rev. George Wildes, who published the memoirs of Nichols for the Essex Institute, recalled some of the details which I source below.

Nichols told his insurgent ringleader, “You shall be masters of this brig, or I will.” He then flattened him with a piece of wood to restore order.

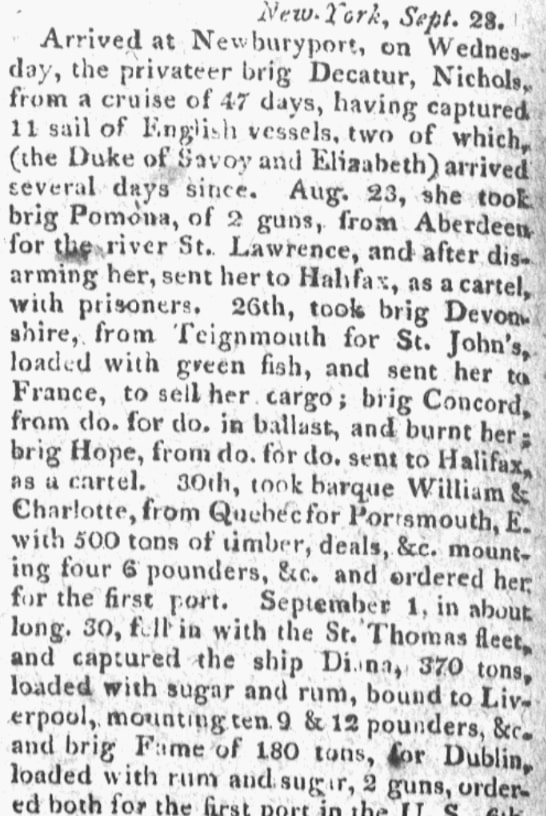

Out of this conflict “rallied some of the bravest spirits of war about him,” and the Decatur went on to capture 11 English ships.

One day they captured the Duke of Savoy, and the following day the Pomona, thus replenishing guns and the crew’s spunk.

A clip from the New Jersey Journal detailed some of Nichol’s prizes which included rum, timber, coffee, sugar, and cotton. Sources say he scored cargo valued at $400,000; one of the biggest was the Diana.

Nichols set a course for home, but the primordial powers were not yet finished with him. His fateful encounter with the British ship Commerce under Captain Watts was a fiery one.

When Nichols asked his remaining crew if they would fight on despite the ominous odds, “three cheers” was the reply, giving a potent surge of panache.

While simultaneously manning his vessel and working the guns, Nichols dodged repetitive gunfire from the Commerce. Capt. Watts directed 14 shots his way, but missed each time, eventually throwing down his musket and swearing: “This man was not born to be shot!”

Decatur arrived back in Newburyport in early October with the vigor of heavy guns and a blazing exposé of 50 flags. No doubt, this Brit vanquisher was a sight for sore eyes!

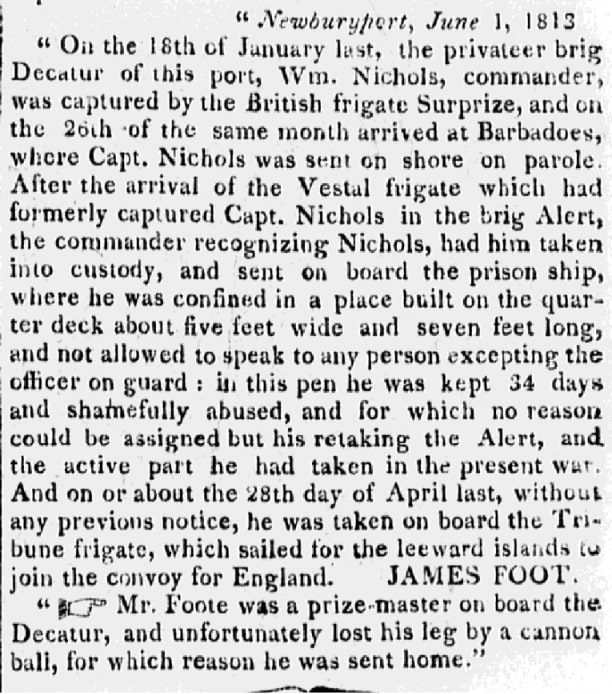

On her second cruise out, the Decatur captured prize after prize, but was eventually taken by the British frigate Surprize and brought to Barbados.

Because of his reputation, Nichols was looked upon initially with high regard and respect. He was a parolee, rather than a prisoner, until another British frigate – the Vestal – showed up.

The Vestal had captured Nichols’ previous ship, the brig Alert, in 1811 before the war officially began – but back then he made a crafty escape and left egg on the face of the British captain (covered in part two) who was now out to even the score.

Here is a statement from James Foot (or Foote), a prize-master onboard the Decatur, published in the Intelligencer about Nichols’ time as prisoner of the Vestal.

James Foot wrote on 1 June 1813:

“On the 18th of January last, the privateer brig Decatur of this port [Newburyport], Wm. Nichols, commander, was captured by the British frigate Surprize, and on the 26th of the same month arrived at Barbados, where Capt. Nichols was sent on shore on parole. After the arrival of the Vestal frigate which had formerly captured Capt. Nichols in the brig Alert, the commander recognizing Nichols, had him taken into custody, and sent on board the prison ship, where he was confined in a place built on the quarter deck about five feet wide and seven feet long, and not allowed to speak to any person excepting the officer on guard; in this pen he was kept 34 days and shamefully abused, and for which no reason could be assigned but his retaking the Alert [back in 1811], and the active part he had taken in the present war.”

Nichols was taken to England and held in a Brit prison until release finally came after negotiations for an exchange.

Nichols returned home, but quickly hit the seas once again in the brig Harpy, with which (according to Rev. George Wildes) he “successfully preyed on enemy ships and brought in rich cargos.”

Although a lion heart roared in Nichols, according to his contemporaries, he possessed a warm disposition and even at sea, both foes and comrades noted his natural graciousness.

After Nichols captured the ship William and Alfred, its master, grateful for the hospitality while imprisoned, extended an invitation to his home in London, should Nichols ever be in the area!

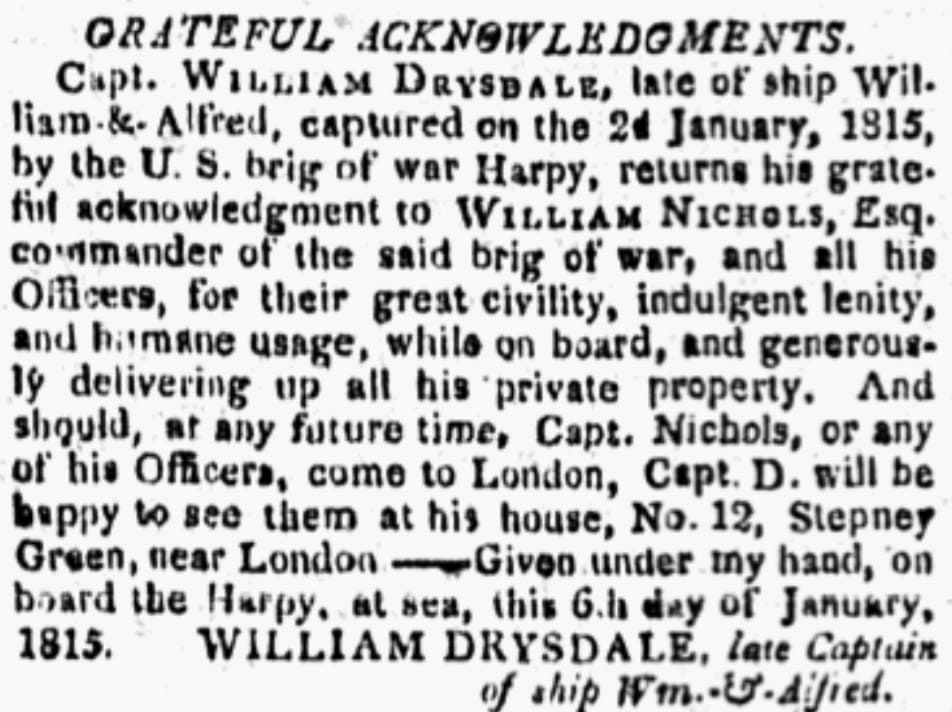

Here is more on this from the Salem Gazette.

This article reported:

Capt. William Drysdale, late of [the] ship William and Alfred, captured on the 2d January 1815, by the U.S. brig of war Harpy, returns his grateful acknowledgment to William Nichols, Esq., commander of the said brig of war, and all his officers, for their great civility, indulgent lenity, and humane usage, while on board, and generously delivering up all his private property. And should, at any future time, Capt. Nichols, or any of his officers, come to London, Capt. D. will be happy to see them at his house, No. 12, Stepney Green, near London.

Given under my hand, on board the Harpy, at sea, this 6th day of January, 1815.

William Drysdale, late captain of ship William and Alfred.

Capt. Benjamin Pierce, owner of the brig Alert which Nichols once commanded, wrote in a letter to Col. Thomas Barclay, the commissioner of prisoners, that Nichols was “modest and unassuming, yet brave and decided;” and “was strictly moral and sincere; as a husband, parent, and neighbor, tender, indulgent, and affable.”

Nichols spent his later years as the port’s Collector of Customs.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Note on the header image: close-up from a portrait of Captain William Nichols, attributed to Charles Delin. Courtesy of Museum of Old Newbury, Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Related Articles: