Introduction: In this blog article, Mary Harrell-Sesniak shows how old newspaper articles can help your genealogy research by fact-checking statements made by authors and researchers. Mary is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background.

It’s always fascinating to fact check what people say happened in the past. Many authors and researchers are historically accurate, but some make statements that don’t hold true.

One such statement often repeated was that newspaper editor Horace Greeley famously said “Go West Young Man.” But did he really invent this phrase?

In 2012, I discussed this in a GenealogyBank Blog article: Fact or Myth: Did Horace Greeley Really Say ‘Go West Young Man’? Turns out the statement was taken out of context, and that Greeley wasn’t even the first to say it.

So as any diligent genealogist should do, I make it a practice to recheck author statements.

This is an essential genealogical skill – always try to set the facts straight when others claim otherwise. As an added bonus, your research may uncover tidbits, treasures and other nuances that well-meaning historians and genealogists have overlooked. Here are some examples I found using GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives.

Benjamin Franklin

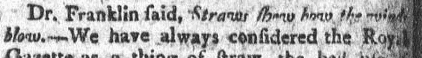

Most are familiar with Benjamin Franklin and his “Poor Richard” proverbs, but if you search old newspapers you’ll find some proverbs that most people don’t know about.

For example, search the Web for “straws show how the wind blows” and you’ll find vague references to the quote. If you search historical newspapers, however, you’ll find an attribution to Franklin published in this 1801 newspaper article. In all fairness, I can’t determine if he was just quoting an ancient saying, but this author writes as if it were unique to Dr. Franklin.

Walt Whitman

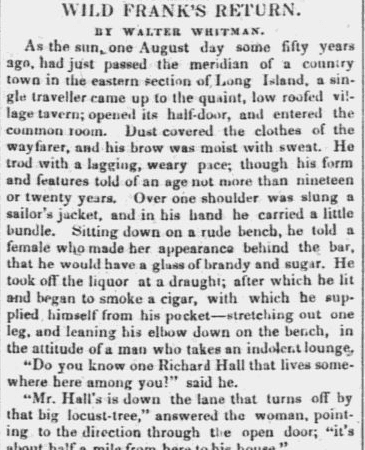

It’s often stated that Walter Whitman went by Walt Whitman to be distinguished from his father, Walter Whitman.

But not everything he wrote was published under the name Walt Whitman. For example, this 1841 newspaper published his story “Wild Frank’s Return” using the name “Walter Whitman.”

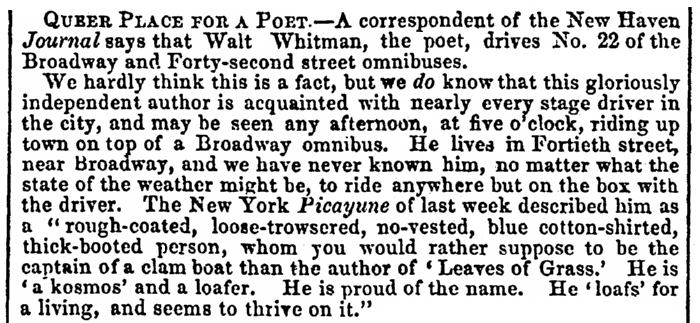

And then there’s the matter of whether or not Walt Whitman drove an omnibus (a horse-drawn streetcar).

It’s often written that Whitman was well acquainted with bus drivers, but modern authors miss a tidbit that was reported in this 1859 newspaper article. Whether or not this was a permanent position or just a diversion, Whitman was spotted driving the No. 22 omnibus of the Broadway and Forty-second street line in New York City, and it was reported that he often rode on top of omnibuses on the box with the driver.

Louisa May Alcott

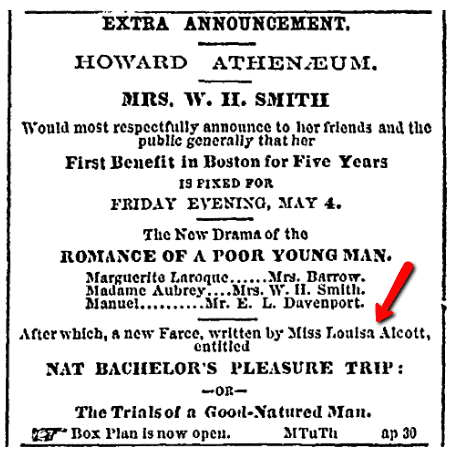

Historical writers almost always refer to the author of Little Women as Louisa May Alcott – but as we saw with Walter “Walt” Whitman, her name didn’t always appear the same way. In the newspaper advertisement below, she was identified as “Louisa Alcott.”

In 1860 a farce Alcott authored, called Nat Bachelor’s Pleasure Trip, was performed in Boston. Some historical researchers claim that upon seeing the evening program, she was appalled that her middle name was omitted and her last name misspelled.

Genealogy Tip: when an author claims to know a person’s thoughts, see if the subject ever stated the same thoughts in writing. In this case, do we really know what Louisa May Alcott thought at seeing herself identified in print as “Louisa Alcott”? And another tip: this example, as with the previous example of Walter/Walt Whitman, remind us not to assume an ancestor’s name always appeared the same way. Search on variations of your ancestor’s name to find as many relevant newspaper articles as possible.

Eli Whitney

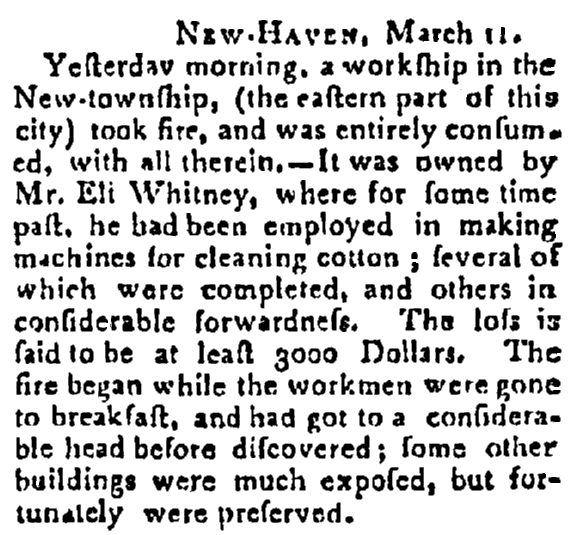

Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin in 1794, but most researchers have overlooked a setback that occurred the very next year. In 1795, several of his machines for cleaning cotton were consumed in a fire. Losses totaled at least $3,000, a tidy sum at that time.

You can read the report in this 1795 newspaper article.

Tips for Questioning Historical Reports (Author Oversights)

As you can see, reports aren’t always what they appear to be. Here are some tips for evaluating if a statement is the truth or simply a mistake caused by an author oversight.

- Reports of “first time” dates concerning your ancestry can often be substantiated or disproved in newspaper advertisements and articles.

- If a well-meaning historian tells you why your ancestor moved from one place to another, see if you can find the underlying reason in the papers. There may have been a law, epidemic, inheritance or another incentive that the author missed.

- Vary a person’s name according to their age in your genealogical reports. As we see today, people of the past often changed their personal identities throughout their lifetime. A child might go by one name, a young adult by another and an older individual by another.

- If a writer veers into fiction by claiming to have known a person’s thoughts, see if you can find a supporting reference, such as with the Louisa Alcott advertisement.

- Our ancestors often faced setbacks, such as the fire that consumed Eli Whitney’s workshop. When they happened, the news was usually printed.

- Take note of phrases and pseudonyms found in articles and use them in your genealogical queries. As seen with the Whitney report, the author referred to a cotton cleaning machine, rather than the cotton gin.

- To be historically accurate, read early newspapers to learn terms used by our ancestors.

Related Articles:

- Get Your Genealogy Facts Straight: Proof-Checking Tips for Records

- Family History Fact Finding: True Family Stories in Newspapers

- How to Research Historical Events for Genealogy with Newspapers

- Where Was George Washington? Revolutionary War Fact Checking

- Fact or Myth: Did Horace Greeley Really Say ‘Go West Young Man’?