With the obvious exception of the Civil War, the Vietnam War was the most divisive war in America’s history. As the war dragged on year after year casualties kept mounting, television brought the horrors of combat into living rooms, and stories of atrocities circulated. More and more Americans took to the streets to protest the war.

For many people, everything about the war was hateful – including the soldiers fighting it. Returning veterans were bewildered, hurt and angry by their reception back home, with taunting demonstrators calling them “baby killers” and other derogatory terms.

Vietnam veterans’ unhappiness was only deepened by the perceived indifference of the federal government, especially the Veterans Administration. Returning vets needed specialized medical care, counseling, and educational and employment assistance. They felt the government, along with the majority of the American public, wanted to forget about the Vietnam War and everything associated with it – after all, it was a war America had lost.

America entered the Vietnam War on the now-discredited “domino theory” that if the communist North Vietnam conquered South Vietnam, then other countries in Southeast Asia would quickly succumb and eventually communism would take over the world. The first American military advisors arrived in Vietnam (then French Indochina) in 1950, and combat units began arriving in 1965. In part due to the persistence of the anti-war movement, in part due to the perception that the war was not winnable, American combat operations ended in August 1973, and North Vietnam’s triumph was crowned by its capture of Saigon in April 1975.

During the fighting, American forces suffered more than 58,000 killed and over 303,000 wounded. Despite their great sacrifice and commitment, American troops didn’t feel honored by the country they returned home to, and their bitterness grew. Finally, some veterans took matters into their own hands. A wounded Vietnam veteran, Jan C. Scruggs, helped form the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, a nonprofit organization to raise money for a memorial for Vietnam War veterans.

Then, in a contest in which 1,421 designs were submitted, 21-year-old Yale architecture student Maya Ying Lin’s entry was selected for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, which was completed in 1982. Veterans groups organized a five-day event that culminated with a parade of veterans and the dedication of the memorial on 13 November 1982.

As the following two newspaper articles show, the controversy and bitterness about the Vietnam War carried over to Lin’s memorial design and the five-day dedication ceremony. This first article was published by the New York Times and reprinted by the Times-Picayune on its front page.

Here is a transcription of this article:

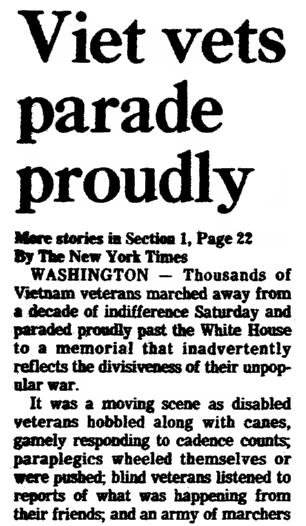

Viet Vets Parade Proudly

WASHINGTON – Thousands of Vietnam veterans marched away from a decade of indifference Saturday and paraded proudly past the White House to a memorial that inadvertently reflects the divisiveness of their unpopular war.

It was a moving scene as disabled veterans hobbled along with canes, gamely responding to cadence counts; paraplegics wheeled themselves or were pushed; blind veterans listened to reports of what was happening from their friends; and an army of marchers and walkers, dressed in everything from baggy fatigues to camouflage suits to full-dress uniforms or sport jackets, moved slowly along majestic Constitution Avenue, waving tiny American flags and raising their fists in triumph.

The march proved a satisfying catharsis for veterans who have long felt themselves a neglected, discarded army – reviled by some as “baby killers,” scorned by others for failing to win, ignored by a public eager to forget an unpopular, nation-splitting war.

The camaraderie was almost palpable as veterans embraced in the streets or locked hands in ritual handshakes. After years of self-doubt and resentment at public indifference, they were staging their own celebration – a coming-out party given by the veterans for the veterans.

But it was not the heroes’ welcome – the ticker tape parade with roaring crowds and an outpouring of gratitude – that many veterans openly long for. Long sections of the viewing stand were half empty, and some blocks along the 10-block parade route had but a single broken line of spectators on each side.

The five-day “National Salute to Vietnam Veterans,” which culminated in Saturday’s march to the new memorial, was designed, according to its chief organizer, Jan C. Scruggs, “to stimulate the long overdue national recognition that has largely been denied to those of us who served in our nation’s longest war.”

But on this raw, blustery morning in the nation’s capital, with winds gusting enough to spill coffee out of cups and put goose pimples on the short-skirted majorettes, there was little indication that any vast segment of the public has rallied to their cause.

Those who did brave the gusts kept up a steady patter of handclapping, punctuated by bursts of louder applause and cries of “Thank you, Indiana, thank you,” or “Yeah, Iowa,” or “God bless you” as the various state delegations passed by.

…But the memorial itself remains an object of controversy. It is essentially a V-shaped wall of polished black marble on which are etched the names of all 58,000 American servicemen who died in the war, arranged chronologically by date of death. Almost from the start, strong supporters of the war have complained that the memorial diminishes those it seeks to honor. The V-shape, they say, is reminiscent of the peace symbol flashed by antiwar protesters. The black color, they say, is too negative. The location of the marble slabs, in a depression on the mall, is, they say, offensively inconspicuous, not like the heroic monuments traditionally associated with war memorials.

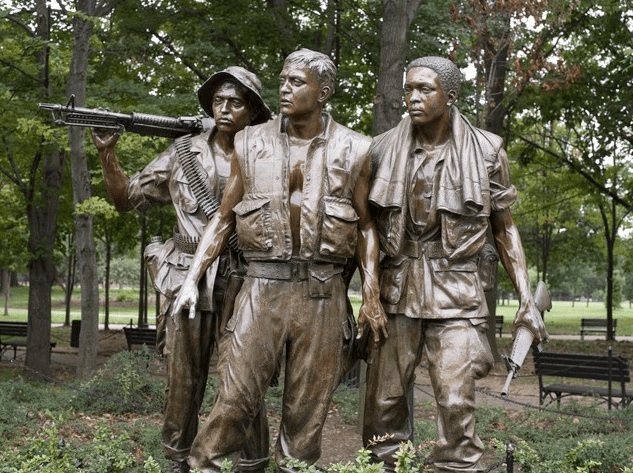

These conflicts were partially resolved by a decision to add a sculpture of three servicemen and a flagstaff next year.

But dissension over the memorial continues to run high, even among the veterans.

“We want a statue and a flagpole, too,” said Donald Sherman, a paralyzed veteran who watched Saturday’s parade from his wheelchair. “The flag is what we fought for, isn’t it?”

But John Beam, an Army artillery veteran from Baltimore, carried a sign opposing the additional statuary because “it will stand in silent approval as we march by on our way to the next war.”

A compromise was reached last month that will result in a statue and a flagpole away from the main focus of the memorial. Its location has not been determined, but it probably will be placed in such a way that it will be seen at the entrance of the site but not from any place near the memorial itself.

Here is a transcription of this article:

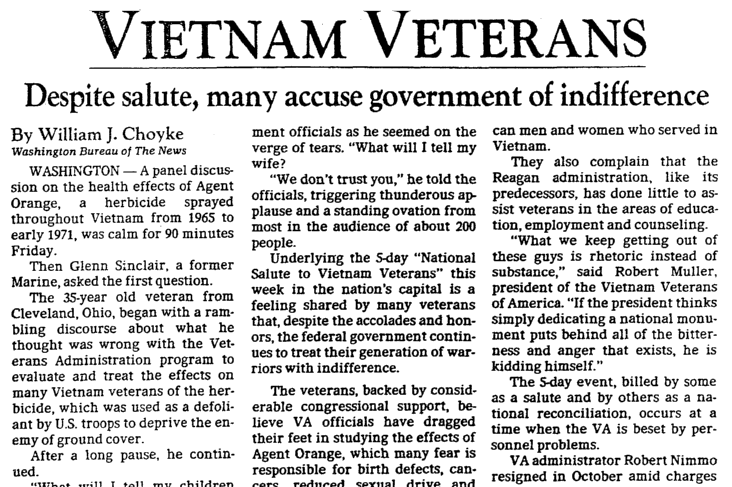

VIETNAM VETERANS

Despite Salute, Many Accuse Government of Indifference

By William J. Choyke

Washington Bureau of The News

WASHINGTON – A panel discussion on the health effects of Agent Orange, a herbicide sprayed throughout Vietnam from 1965 to early 1971, was calm for 90 minutes Friday.

Then Glenn Sinclair, a former Marine, asked the first question.

The 35-year-old veteran from Cleveland, Ohio, began with a rambling discourse about what he thought was wrong with the Veterans Administration program to evaluate and treat the effects on many Vietnam veterans of the herbicide, which was used as a defoliant by U.S. troops to deprive the enemy of ground cover.

After a long pause, he continued.

“What will I tell my children when they want to have kids?” Sinclair asked the panel of government officials as he seemed on the verge of tears. “What will I tell my wife?”

“We don’t trust you,” he told the officials, triggering thunderous applause and a standing ovation from most in the audience of about 200 people.

Underlying the 5-day “National Salute to Vietnam Veterans” this week in the nation’s capital is a feeling shared by many veterans that, despite the accolades and honors, the federal government continues to treat their generation of warriors with indifference.

The veterans, backed by considerable congressional support, believe VA officials have dragged their feet in studying the effects of Agent Orange, which many fear is responsible for birth defects, cancers, reduced sexual drive and other medical problems reported by some of the 2.7 million American men and women who served in Vietnam.

They also complain that the Reagan administration, like its predecessors, has done little to assist veterans in the areas of education, employment and counseling.

“What we keep getting out of these guys is rhetoric instead of substance,” said Robert Muller, president of the Vietnam Veterans of America. “If the president thinks simply dedicating a national monument puts behind all of the bitterness and anger that exists, he is kidding himself.”

The 5-day event, billed by some as a salute and by others as a national reconciliation, occurs at a time when the VA is beset by personnel problems.

VA administrator Robert Nimmo resigned in October amid charges that he improperly used a chauffeured limousine and redecorated his office. This week, 18 senators, including Majority Leader Howard Baker of Tennessee, asked President Reagan to abandon his plan to nominate Assistant Army Secretary Harry Walters to the VA post.

Veterans groups, including the more conservative Veterans of Foreign Wars, repeatedly criticized Nimmo during his tenure for an indifference to veterans’ concerns in general.

Some veterans say the absence at Saturday’s festivities not only of a VA representative but also of President Reagan and Vice President George Bush is reflective of how the administration is giving more lip service than concrete support to veterans.

Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger will represent the administration when the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is dedicated Saturday afternoon. President Reagan is scheduled to be at a memorial service in Chicago for his father-in-law, who died Aug. 19.

Bush left Wednesday on a diplomatic trip to Africa. On Monday, he will attend the funeral of Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev.

The absence of a VA representative is a sad commentary on the state of veterans affairs, said Muller, who is confined to a wheelchair because of war injuries.

“It’s a continuation of a basic indifference to the Vietnam veteran which, believe me, is taken as a slight and insult to my guys,” said Muller, a founder of the organization that claims more than 10,000 members.

The board of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, which raised private money for the monument and organized the bulk of this week’s activities, had hoped to make the $7 million effort non-political.

That desire quickly became wishful thinking.

The monument, designed by Maya Ying Lin, a Yale architectural student from Athens, Ohio, was attacked for failing to symbolize the experience of Americans who fought in Vietnam and was described in some circles as a “black ditch.”

The parade and dedication ceremony Saturday is part of a largely ceremonial tribute organized by the memorial committee, which also included a round-the-clock candlelight vigil in which the names of the dead and missing from the war were read, and an “Entertainers Salute to Vietnam.”

The workshops and discussions Thursday and Friday that focused on employment problems, postwar mental stress and health problems were sponsored by the Vietnam Veterans of America, considered the most activist of the veterans groups.

But even veterans who profess a more conservative philosophy agree with the notion that successive administrations since the United States abandoned Vietnam seven years ago have done little for the newest generation of war veterans.

Dallas real estate agent Tom Hartin had not been involved in veteran issues until this summer, when he heard about the planned national salute. A Vietnam veteran who left the military in 1969, Hartin decided to be part of the effort. He learned that each governor was asked to pick a statewide coordinator.

Gov. Bill Clements, after some delay, designed Medal of Honor winner Roy Benavidez to represent Texas. Hartin called Benavidez to offer his assistance in organizing the state.

Benavidez told Hartin that he thought the designation was an “honorary position” and that he did not realize any work was involved, Hartin said Friday. So Hartin assumed coordinating duties, culminating in the arrival of about 500 Texas veterans for Saturday’s events.

One of Hartin’s first requests was that Clements ask the Texas Veterans Affairs Commission to appoint a representative to assist in statewide organizing.

Hartin said he received a negative response.

“It is just kind of another example of how we are not getting the kind of support we feel we should get,” said Hartin, who estimates he will spend about $3,000 in personal funds in his effort.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand more recent lives and events in American history. Did you or any of your family serve in the Vietnam War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Article:

I think it is the Revolutionary War, not the Vietnam War, that was the 2nd most devisive war in American history. Many residents of the 13 colonies were British loyalists who, during and after the war, lost everything and had to emigrate to Canada or back to Great Britain. While the war was in progress, many loyalist homes were burned and loyalists were tarred and feathered.

You make a fair argument, Chad, and of course there is no right or wrong in this choice. Both wars were divisive; I personally think the Vietnam War was more so, causing deep wounds in this country that still haven’t fully healed.

Yes, it is a toss up as to which war is the second most decisive war in “our history.”

As for the Vietnam war we had far more reporting by both press and television to inform us what transpired somewhat immediately that day on that day. Thus allowing us immediate reactions depending which way we felt about said war. Where as during The Revolutionary War we can only surmise how the people felt by primarily reading either the articles written by the participants of the time or the authors or historians of and after the war explaining or interpreting the war and the impact on this “new” country: USA.

What seems to be missing is another war which had as much an impact on our “history” as any other. That is WWII. Those who born years after it forget how much it impacted us. Fortunately, we had little or few battles in or on “our land/territory. But, if we had not been attacked and while our Congress stressed through legislation to keep us “neutral” as much and as long possible, who knows what the outcome of that war would been and like. Remember, the Germans didn’t want the Japanese to attack the U S and to keep us from helping Great Britain and others. The Germans did NOT want the U S to enter the war as early as we did. Although we were supplying war materialsthrough “Lend-Lease” supplies to GB, numerous American vessels were targeted by Nazi subs, yet our Congress still “tied” FDR’s wants to outright get involved and helped Great Britain more.

What many may not be aware there was “tight” security (censorship) on any reporting of the war: radio, press, and pictures (including movie news). While as most know there was little, if any, censorship of data exiting Vietnam. Because there was no “war” within our borders, a sleeping giant “tiger” was awakened and our war production out stripped what the Axis powers thought we could do.

If we did NOT respond as we did and as early into WWII as we did and were drawn very late into WWII, we can only guess the outcome. Per Nazi Germany’s anticipated plan the U. S. would enter into WWII late enough and Germany would have occupied all of Europe and thus would NOT have Great Britain as a “base” of operation leading to invasion of main land Europe…….