Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega writes about a law that may have affected your female ancestor by taking away her American citizenship due to her marriage. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

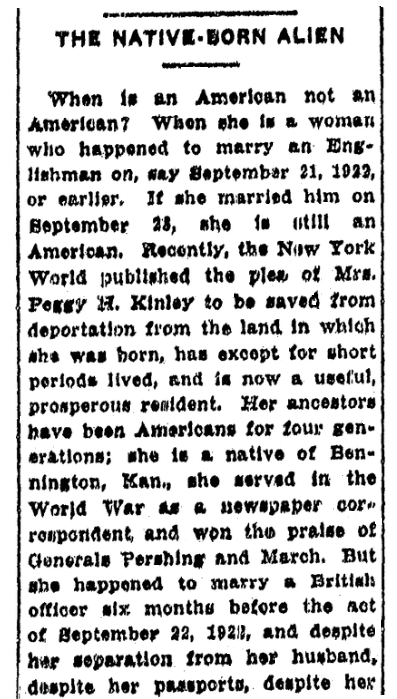

This newspaper article from 1927 asked:

“When is an American not an American?”

The answer:

“When she is a woman who happened to marry an Englishman on, say September 21, 1922, or earlier.”

This head-scratching answer reflects an earlier 1907 law: the Expatriation Act. That law said that when an American-born woman married a non-American citizen, she lost her citizenship and was considered by the U.S. to hold the same citizenship as her foreign-born husband.

American Women’s Citizenship

Prior to 1922, you are less likely to find naturalization papers for a female ancestor. The reason why has to do with derivative citizenship. The idea was that a non-U.S. citizen woman who married a husband who had U.S. citizenship received U.S. citizenship herself as a result of that marriage. If he naturalized, she was included in that naturalization. From 1855 to 1922 immigrant women who married American citizen men became American citizens. But in 1907, the Expatriation Act stated that derivative citizenship would not only affect the immigrant woman, but also the woman who was an American citizen by birth. This meant that American women who married a non-U.S. citizen lost their U.S. citizenship.

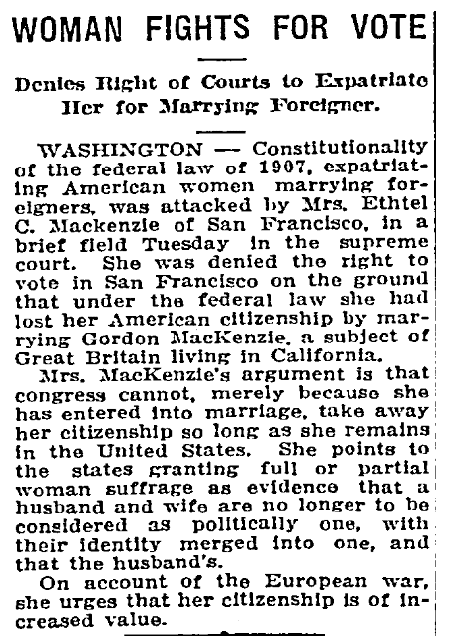

In 1915 the Supreme Court ruled that “marriage of an American woman with a foreigner is tantamount to voluntary expatriatism.” American women who married foreign men and retained their citizenship “would allow them to aid or protect German spies.”*

Now this loss of citizenship may not seem like a problem when weighed against women’s general lack of rights during this time period. But in 1920 when women received the national right to vote, women who had married foreign nationals were not eligible. On top of that, should they travel to other countries they risked not being allowed entry back into the U.S. because of immigration quotas. As women’s citizenship status increasingly related to a denial of legal rights and benefits, the loss of that citizenship was a problem that needed to be solved.

How many women did this law affect? It’s hard to come up with a precise number, but according to Ann Marie Nicolosi’s article, We Do Not Want Our Girls to Marry Foreigners: Gender, Race, and American Citizenship, a look at the 1920 U.S. Census suggests that around 89 of every 1,000 children were born to American mothers and foreign-born men. In the 1910 U.S. Census, nearly six million children had one native-born parent and one foreign-born parent.

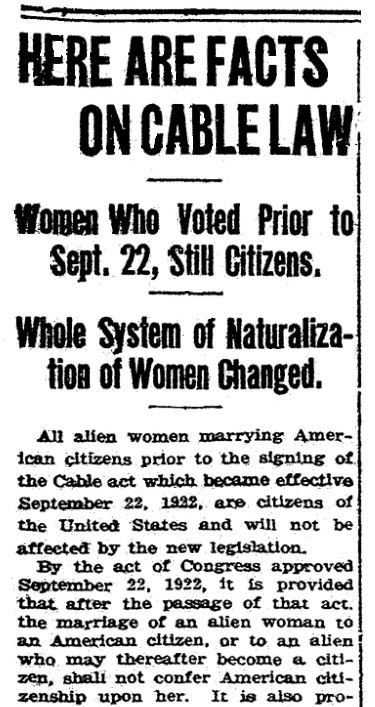

The Cable Act

The 1922 Cable Act signaled the end of women’s derivative citizenship and gave women the right to apply for their own naturalization. The Cable Act, also known as the Married Women’s Independent Nationality Act, was a big step forward – but it would still take additional legislation before all women who had lost their citizenship could be repatriated.

Initially, the Cable Act allowed women who lost their citizenship to go through the naturalization process just as if they were never U.S. citizens. However, this did not include all women. Women who had married men ineligible for citizenship were still not allowed to apply for citizenship.

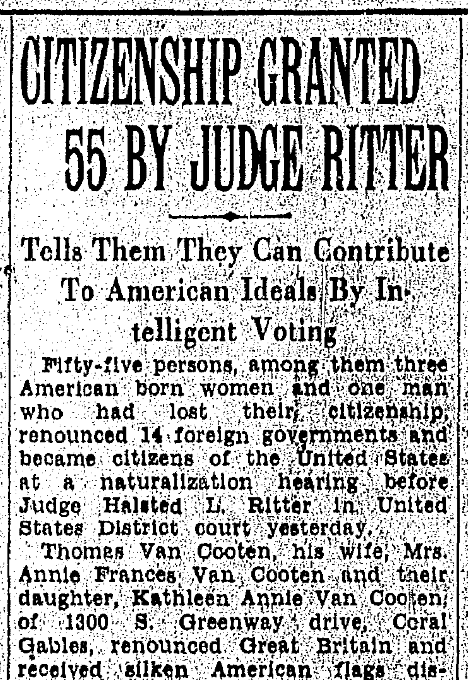

In 1936 women were finally allowed to forgo the lengthy naturalization process and repatriate by taking an oath of allegiance if – and only if – their husbands were dead or they had divorced. It wouldn’t be for another four years, until 1940, when women could repatriate no matter what their current marital status was.

Why Women’s Repatriation?

When I give genealogy talks on the topic of women’s repatriation, I find a few people who are aware of this law because it affected a female ancestor. These family historians may have found out by accident that their U.S.-born ancestress lost her citizenship. My initial interest in this topic began decades ago when I was researching at the Family History Library and found American-born women listed in naturalization indexes. Later I uncovered the story of one of these women while doing some client research.

A few years ago, I began researching at my local branch of the National Archives in my quest to learn more about these repatriations. Since then, I’ve gathered oaths of allegiance from women at the National Archives and other repositories. Probably one of the more surprising lessons I learned is that these women were still repatriating well into the 1970s and beyond!

So, what do the repatriations of women teach family historians who do not have an affected female ancestor? It emphasizes the importance of learning about the current laws for the time and place you’re researching. While you don’t need to go to law school, it can be helpful to know a little about laws that affected our ancestors – like military conscription, homesteading, and naturalization.

The other lesson to take away from this is to be curious. I first learned about a client’s ancestor losing her citizenship by finding her in the 1920 U.S. Census with “Al” written in the immigration column. I wondered what kind of mistake the census taker had made by claiming a woman born in Colorado was an alien. I soon realized the answer. It’s important, when we come across things that don’t seem right, that we follow our curiosity.

Are you curious about laws that impacted your female ancestors? My favorite resource that provides detailed state synopses of laws is the book by Christina K. Schaefer, The Hidden Half of the Family: A Sourcebook for Women’s Genealogy.

Do you have a female ancestor that lost her U.S. citizenship because of her marriage? I’d love to hear her story. Please share it in the comments section below.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

__________________

* “9 Facts about Jeanette Rankin, the First Woman elected to Congress,” Mental Floss (http://mentalfloss.com/article/93596/9-facts-about-jeannette-rankin-first-woman-elected-congress: accessed 14 Spetember 2017).

My Gma, Irish lass, married American guy in 1919. Divorced him 1927. What then was her nationality?

Great question Dan! If your Irish grandma married an American citizen before 1922 she was an American citizen. That’s because women had derivative citizenship until the Cable Act of 1922. Which basically meant that married women shared whatever citizenship their husband’s held. After 1922, married women had to apply for their own US citizenship.

My grandmother was born in Grass Valley, CA, in 1888 and moved to South Africa with her parents in 1898. She met my grandfather, who was born in England in 1883, and we thought that they were married in 1907. We have finally found a marriage cert dated 1917, by which time they had had 4 children and were living out of wedlock. Seems totally out of character. She did have a birth cert. Any ideas on why they waited so long to get married????

Bev,

What an interesting question. I would need more information to even venture a guess. There can be quite a few factors involved in not marrying right away. Money and availability of a nearby minister are a few reasons I can think of. Was one of your grandparents previously married?

It’s not unusual to find that our ancestors had children and lived as a married couple years before actually getting married. Sounds like you have more research to do! Good luck!

Gena

This is fantastic information. It happened to my Great Grandma when she wed her husband in 1917. We discovered this upon her son’s death in 2017 (he never knew — the repatriation papers were buried in a box of “stuff”). I am NOW in the process of writing my thesis for my MA in history on this subject.

Amy, What a find! I’d love to hear more about your research and thesis.–Gena

My grandmother lost her citizenship when she married my grandfather in 10/1921. She and her parents were all born in Michigan. My grandfather, a Canadian, had served honorably in the U.S. Army during WWI. She finally went through the naturalization process in 1940.

Thanks for sharing your grandmother’s story Cynthia.

My grandmother was born in Manhattan, New York City, in 1897. In around 1918, she married my grandfather who had been born in Germany and had lived in the United States since around 1918. In 1926, they traveled with their young son to visit family in Germany, and when they were to return home, they were made to travel as “Alien Passengers.” No nationality was listed on the ship’s manifest for my grandfather, my infant uncle was shown to have correctly been born in the United States, and my grandmother’s nationality was listed as German! By the 1930 census, however, her correct birth place of New York City was listed. (Whether she had to prove this or just tell the enumerator her immigration status, I do not know.) I had heard stories she had to become a naturalized citizen. I cannot find the record showing this naturalization. I know she voted throughout my childhood, so I believe she had to have been a citizen by the 1960s. At the time of their passage to Germany, my grandmother lived in New Brunswick, NJ. Where can I find her naturalization documents? Thank you.

Kathleen, while your grandparent’s trip to Germany was after the passage of the Cable Act she may not have tried to naturalize yet. In fact she may not have realized she wasn’t a US citizen. But without naturalizing she was indeed a German citizen according to the US since she married during the time that women derived citizenship from their husbands.

Prior to 1936 she would have had to go through the naturalization process, after she could have taken an oath if she was divorced or widowed. However, after 1940 any woman, regardless of her marital status could take the oath which meant they didn’t have to go through a lengthy naturalization process. These oaths can be found at NARA. You would need to consult the NARA that has repatriation records for where she lived (most likely NARA at New York City). They should be a part of RG 21. I have seen women repatriating using those oats well into the 1970s.

You might want to look through some online naturalization record collections to see if you find a naturalization record for her. (Have you found your grandfather’s naturalization?)

If you don’t find a naturalization, contact NARA. They may have an index for that Record Group. I’ve also found those repatriation records at a county archive.

Just another twist…even though she voted, that doesn’t necessarily mean she naturalized or repatriated. Many of these women didn’t know they lost their citizenship, and they didn’t have any identification showing they weren’t a citizen. So it wouldn’t be unusual to find someone voted.–Good luck!

I just read about this act and it immediately triggered my memory. My grandmother was born in New Hampshire in 1899 and married my grandfather in 1918. My grandfather was born in Canada but was working and living in the U.S. I remember my grandmother telling me years ago that she lost her citizenship when she married my grandfather and had to get naturalized. I checked U.S. Census records and my grandfather was still listed as an alien in 1920 and 1930 but the 1940 Census said he had completed his first papers, so I assume he was in the process of becoming a citizen then… My grandmother’s status is not noted. How can I find their naturalization records or my grandmother’s repatriation records? They lived in northern New Hampshire. At that time, many people came to this area to work in the paper mills or the woods, and I suspect my grandmother’s experience was not unique.