Paul Revere, a patriot during the American Revolution best known for his midnight ride in April 1775 to warn the colonial militia that the British were coming, died on this day in 1818. He was 83 years old.

Revere was a businessman, soldier, silversmith, engraver, dentist, and industrialist who established foundries to work in iron, bronze and copper. He was one of the early Sons of Liberty, and a leader of the Boston Tea Party. Beginning in 1773, Revere was the trusted courier for the Committee of Public Safety in Boston, carrying essential messages to New York and Philadelphia at great personal risk to himself.

He made 18 of these daring and important rides, but it was his “midnight ride” of April 1775 that won him everlasting fame, as immortalized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1860 poem “Paul Revere’s Ride” that begins:

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

The bells tolled in Boston on the day Revere died.

Newspapers everywhere reported his death.

Here is a transcription of this article:

On Sunday departed this life, PAUL REVERE, Esq. in the 84th year of his age. During his protracted life, his activity in business and benevolence, the vigor of his mind, and strength of his constitution were unabated. He was one of the earliest and most indefatigable Patriots and Soldiers of the Revolution, and has filled with fidelity, ability and usefulness, many important situations in the military and civil service of his country, and at the head of valued and beneficent institutions. Seldom has the tomb closed upon a life so honorable and useful.

Eighty years after he died, in 1898, the following newspaper article recalled the patriotism of Paul Revere in an attempt to rouse Americans in support of the Spanish-American War. This article gave a dramatic account of his famous “midnight ride.”

Here is a transcription of this article:

PAUL REVERE’S RIDE.

An Echo of the Days of Freedom’s Struggle.

When Trouble Began between the Colonies and the Mother Country, He Became the Trusted Messenger of the Patriots and Traveled Thousands of Miles.

With the nation arming for what may be another memorable conflict, the days of that first call to duty, in April 1775, when was fired the shot “heard around the world,” come to the memory of Americans. Of the many stirring deeds done during the “times that tried men’s souls,” the midnight ride of Paul Revere was the most important and brilliant single exploit.

When trouble began between the colonies and the mother country, Paul Revere became the trusted messenger of the patriots and traveled thousands of miles on his faithful horse, carrying messages between various “Committees of Safety.” Hancock, Adams, Dr. Warren and other patriots, whose names are dear to every American, were his friends, and frequently employed him to carry messages of the greatest importance to the cause of liberty.

In a letter to Dr. Belknap, dated Boston, January 1, 1798, Paul Revere himself modestly tells the story of his patriotic services. He writes: “In the year 1773, I was employed by the selectmen of the town of Boston to carry the account of the Destruction of the Tea to New York; and afterward in 1774, to carry their dispatches to New York and Philadelphia for calling a Congress; and afterward to Congress several times. In the fall of 1774, and winter of 1775, I was one of upwards of thirty, chiefly mechanics, who formed ourselves into a committee for the purpose of watching the movements of the British soldiers, and gaining intelligence of the movements of the Tories. We held our meetings at the Green Dragon tavern. We were so careful that our meetings should be kept secret that every time we met each one swore upon the Bible that he would not discover any of our transactions but to Messrs. Hancock, Adams, Doctors Warren and Church and one or two more.”

This was before his famous midnight ride. On April 18, 1775, a movement among the British troops stationed at Boston was noticed. It was thought they intended to start for Concord and Lexington that night. If the British marched the people must be warned. It was also important to know whether the British were to go by water or by land. Paul Revere offered his services. It was agreed to show two lanterns in the Christ Church steeple, if the British went by water, and one, if by land, as a signal. Captain John Pulling, a friend of Revere, was to make the signals. These arrangements all completed, Paul Revere returned to his home to prepare for the memorable ride.

He took his boots and surtout [overcoat], and went to one of the wharves where he kept his boat, and was rowed across the Charles river by two of his friends. Here, with eyes fixed in the direction of the church tower, he awaited the signals. The dark waters of the Charles river flowed between him and Boston. It was getting late. One by one he saw the lights of the city go out. The silence of the night was all around him.

The signals! How his stout heart throbbed at the thought of what they meant to his country. Would they never appear? Suddenly, a few minutes before 11 o’clock, there was a glimmer of light in the tall church tower. Then, clear and bright, shining across the dark river, Paul Revere saw the signal lights. There were two. The British were going by water. No need to wait longer. He had a nation to arouse.

He sprang to the back of his horse, dug the rowels [spurs] into the animal’s sides and, like the wind, was away. “The Regulars are coming!” he shouted, as he dashed by the lonely farm houses. “The Regulars are coming! The Regulars are coming! Turn out! Turn out! The Regulars are coming!” No need to stop to explain. All knew what that terrible warning cry meant. There was no more sleep for the people that night.

It was near midnight when Paul Revere galloped into Lexington. He rode at once to the house of Rev. Mr. Clark, where Hancock was staying. The guard stationed around the building at first would not admit him, and cautioned him not to make any noise.

“Noise!” exclaimed Revere. “Noise! You will have noise enough before long. The Regulars are coming out!”

Hancock heard his voice and called out: “Come in, Revere! We are not afraid of you!” and in he went.

His famous ride was over. He had aroused the nation. He had ridden better than he knew. But the work of Paul Revere was not done; nor was this last perilous ride for the good of liberty. His services won for him the title of “The Messenger of the Revolution.” He was a gallant soldier, and served faithfully throughout the long war, winning the rank of lieutenant colonel.

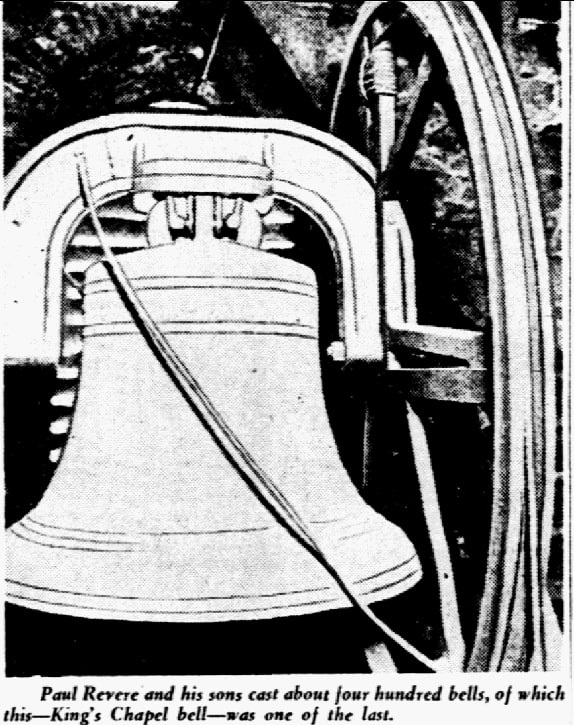

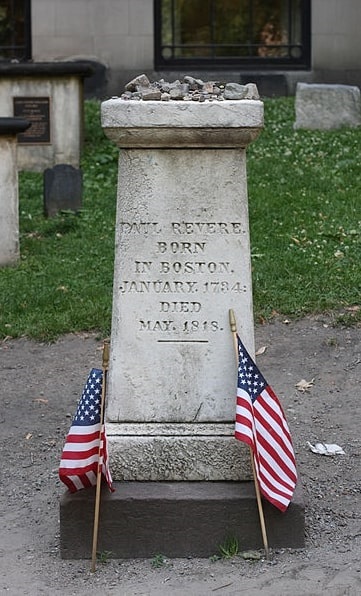

At the close of the war, in 1783, he opened a foundry at the north end of Boston, where he cast church bells, brass cannons and iron ware. He also continued his work as an engraver. In 1801, he and his son established a large foundry at Canton, where they did an extensive business, rolling copper plates and making copper bolts and spikes, and casting bells and cannons. The bells and spikes used in the famous [ship] “Constitution” were made by Paul Revere. It is pleasant to learn that Paul Revere was successful in business, reared a large family and died esteemed by all who knew him. He was eighty-[three] years old when death came on May 10, 1818; and was buried in Granary Burying Grounds, Boston, where a small monument marks his grave.

More than a century after he died, Esther Forbes wrote a biography of Paul Revere – and in reviewing that book, Margaret Leachman wrote the following essay.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Paul Revere Lived in American Epoch of Heroic Temper

“Paul Revere and the World He Lived In.” By Esther Forbes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. $3.75.

Esther Forbes is habitually a novelist rather than a biographer, but a biographer she is in her latest book, Paul Revere and the World He Lived In. In it she gives the reading pubic of America a 464-page close-up of the twenty years preceding the American Revolution and corrects many fictionalized tales about great characters and events of this thrilling period – notably the causes for the Revolution, and the midnight ride of Paul Revere. She is also minutely concerned with the customs and everyday life of provincial Boston.

Paul Revere himself was a commonplace, middle-class man, and no biographer could make his life interesting without coloring it – a thing Miss Forbes refuses to do. Thus, the excitement in her book may be attributed to the part in the Revolution played by Boston and Bostonians. Of the latter, she presents quite a few full-length portraits, including Governor Thomas Hutchinson, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Joseph Warren and James Otis.

The intimate views of these great men vouch for the author’s detailed research, and her style in presenting them smacks ever so lightly of Time – “… the unknown, pock-marked George Washington”; “… the famous amphibious General Glover.” The whole of Paul Revere is clear, absorbing reading, full of history and details, but not textbookish in the least.

“Bold Revere.”

His contemporaries called Paul Revere “Bold Revere” – to this Miss Forbes adds “steady, vigorous, sensible, persevering – a nice balance between good sense and boldness characterized his whole life.” He is famous to the ordinary person for his ride and his silversmithing, but he was also a soldier in the French and Indian War, and engraver, a dentist, a bell caster, a politician, and the father of sixteen children. He was accepted into the circle of Harvard-educated revolutionaries – James Otis, Sam Adams, John Adams and John Hancock, to mention a few – not as an equal but as “my worthy friend,” and “a man of his rank and opportunities in life.”

At the time of his ride he was a middle-aged man merely performing his duty; not a propagandized youth fired with the inspiration of freedom. Robert Newman was the one who hung the lanterns in Christ’s Church while Paul Revere rode on to Charlestown and Lexington. He remained an active though not a very celebrated soldier throughout the Revolution, attaining the rank of lieutenant colonel. After the war he was a vigorous Republican, opposing everything concerning Jeffersonian Democrats.

He continued his work in silver and is said to be the greatest silversmith in his day. As he grew older he concentrated on bell casting and rolling copper. His finest bell was hung in King’s Chapel and was the death bell for Boston. On May 10, 1818, this bell tolled out three, then eight, then three strokes, for the death of an eighty-three-year-old American – the man who had cast it two years earlier.

Note: Just as an online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, helped tell the stories of Paul Revere’s life, they can tell you stories about your ancestors that can’t be found anywhere else. Come look today and see what you can discover!