Introduction: In this article – to help celebrate the Fourth of July – Jane Hampton Cook writes about the figure of Columbia, long used as a symbol for America. Jane, the former White House webmaster for President George W. Bush, is a presidential historian and the author of nine historical books. She is a consultant for the Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commission. Her works can be found at janecook.com.

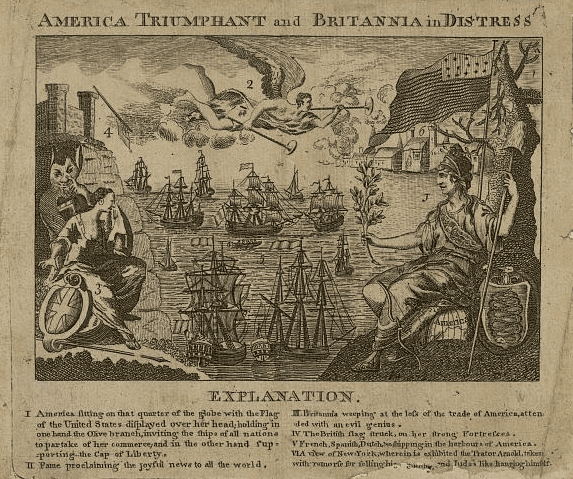

This Independence Day meet America, the aspirational goddess of the American Revolution. The Boston Almanac printed an image of America as a resilient Greek goddess in 1782, while also depicting Britannia as a grieving woman who dropped her trident.

Another name for this goddess was Columbia, who was the subject of many poems during the quest for independence, as a search of “Columbia and 1776” in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives reveals.

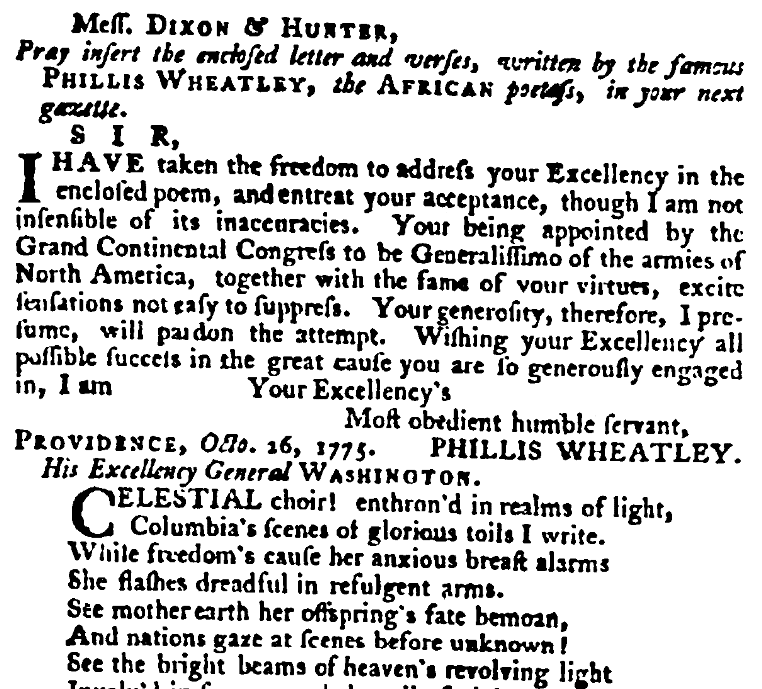

The Virginia Gazette published verses about Columbia from the “Famous Phillis Wheatley” on 30 March 1776. By this time Wheatley had become the first African American published author through a book of her poems.

Arriving as a slave when a young child, Wheatley received an education instead of training as a domestic servant. Eventually freed, she was inspired by the promise of liberty and stopped writing poems about King George III and focused on America instead. She wrote a new poem about Columbia guiding George Washington and sent it to him. Washington loved her verses so much that he wrote her a letter and asked an aide to arrange its publication in newspapers in 1776.

From her poem:

“Celestial choir! Enthron’d in realms of light,

Columbia’s scenes of glorious toils I write.

…Fix’d are the eyes of nations on the scales,

For in their hopes Columbia’s arm prevails.”

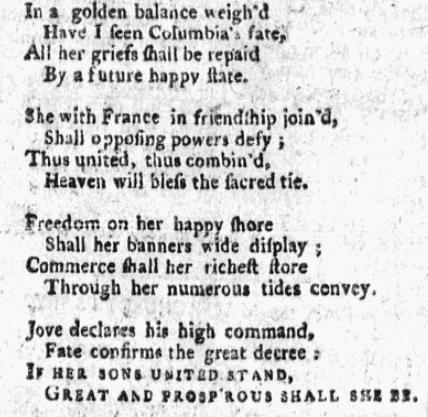

Wheatley was not alone. After America won the Revolutionary War, a flurry of poetry invoked the image of Columbia in 1782, as in this article from the Boston Evening-Post and the General Advertiser on 19 January 1782.

From this poem:

“In a golden balance weigh’d

Have I seen Columbia’s fate,

All her griefs shall be repaid

By a future happy state.”

Philadelphia’s Freeman’s Journal published a poem on 3 April 1782 comparing the masculine English king to a female Columbia, and included the Roman god Jove.

From this poem:

“Now Jove to Columbia his shoulders apply’d.

But aiming to lift her, his strength she defy’d –”

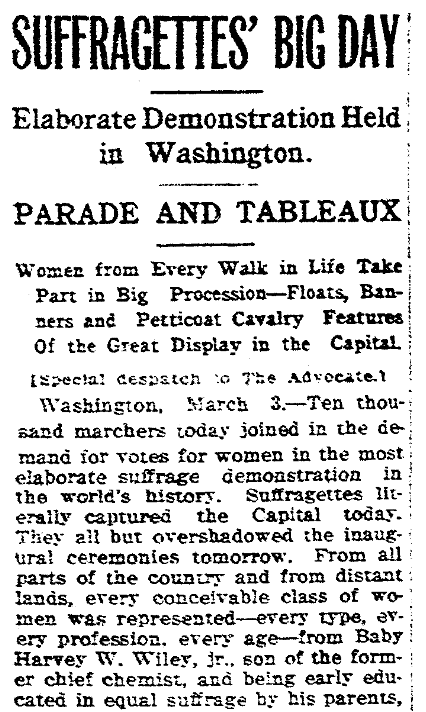

Columbia had a resurgence as an image in 1913, thanks to women activists who tapped her symbolism in the final quest for women’s voting rights. She played a central role in the women’s suffrage parade featuring thousands of women in Washington D.C. in March 1913.

As this article reports:

“As the blast of a bugle died away, Mme. Nordica, famous opera singer and suffragette, attired as ‘Columbia,’ in the national colors and a ‘Liberty cap,’ stepped slowly from the shadows of the giant marble pillars on the porch of the Treasury [building].”

While large U.S. flags unfurled, Columbia was resolute and held a staff topped with an eagle as she performed a skit:

“[Columbia] appeared to hear the approach of the procession – the crusade of women – and summoned to her side ‘Justice,’ ‘Charity,’ ‘Liberty,’ ‘Peace,’ and ‘Hope,’ all represented by prominent suffragettes attired in artistic flowing draperies.”

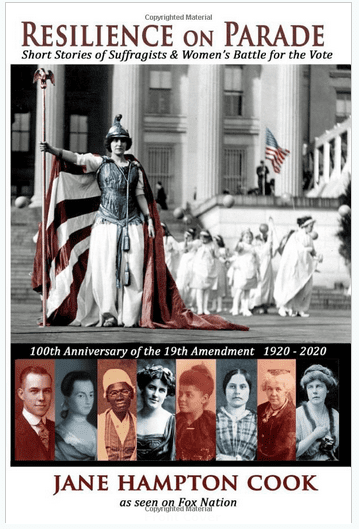

Columbia’s resilient image from the 1913 women’s suffrage parade is the cover art for my new book, Resilience on Parade: Short Stories of Suffragists and Women’s Battle for the Vote.

Columbia’s popularity continued. Her image was depicted on World War I posters in 1917 and as the branding image for Columbia Pictures in the 1920s.

We still see a version of Columbia in the goddess-like Statue of Liberty, which is one of our most popular patriotic symbols and often seen with fireworks on Independence Day.