Introduction: In this article, Jane Hampton Cook describes how President Franklin Roosevelt, eight days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, placed special emphasis on celebrating the first Bill of Rights Day on 15 December 1941. Jane is a presidential historian and author of ten books, including Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. Her works can be found at Janecook.com. She is also the host of Red, White, Blue and You.

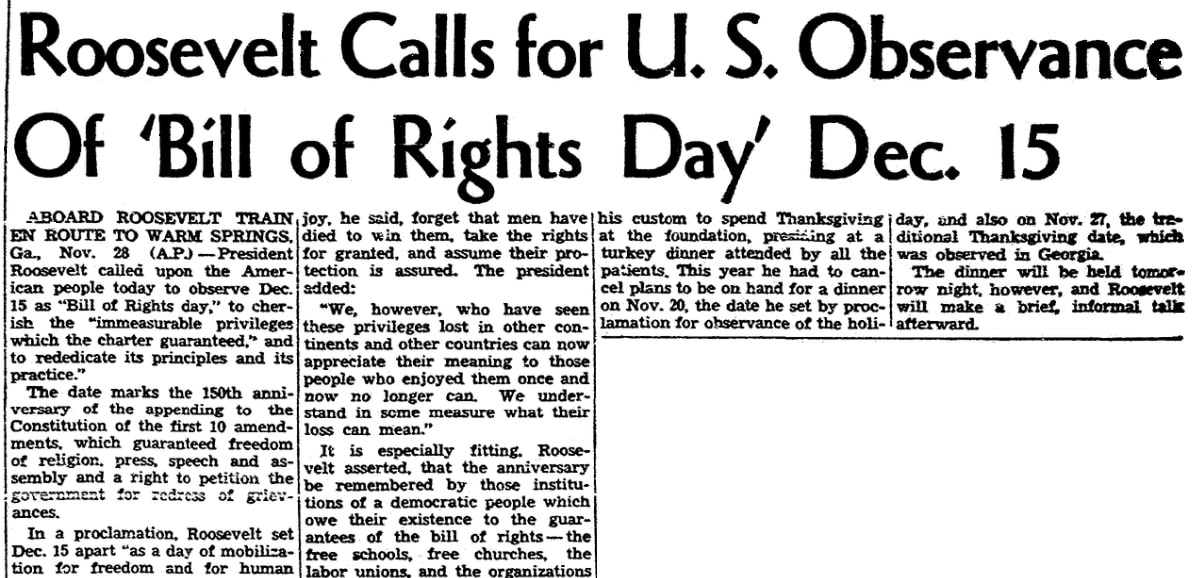

While on a train headed to Warm Springs, Georgia, for a late Thanksgiving holiday on 29 November 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) called upon the American people to observe December 15 as Bill of Rights Day.

According to this article from the San Diego Union, Roosevelt issued a proclamation for Dec. 15 to be set apart:

“as a day of mobilization for freedom and for human rights, a day of remembrance of the democratic and peaceful action by which these rights were gained, a day of reassessment of their present meaning and their living worth.”

Roosevelt’s proclamation further stated:

“Those who have long enjoyed such privileges as we enjoy forget in time that men have died to win them. They come in time to take these rights for granted and to assume their protection is assured. We, however, who have seen these privileges lost in other continents and other countries can now appreciate their meaning to those people who enjoyed them once and now no longer can. We understand in some measure what their loss can mean.”

Roosevelt’s presidential proclamation followed an August joint resolution of Congress calling on the president to designate December 15 as Bill of Rights Day. Government buildings were to display the flag and the American people were to observe the day with ceremonies and prayer.

In its article, the San Diego Union made an interesting observation. Roosevelt’s press secretary and appointment secretary both joined the president for his holiday to Warm Springs, which was not a typical practice: “Usually they go along on trips only when something important may develop.”

The newspaper noted that there was a chance that Roosevelt’s trip “might be cut short because of the Japanese situation and conditions in the Far East.”

At the time, Roosevelt was in communication with Japan’s top diplomat to discuss peace in the Pacific. Roosevelt returned to Washington on December 2 as planned.

Five days later, the Japanese military attacked U.S. ships, aircraft and service personnel at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Newspapers across the country blasted the word “infamy” in their headlines. Like their many counterparts in the press, the New Orleans Item reported the president’s speech to Congress after the Japanese surprise attack.

This article reported Roosevelt’s opening lines in his speech:

“Yesterday, December 7, 1941 – a date which will live in infamy – the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the empire of Japan. The United States was at peace with that nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific.”

In response to the president’s speech, this article reported:

“Congress declared war on Japan today after hearing a stirring indictment of Japanese ‘infamy’ by President Roosevelt. Meanwhile the White House listed the toll in the attack on Honolulu at 1,500 killed, [and] as many more injured.”

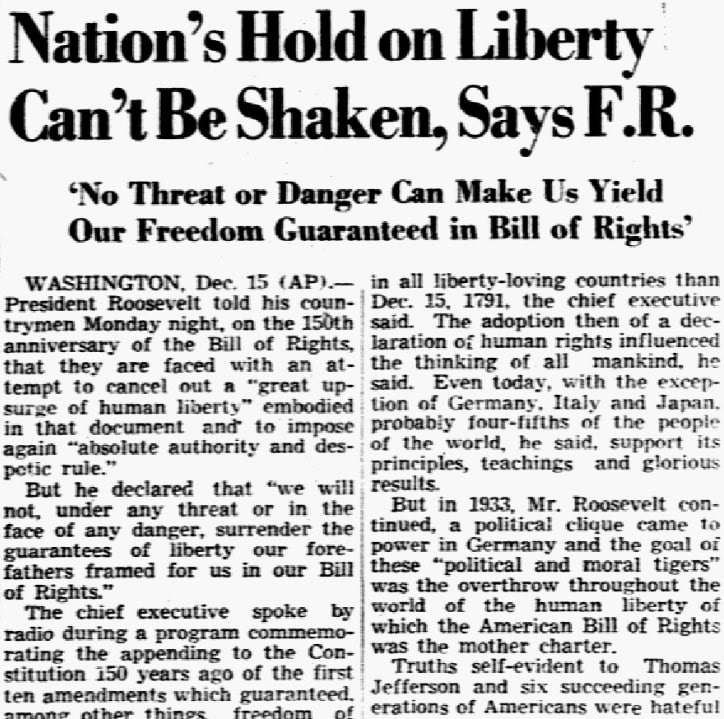

Eight days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, FDR spoke during a radio program commemorating the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights on 15 December 1791. As this article in the Dallas Morning News revealed, his passion was greatly amplified because America was now at war. His language was stronger and more animated. His tone was fierce.

This article quoted the president as saying:

“What we face is nothing more nor less than an attempt to overthrow and to cancel out the great upsurge of human liberty of which the American Bill of Rights is the fundamental document; to force the peoples of the earth, and among them the peoples of this continent, to accept again the absolute authority and despotic rule from which the courage and the resolution and the sacrifices of their ancestors liberated them many, many years ago.”

He promised to preserve liberty once again and noted that the adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791 influenced the thinking of all humankind. He derided the “political and moral tigers” of Germany led by Adolf Hitler who sought to overthrow human liberty throughout the world.

The Milwaukee Sentinel printed even more details from Roosevelt’s speech marking the anniversary of the Bill of Rights.

According to this article, Roosevelt said in his speech that Hitler had proposed a doctrine:

“That the individual human being has no rights whatever in himself and by virtue of his humanity; that the individual has no right to a soul of his own, or a mind of his own, or a tongue of his own, or a trade of his own; or even to live where he pleases or to marry the woman he loves; that his only duty is the duty of obedience, not to his god, and not to his conscience, but to Adolf Hitler.”

Though conceived as an observance before the attack at Pearl Harbor, the first official Bill of Rights Day on 15 December 1941 turned into an opportunity for Roosevelt to throw down the gauntlet for universal human liberty across the globe:

“We will not, under any threat or in the face of any danger, surrender the guarantees of liberty our forefathers framed for us in our Bill of Rights.”

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in WWII? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Note on the header image: Photo of President Franklin D. Roosevelt signing the declaration of war against Japan, in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, 8 December 1941. Credit: National Archives and Records Administration; Wikimedia Commons.

Related Articles: