Introduction: In this article, Mary Harrell-Sesniak shows a fun way to get kids interested in genealogy and the past: by looking through old newspapers to learn about some of the codes and ciphers our ancestors used. Mary is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background.

Genealogists dream of ways to engage children and grandchildren in activities that lead to the love of family history.

It’s not that easy. Just reciting the names of earlier family members doesn’t work. If you’re like me, I used to become glazed over when my mother mentioned long-ago people whom I knew I’d never meet. Certain activities, such as dragging the children to cemeteries, works a little better, but not for all. However, as we all know, you only need one family historian at each generation to pass the love along.

The Fun of Discovery

So experiment with activities that lead to discovery – that’s something most children love. One that looks promising is to scour old newspapers for secret codes, with their fodder for young imaginations. Getting children engaged in searching old newspapers builds a skill essential for later genealogy research.

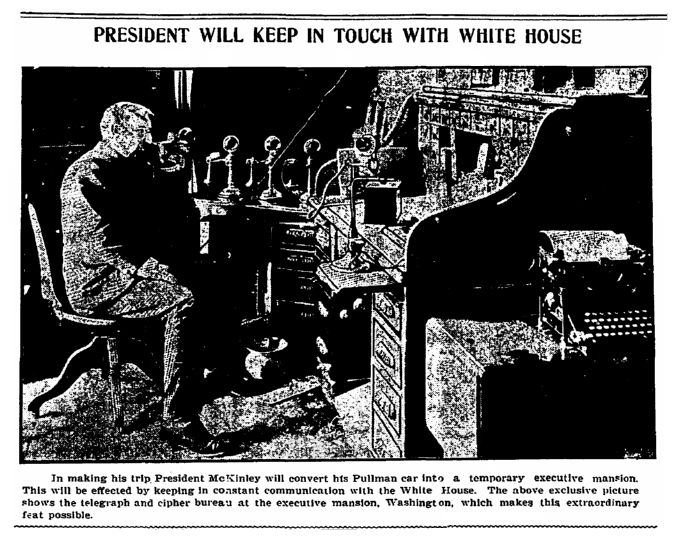

President McKinley’s Secret Messages

Read about how President McKinley sent encrypted messages from his Pullman train car in 1901. He utilized a special telegraph and cipher bureau to keep in constant communication with the White House without outsiders being able to read the messages.

George Washington used secret codes, as did many in the military before and afterward. Search old newspapers, looking to historical eras for ideas – paying special attention to the military’s use of codes.

However, don’t assume that secrets codes were only essential in times of war – they were also used to protect business secrets and inventions from being stolen, and for diplomatic correspondence.

General Trochu’s Method

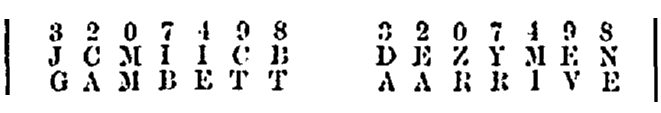

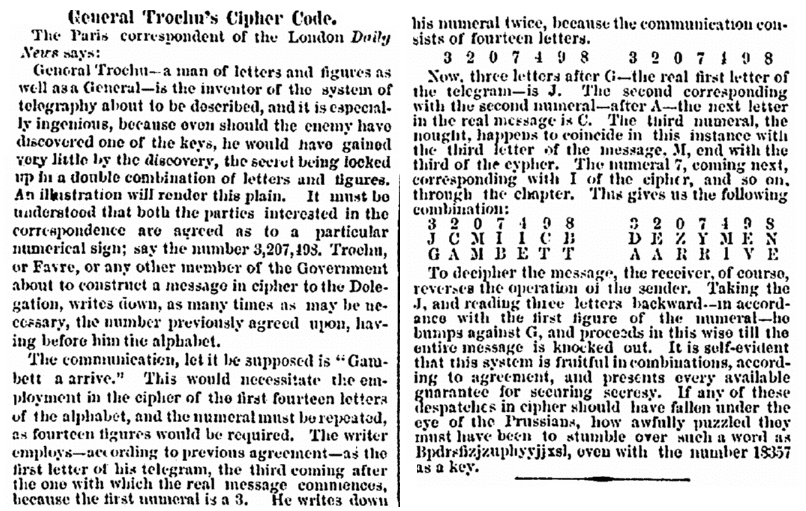

For instance, this coding example – based on a method devised by a Frenchman, General Trochu – was published in an 1871 newspaper article.

A French diplomat in London wanted to alert Paris that a Mr. Gambett had arrived in the English capitol. Using the general’s coding method, the number sequence “3207498 3207498” was used to generate this cryptic message: “JCMIICB DEZYMEN.” When Paris received the message, it was deciphered to read: “GAMBETT A ARRIVE,” French for “Gambett has arrived.”

Can you guess how “JCMIICB DEZYMEN” was decoded to read “GAMBETT A ARRIVE”? It involves a mathematical substitution process which I won’t reveal here. If you don’t figure it out, I provide the answer at the end of this article.

Cipher Cabling

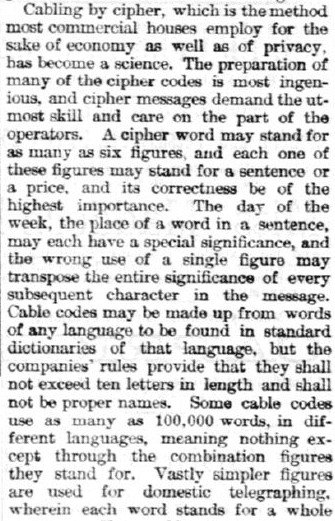

As clever sleuths became better at decoding, methods needed to become more elaborate. This 1887 newspaper article notes that in order to protect trade secrets, commercial houses essentially created elaborate tables. Some had as many as 100,000 words in different languages:

A cypher word may stand for as many as six figures, and each one of these figures may stand for a sentence or a price, and its correctness be of the highest importance. The day of the week, the place of a word in a sentence, may each have a special significance…

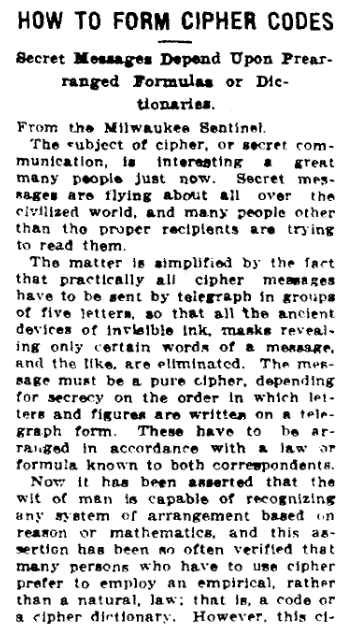

Word Substitution / Jumble Cipher

An alternative method was suggested in this 1915 newspaper article. It works by creating substitution dictionaries that are drawn at random. When done you have a cipher insolvable by any process. As this newspaper article noted, foreign governments were willing to pay as much as $50,000 for a substitution dictionary. With a financial inducement like that, they were certain to get their hands on one and break the code sooner or later.

Briefly, it was created as follows:

- Take 5,000 words and write them on red and blue slips.

- Shuffle the pile of red slips and the pile of blue slips and draw one from each.

- If you find “emperor” on the red slip and “kangaroo” on the blue slip, thenceforth “kangaroo” stands for “emperor.”

- Put the equivalents down in two cipher dictionaries, red-blue and blue-red.

Dual Meanings

There are many more newspaper articles describing ways to encrypt messages, so have fun researching them. However, I have a word to the wise. While querying old newspapers, you’ll note that cipher was not just a term for coding; it also indicated mathematics. Notice this 1747 advertisement for a schoolmaster at John Broughton’s school at Rariton, looking for “a good School-Master for Children, that can teach Reading, Writing and Cyphering.”

General Trochu’s Cipher Code: the Explanation

As promised: if you didn’t figure how “JCMIICB DEZYMEN” was decoded to read “GAMBETT A ARRIVE,” here is the explanation for General Trochu’s method. I’ll leave it for you to read rather than recap the steps, as this newspaper article provides a good explanation.

If you really have a mischievous mind, encrypt old love letters or special genealogy messages using the general’s method. Your descendants will think of you as one of their more memorable ancestors!

Other Ideas to Inspire Young Genealogists

Be sure to inspire the young with family stories, particularly if they have a mysterious component to them. Look up intriguing articles and play a type of “hide and seek” or bingo with the family lore. Offer inducements or prizes for the answers.

- Did grandpa really have a run-in with notorious bank robbers?

- What did grandma win at the county fair?

- What was so funny about the name of your first cousin?

For more fun ideas, I encourage you to reread these earlier blog articles for other inspirations. Use them at your next family reunion or save the ideas for a rainy day!

Related Articles: