When most people think of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Apollo missions to the moon, they think of Apollo 11 – which, on 20 July 1969, successfully landed the first humans on the moon. Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin thrilled Americans and the world with their two-hour walk on the moon’s surface while astronaut Michael Collins piloted the command module orbiting above the lunar explorers.

None of that would have been possible, however, without an earlier and in some sense even more historic mission: Apollo 8, which blasted off on 21 December 1968 and successfully became humankind’s first manned mission to the moon.

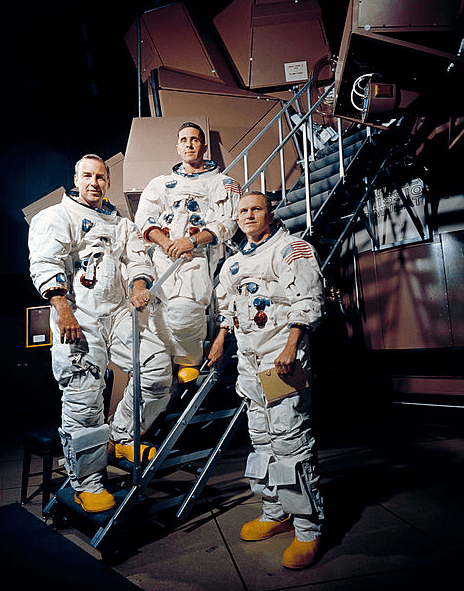

The heroes of Apollo 8 – William Anders, Frank Borman and James Lovell Jr. – performed brilliantly and achieved a staggering list of first-ever achievements.

They were the first humans to leave Earth’s orbit, the first to view the whole Earth, the first to see the dark side of the moon, the first to view and describe the moon’s surface, the first to experience the gravitational pull of a celestial body other than Earth, the first to witness an Earthrise, and the first to return to the Earth after visiting another celestial body.

They also took two of the most iconic and enduring photographs in history: a picture of the Earth as a whole, beautiful round ball in sharp contrast to the blackness of space, and a stunning Earthrise as seen from the moon. Machines had taken similar pictures in the past, but these were the first taken by human beings, and they had the most impact.

Apollo 8 took three days to complete the 235,000-mile journey to the moon. The three astronauts then orbited the moon 10 times during the next 20 hours. Their Christmas Eve television broadcast back to Earth was watched by more viewers than any other show at that point in television history. After six days the mission ended with a safe return, as the astronauts splashed down into the ocean on 27 December 1968. Their mission was a complete success, and made possible the heroics of Apollo 11 the following summer.

These two newspaper articles describe Apollo 8’s launch, filled with marvelous details and a sense of awe.

Here is a transcription of this article:

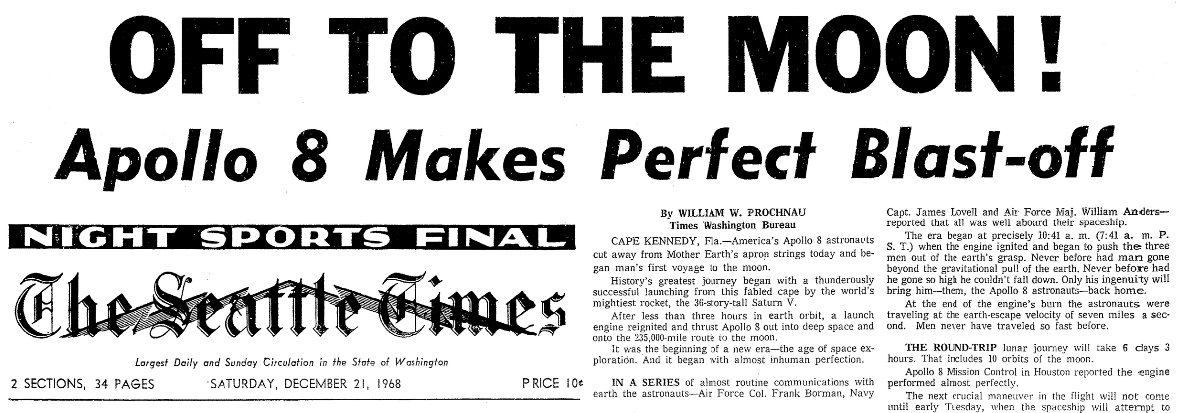

OFF TO THE MOON!

Apollo 8 Makes Perfect Blast-off

By William W. Prochnau

Times Washington Bureau

CAPE KENNEDY, Fla. – America’s Apollo 8 astronauts cut away from Mother Earth’s apron strings today and began man’s first voyage to the moon.

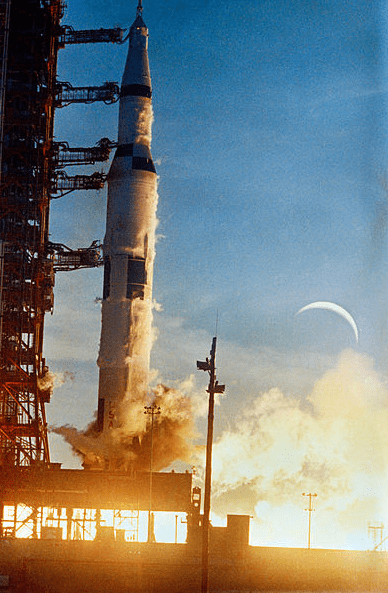

History’s greatest journey began with a thunderously successful launching from this fabled cape by the world’s mightiest rocket, the 36-story-tall Saturn V.

After less than three hours in earth orbit, a launch engine reignited and thrust Apollo 8 out into deep space and onto the 235,000-mile route to the moon.

It was the beginning of a new era – the age of space exploration. And it began with almost inhuman perfection.

In a series of almost routine communications with earth the astronauts – Air Force Col. Frank Borman, Navy Capt. James Lovell and Air Force Major William Anders – reported that all was well aboard their spaceship.

The era began at precisely 10:41 a.m. (7:41 a.m. P.S.T.) when the engine ignited and began to push the three men out of the earth’s grasp. Never before had man gone beyond the gravitational pull of the earth. Never before had he gone so high he couldn’t fall down. Only his ingenuity will bring him – them, the Apollo 8 astronauts – back home.

At the end of the engine’s burn the astronauts were traveling at the earth-escape velocity of seven miles a second. Men never have traveled so fast before.

The round-trip lunar journey will take 6 days 3 hours. That includes 10 orbits of the moon.

Apollo 8 Mission Control in Houston reported the engine performed almost perfectly.

The next crucial maneuver in the flight will not come until early Tuesday, when the spaceship will attempt to brake into orbit around the moon.

The translunar injection burn, the action that thrust the astronauts out of earth orbit, took place somewhere over Hawaii with Apollo 8 headed toward the California coast. Instead of California, the spacemen chose the moon.

The maneuver called for reignition of the launch vehicle’s third-stage engine. It was a tricky and, of course, crucial moment in the flight.

The 5-minute-12-second engine burn began with the spacecraft still in night over the Pacific. Midway through the burn, the astronauts burst into morning.

It was their third sunrise today – and the last, by earthly standards, until they return next Friday.

With the burn completed, Borman, Lovell and Anders were 66 hours 11 minutes from their lunar rendezvous.

The flight, to this point, had proceeded so perfectly that space officials were hard put to discover “problems” to report to the world.

The launching had been made, they said sardonically, 665 milli-seconds late. That is less than one thousandth of a second. The flight, in short, was nearly letter perfect.

Shortly after the astronauts left earth orbit, space officials described the voyage so far in terms ranging from “perfect” to “flawless.”

General Samuel C. Phillips, Apollo director, cautioned that there are “almost six long days of mission ahead of us.” But he said he had “every optimism” now that the journey would be a total success.

Meanwhile, less than an hour after the astronauts jutted out of orbit and toward the moon, they began describing exhilarating sights of the home they were leaving. At an altitude of 10,000 miles, they became the first men to see earth as a disk. They reported viewing an area ranging from the cape they had left to Chile to Gibraltar and West Africa.

“I’m looking out my center window and the window is bigger than the earth is,” Lovell said from 20,000 miles.

At 17,000 miles, Borman fired a brief blast from control rockets to get farther from the Saturn V third stage, jettisoned after it kicked them out of orbit. It was trailing 500 to 1,000 feet behind Apollo 8 – too close for comfort.

The perfect launching came in a litany of thunder and flame precisely on schedule at 7:51 this morning (4:51 Seattle time).

The sound waves, possibly the greatest ever created by man, rolled across the Palmetto Flats and pummeled the nearest observers, three miles away. Much of the sound was too low for the human ear. But if could be felt. It struck the chest in a staccato series of thumps, shaking the viewing stand the way no Florida hurricane ever would.

The rocket, trailing orange flame, lifted agonizingly away from Pad 39-A, climbed above the cape’s sandy waste and arched out over the Atlantic’s armada of shrimp boats plying their trade even on this day.

At liftoff, the rocket weighed 6.2 million pounds, most of this in fuel that was consumed in the first 2½ minutes of flight.

The Boeing-built first stage, eating fuel at the rate of 28,000 pounds a minute, did the early work.

Like a huge firebird, the booster sent Apollo 8 into its long, bending flight over the sea. Still visible to the entranced viewers, the booster disengaged after 150 seconds, looped farther into space and then fell back into the sea.

The giant Boeing booster had taken the spacemen only the first 42 miles of their 235,000-mile journey to the moon. But no 42 miles would be any more important.

The rocket’s second- and third-launch stages also worked perfectly. Visibility was so good that observers could watch the puff of the second-stage ignition even at the distance of 42 miles.

Within 11½ minutes of liftoff, the powerful Saturn V launch vehicle placed Apollo 8 in a 119-mile-high earth orbit.

Borman talked all the way up. “Smooth,” he said. But, later, as the astronauts sailed eastward across the Atlantic, ground control reported that they were “strictly business.”

Orbiting the earth has become routine, perhaps, but not on this trip. The astronauts busied themselves with preparations for the maneuver out of orbit and into the trajectory that would send them to the moon and into history.

Here is a transcription of this article:

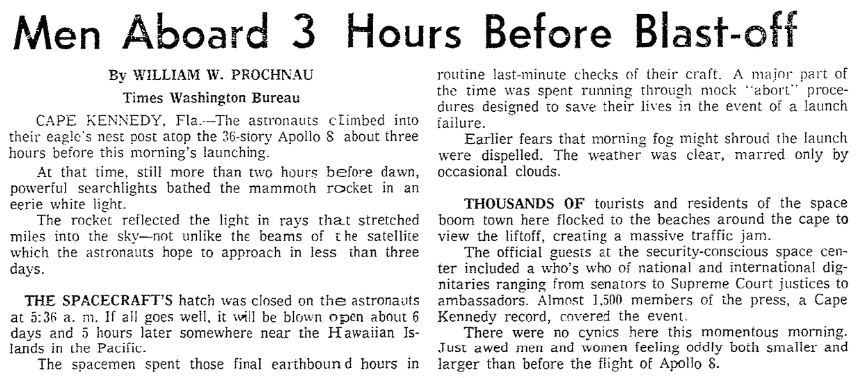

Men Aboard 3 Hours before Blast-off

By William W. Prochnau

Times Washington Bureau

CAPE KENNEDY, Fla. – The astronauts climbed into their eagle’s nest post atop the 36-story Apollo 8 about three hours before this morning’s launching.

At that time, still more than two hours before dawn, powerful searchlights bathed the mammoth rocket in an eerie white light.

The rocket reflected the light in rays that stretched miles into the sky – not unlike the beams of the satellite which the astronauts hope to approach in less than three days.

The spacecraft’s hatch was closed on the astronauts at 5:36 a.m. If all goes well, it will be blown open about 6 days and 5 hours later somewhere near the Hawaiian Islands in the Pacific.

The spacemen spent those final earthbound hours in routine last-minute checks of their craft. A major part of the time was spent running through mock “abort” procedures designed to save their lives in the event of a launch failure.

Earlier fears that morning fog might shroud the launch were dispelled. The weather was clear, marred only by occasional clouds.

Thousands of tourists and residents of the space boom town here flocked to the beaches around the cape to view the liftoff, creating a massive traffic jam.

The official guests at the security-conscious space center included a who’s who of national and international dignitaries ranging from senators to Supreme Court justices to ambassadors. Almost 1,500 members of the press, a Cape Kennedy record, covered the event.

There were no cynics here this momentous morning. Just awed men and women feeling oddly both smaller and larger than before the flight of Apollo 8.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers, as well as more recent events. Do you have memories of the historic flight of Apollo 8? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.