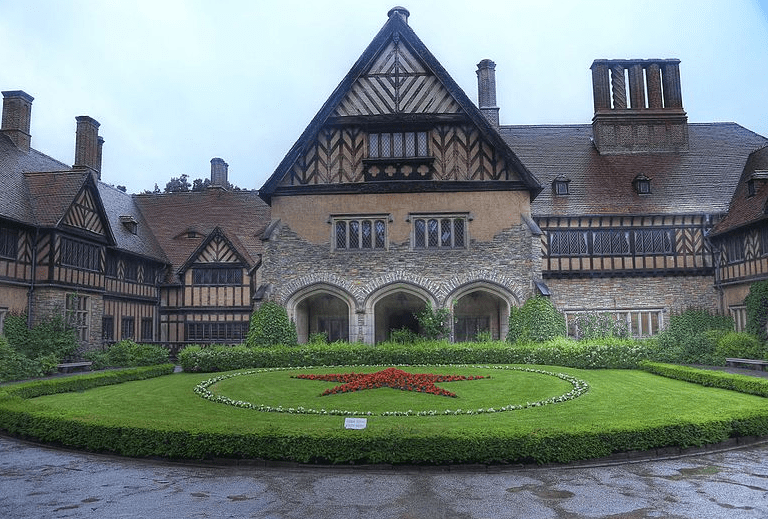

On 16 July 1945, leaders of the “Big Three” allied countries were in Potsdam, Germany, preparing for the next day’s formal commencement of the Potsdam Conference to decide the fate of post-war Germany and Eastern Europe, as well as the ongoing war with Japan and other troubling issues around the world. The United States was represented by President Harry S. Truman, the United Kingdom by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and the Soviet Union by Premier Joseph Stalin.

These three countries had worked together to defeat Nazi Germany – but after winning the war, they now faced the difficulties of forging the peace.

Although still allies, much had changed since the three countries’ last major conference just five months before: the Yalta Conference on 4-11 February 1945. Perhaps most significantly, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had died on April 12, taking with him the relationships he had built with Churchill and Stalin and his ability to smooth over seemingly intractable differences. His vice president, Truman, was now president, and Potsdam was his first international conference.

Churchill, too, was soon replaced. After the Potsdam Conference was underway the result of the U.K.’s general election was announced on July 26, and with the Labour Party’s victory over the Conservative Party, Clement Attlee replaced Churchill as prime minister, removing Churchill’s adroit statesmanship and his distrust of Stalin from the Potsdam equation.

There were other significant changes as well, including the Soviet Union’s occupation of much of Eastern Europe, and the U.S. development of the atomic bomb. However, at important international conferences, where the fate of nations may be decided, decisions often turn on the strengths and weaknesses of the individual leaders.

The following two newspaper articles, printed on the eve of the Potsdam Conference, emphasize this fact.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Truman at Potsdam

The eyes of the world are trained upon Potsdam, where today President Truman will meet Generalissimo Stalin and Prime Minister Churchill for momentous conferences.

During the succeeding weeks matters of extreme moment to Europe, the British Empire and America will be discussed across the conference table. Out of these conferences are expected to come decisions that will shape the destinies of the Old World for years to come, and principally among them will be the establishment of boundaries between nations only recently at war.

The “Big Three” can be counted on to take up immediately the settlement of small nation controversies. One of these is the restoration of complete independence for Iran, to which the United States is definitely committed; and for a political stabilization there that would promote peace rather than threaten war.

Then too, there is the explosive political situation in the Balkans where threatening exchanges between Greek and Yugoslav sources over alleged oppression in Macedonia have occurred. There is an existing fear that the situation might get out of control and flare into a flame that would involve Great Britain, a proclaimed protector of Greece, and Russia, the big power brother of Yugoslavia.

All of these, and many more, are the issues that will confront the “Big Three” when they get down to business in Potsdam. The issues are of vast importance to peace and security and must be handled with an exceptional brand of statesmanship to bring them to a point of amicable adjustment.

The task of President Truman is a difficult one. As the representative of a leading country in the family United Nations he holds a grave responsibility. He is dealing with two crafty statesmen, both of whom have gone through the test before. Every moment of our chief executive and his aides will be watched with the keenest interest on this side.

Note: The following newspaper column was written by famed journalist Dorothy Thompson, who added to her fame as a pioneering woman journalist when she became the first American reporter kicked out of Nazi Germany, in 1934.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Uncertainties of the Conference

By Dorothy Thompson

The Big Three conference that is about to open in Potsdam is considerably more important than the one held in San Francisco [on 25 April 1945 to draft a charter for the United Nations – ed.], for the course of the world is not determined by generalities and overall formulae, but by specific actions. In Potsdam very important and definite political problems have to be solved in agreement. Yet the conference contains political elements of great uncertainty.

The United States and Russia do not know what, in a few weeks’ time, will be the political situation in Britain. Britain and Russia have no experience whatsoever of President Truman and Secretary of State Byrnes. There has been no preliminary conference between Britain and the United States in contrast to the condition of permanent conference which existed between Prime Minister Churchill and the late President Roosevelt.

In all previous conferences the military situation occupied the foreground. Political issues tended to be postponed, or settled in rather ambiguous agreements. Now the European war is over, political issues are preeminent, and every further postponement increases the number of faits accomplis.

A change of government in Britain would, theoretically, lessen the possibilities of friction between the Soviet Union and Britain. Clement R. Attlee is accompanying Churchill in order to make agreements satisfactory to the Labor Party. But every change in government brings in new personalities and new imponderables, and it is doubtful whether Mr. Attlee can fully foresee the results of a victory for his own party. A party in opposition is never the same as a party in power.

The foreign policy of Mr. Truman and Mr. Byrnes, and their negotiation capacities are still an “X.” Mr. Byrnes was at Yalta – but not as Secretary of State. Mr. Truman has never participated in an international conference. Both are pledged to continue the policy of President Roosevelt – though Mr. Truman has said he would not be bound by verbal agreements made by his predecessor.

Mr. Roosevelt made his policy as he went along. He died in a most critical moment, and left no testament or blueprint for his successors.

What we do know is the temperament and general attitude of the President and Secretary of State in the new Administration. Though they may “agree” with Roosevelt and Stettinius they are quite different men.

Mr. Byrnes, for instance, is a logical successor, not to Mr. Stettinius, but to Cordell Hull. In fact, the similarity is striking. Both are Southern Democrats whose experience has been in Congress and the world of politics, and not in the world of business. Both have solid support in the Senate which makes them invulnerable in the Administration. However other men around President Roosevelt might have disagreed with Mr. Hull, Mr. Roosevelt neither could or would have dismissed him. Mr. Byrnes’s position is equally strong. He will not be a satellite in the Presidential solar system, but an equal star, and, for the time being, he is next in line for the Presidency. President Roosevelt was, to an increasing degree during the war, his own foreign minister. Mr. Truman will not be.

President Roosevelt, also, was a much more subtle and versatile personality than his successor, inclined always to fit himself into situations as they arose and finesse his way among his allies. He had unlimited faith in his own capacity to adjust himself and the American policy to each successive change and crisis. He believed less in fixed principles and firm agreements than in the “climate” of human relationships and in his own capacity to steer with the wind in off-reef directions. That was both his talent and his weakness. Neither Mr. Truman nor Mr. Byrnes have that talent, so they must and will try to avoid the weaknesses.

Mr. Roosevelt liked preliminary conferences, because he liked to sniff out which way the wind was blowing. It is interesting that Mr. Truman and Mr. Byrnes have avoided one. Apparently they do not want previous commitments, and are jealous for American independence and freedom of action. As far as I can sense things, after a long absence from home, I expect a more stubborn attitude, a greater insistence on principles and on agreements that would “stand up in a court of law,” less tendency to leave matters to wide interpretation, and insistence on less ambiguity.

Both Mr. Truman and Mr. Byrnes are politicians, who may be presumed to have an eye on the Presidential elections of 1948, and are susceptible to American public opinion. Mr. Roosevelt was a master at making public opinion. They are not. We may expect, therefore, a greater instinct for those constants in the American mind that are essential for the policies of the parties.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in WWII? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.