Introduction: Mary Harrell-Sesniak is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background. In celebration of Presidents’ Day, Mary takes a look at the last words our first four presidents supposedly said on their deathbeds.

In honor of Presidents’ Day, I decided to research the last words of our first four United States presidents. You’ll find them quoted in books, in historical documents and in historical newspapers.

What I found while researching was intriguing: some of these accounts of presidents’ last words are noteworthy – and others, well (how do I say this politely), may be historically inaccurate.

I’ll let you be the judge if any of the common lore should be discounted.

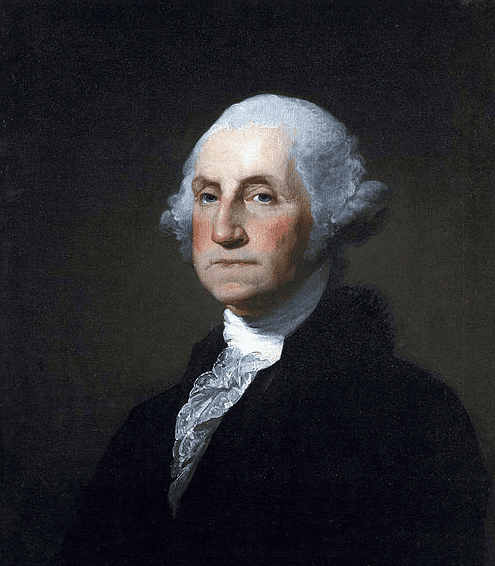

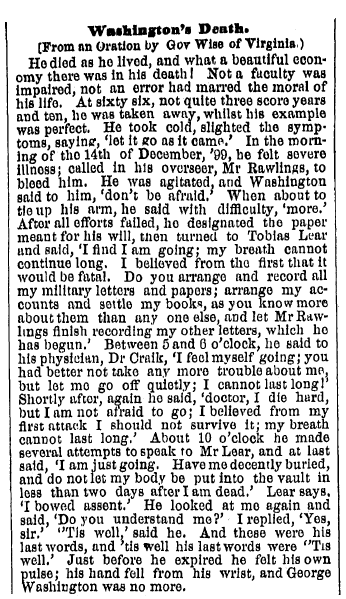

George Washington (1732-1799)

Many, including Mount Vernon’s website, report George Washington’s final words as “’Tis well.”

These final words were said during a conversation with Washington’s personal secretary Tobias Lear, but interestingly, we do not find it recorded in a newspaper until years later. The Springfield Republican in 1856 published a full account of Washington’s last day, which claims a far more extensive report of the last words of George Washington than the Mount Vernon website. Part of this report discusses Washington’s conversations with his physician, and others with his secretary. No family member, including his wife Martha who died in 1802, is mentioned.

The old newspaper article reports that Washington was ill and asked to be bled, which although gruesome by today’s standards, was an accepted medical treatment at that time. His overseer, Mr. Rawlings, was concerned; his hands trembled and Washington told him: “Do not be afraid. More.”

After this, time was spent with his secretary and Washington indicated where his will was. Then he said:

I find I am going; my breath cannot continue long. I believed from the first that it would be fatal. Do you arrange and record all my military letters and papers; arrange my accounts and settle my books, as you know more about them than any one else, and let Mr. Rawlings finish recording my other letters, which he has begun.

Between 5 and 6 o’clock, he addressed Dr. Craik, followed by another sentence not much later:

I feel myself going; you had better not take any more trouble about me, but let me go off quietly; I cannot last long! …Doctor, I die hard, but I am not afraid to go; I believed from my first attack I should not survive it; my breath cannot last long.

His last recorded conversation was with Mr. Lear about 10 o’clock:

I am just going. Have me decently buried, and do not let my body be put into the vault in less than two days after I am dead.

Lear nodded assent and Washington asked: “Do you understand me?”

“Yes, Sir,” he replied, followed by Washington’s final response: “’Tis well.”

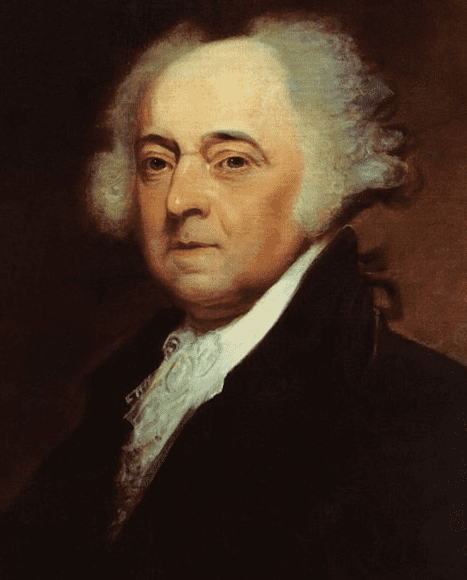

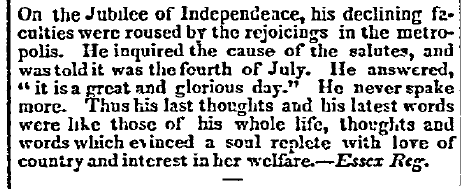

John Adams (1735–1826)

Much has been written about the coincidence of the deaths of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, who both died on the 50-Year Jubilee of the Declaration of Independence on 4 July 1826.

The Jefferson Monticello website reports that the Adams family recalled many years later that ex-President John Adams’s last words were: “Thomas Jefferson survives.” (See Charles Francis Adams, ed., The Memoirs of John Quincy Adams (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1874-77), 7:133.)

Were John Adams’s last words about his friend and the third president, ex-President Jefferson, or were his last words about the 50-year celebration of the Fourth of July? I’m inclined to suspect the Jefferson reference may have been a family joke, since not long after his death, it was noted in the Spectator of 14 July 1826 that Adams’s last words were: “It is a great and glorious day.”

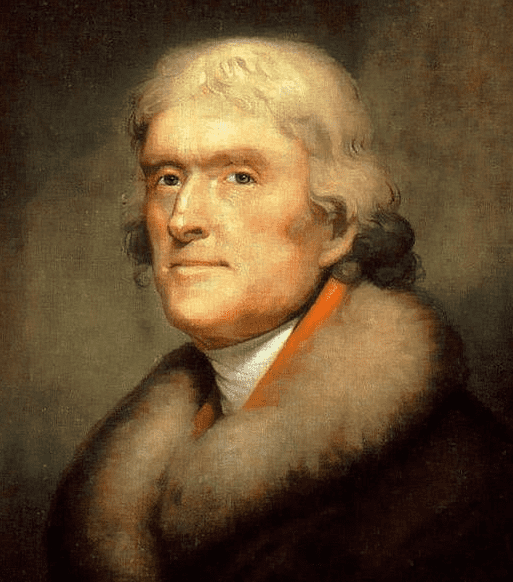

Thomas Jefferson (1743- 1826)

The Jefferson Monticello website reports that nobody can state with certainty what ex-President Thomas Jefferson’s real last words were. Three persons, including physician Robley Dunglison, grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph, and his granddaughter’s husband Nicholas Trist, gave varying accounts of his final words.

Trist reported that on July 3 the last words of Thomas Jefferson were: “This is the Fourth?” and upon not hearing a reply, he asked again. Trist nodded in assent, finding the deceit repugnant.

Randolph reported Jefferson made a strong statement: “This is the Fourth of July.” He slept and upon awaking refused a dose of laudanum (an opiate) by saying: “No Doctor. Nothing more.”

Dunglison’s account stated that the famous last words Thomas Jefferson spoke asked: “Is it the Fourth?” The doctor responded with, “It soon will be.” Several later accounts mention this, but add an additional statement: “I resign my spirit to God, my daughter to my country.”

About 21 years after he passed, the Maine Cultivator and Hallowell Gazette reported an additional variation in 1847: “I have done for my country and all mankind all that I could do, and now I resign my soul to God, and my daughter to my country.”

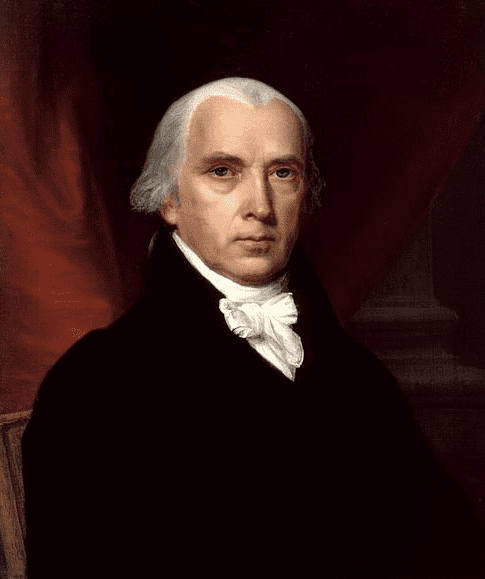

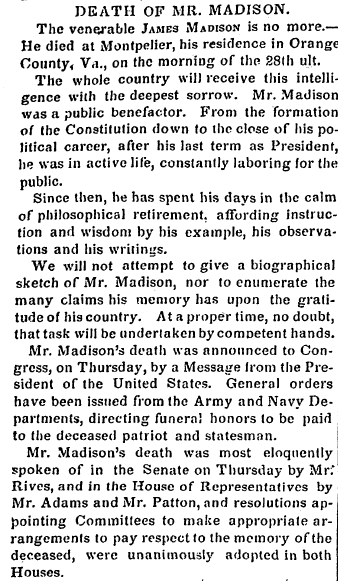

James Madison (1751-1836)

James Madison’s death was only six days prior to the Fourth of July, on 28 June 1836. There is some uncertainty about James Madison’s last words as well, but the common lore is that he spoke last to a niece. She asked, “What is the matter?” Madison’s response was: “Nothing more than a change of mind, my dear.”

However, none of Madison’s obituaries report these – or any other – last words. Typical is this obituary from the Alexandria Gazette.

So there you have it. The authors of historical accounts do not always agree with what people say, especially when it comes to the last words of presidents – but don’t let that stop you from having fun. Search GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives for the last words of U.S. presidents and let us know if you can disprove any of what people say they said!

Related Articles about U.S. Presidents:

[bottom_post_ad]