By the spring of 1917, World War I had been raging for nearly three years. In the trenches of Europe and on battlegrounds in Africa and the Middle East, nations were tearing themselves apart and sacrificing millions of their young men. Anxiously pacing on the sidelines of this great conflict and keeping a wary eye on the growing carnage was America, doggedly pursuing a strained policy of neutrality.

However, Germany’s declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare in January 1917, and the publication of the “Zimmerman telegram” revealing a German plot to have Mexico and Japan declare war on the U.S., put an end to American forbearance. On 2 April 1917, President Woodrow Wilson delivered a powerful speech asking Congress to declare that a state of war existed with Germany, a request Congress – and the general public – embraced. American neutrality was at an end.

Congress declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. American involvement helped turn the tide in favor of the Allies, and the war came to an end when the Armistice was declared at 11:00 on 11 November 1918.

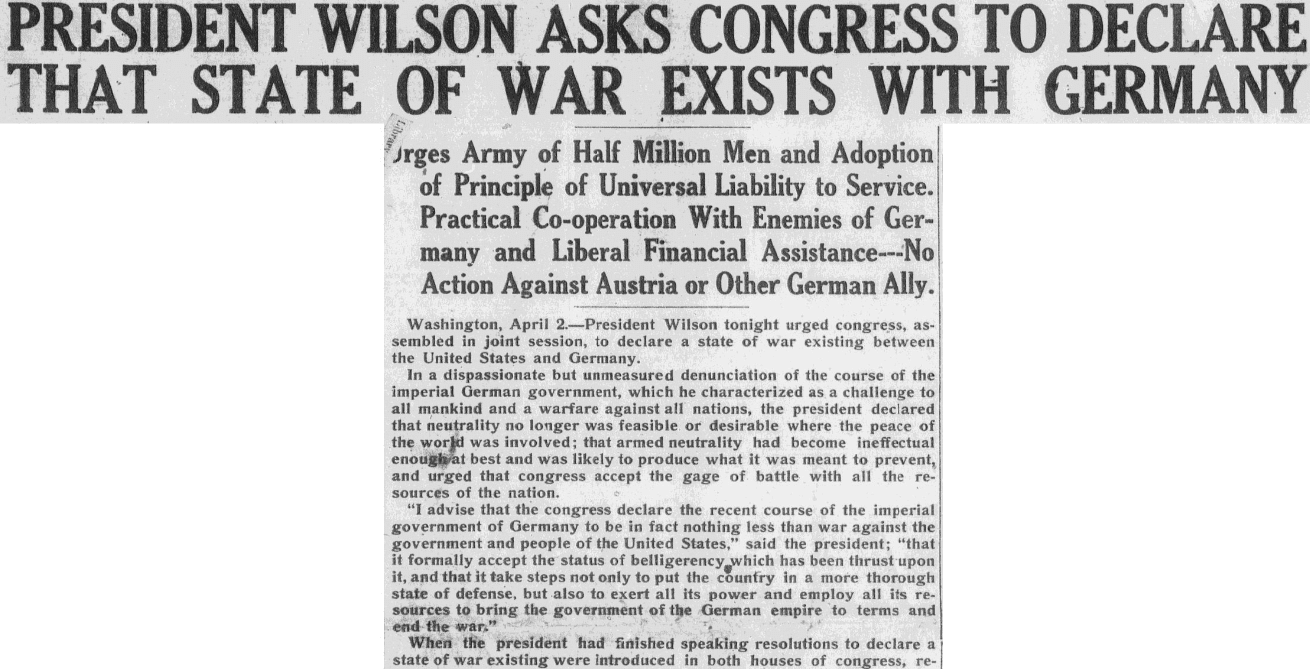

PRESIDENT WILSON ASKS CONGRESS TO DECLARE THAT STATE OF WAR EXISTS WITH GERMANY

Urges Army of Half Million Men and Adoption of Principle of Universal Liability to Service. Practical Cooperation with Enemies of Germany and Liberal Financial Assistance. No Action against Austria or Other German Ally.

Washington, April 2. – President Wilson tonight urged Congress, assembled in joint session, to declare a state of war existing between the United States and Germany.

In a dispassionate but unmeasured denunciation of the course of the imperial German government, which he characterized as a challenge to all mankind and a warfare against all nations, the president declared that neutrality no longer was feasible or desirable where the peace of the world was involved; that armed neutrality had become ineffectual enough at best and was likely to produce what it was meant to prevent, and urged that Congress accept the gage of battle with all the resources of the nation.

“I advise that the Congress declare the recent course of the imperial government of Germany to be in fact nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States,” said the president; “that it formally accept the status of belligerency which has been thrust upon it, and that it take steps not only to put the country in a more thorough state of defense, but also to exert all its power and employ all its resources to bring the government of the German empire to terms and end the war.”

When the president had finished speaking, resolutions to declare a state of war existing were introduced in both houses of Congress, referred to appropriate committees and will be debated tomorrow. There is no doubt of their passage.

ASKS VINDICATION OF PEACE AND JUSTICE

The objects of the United States in entering the war, the president said, are to vindicate the peace and justice against “selfish and autocratic power.”

“Without selfish ends, for conquest or dominion, seeking no indemnities or material compensations for the sufferings it shall cause, the United States must enter the war,” he said, “to make the world safe for democracy, as only one of the champions of the rights of mankind, and would be satisfied when those were as secure as the faith and freedom of nations could make them.”

The president’s address was sent in full to Germany by a German official news agency for publication in that country. The text also went to England and a summary of its contents was sent around the world to other nations.

Foe to Liberty.

To carry on effective warfare against the German government, which he characterized as a “natural foe to liberty,” the president recommended:

Utmost practical cooperation in counsel and action with the governments already at war with Germany.

Extension of liberal financial credits to those governments so that the resources of America may be added so far as possible to theirs.

Organization and mobilization of all the material resources of the country.

An army of at least 500,000, based on the universal liability to service, and the authorization of additional increments of 500,000 each as they are needed or can be handled in training.

Full equipment for the navy, particularly for means of dealing with submarine warfare.

Raising necessary money for the United States government so far as possible without borrowing and on the basis of equitable taxation.

All preparations should be made in such a way as not to check the flow of war supplies to the nations already in the field against Germany.

Measures to accomplish all these ends, the president told Congress, would be presented with the best thought of the executive departments which will be charged with the conduct of the war, and he besought consideration for them in that light.

Greatest Enthusiasm.

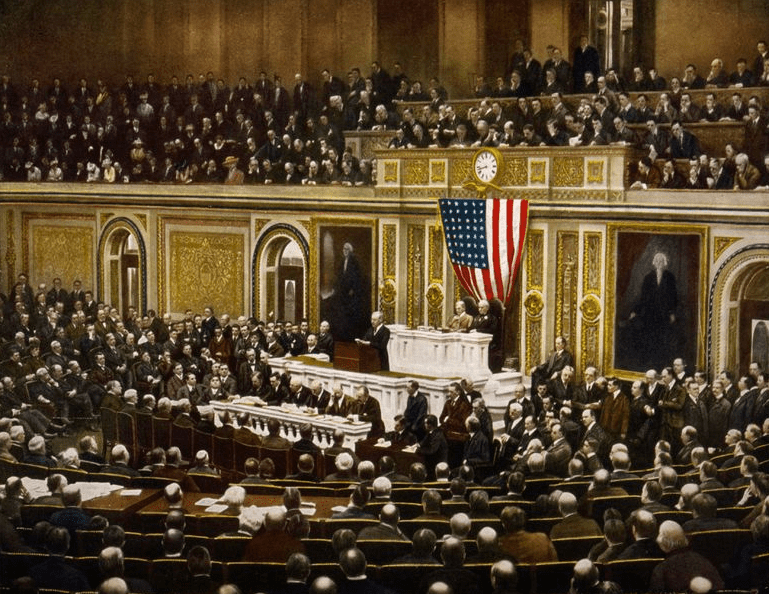

President Wilson’s appearance before Congress was marked by a scene of the greatest enthusiasm shown since he began delivering his addresses in person. Crowds on the outside of the Capitol cheered him frantically as he entered and as he left. Congress roared cheer after cheer in an outburst of patriotic enthusiasm.

From the galleries the only members who appeared not to be joining in the demonstration were some senators of the group which the president branded as “willful men,” who by preventing a vote on the armed neutrality bill had made the “great government of the United States contemptible.”

Chief Justice White was among those who cheered loudly and there was no division of spirit between Republicans and Democrats.

Referring only briefly to the long trouble with Germany in his effort to bring them back to the bounds of humanity and nations, the president launched into denunciation of the course of Germany, which he declared had made the United States a belligerent.

“The wrongs against which we now arm ourselves,” he said, “are no common wrongs. They cut to the very roots of human life.”

Friendship for Germans.

Disclaiming any quarrel with the German people and anything but a feeling of friendship and sympathy for them, the president declared their government had not acted upon their impulses in entering the war, nor with their previous approval.

“It was a war,” he said, “determined upon as wars used to be determined upon in the old unhappy days when peoples were not considered by their rulers and wars were provoked and waged in the interest of dynasties or of little groups of ambitious men who were accustomed to use their fellow men as pawns and tools.”

In scathing terms the president referred to the German plots against the United States: “One of the things that has served to convince us that the Prussian autocracy was not and never could be our friend is that from the very outset of the present war it has filled our unsuspecting communities and even our offices of government with spies and set criminal intrigues everywhere afoot against our national unity of council, our peace within and without, and our commerce.”

It was evident, the president added, “that spies were here even before the war began.” That the German government tried to stir up enemies at the very doors of the United States was eloquently proved, he said, by the revelation of the plot to embroil Japan and Mexico in war with the United States.

Never Can Be a Friend.

“We are accepting this challenge of hostile purposes,” said the president, “because we know that in such a government following such methods, we can never have a friend, and that, in the pursuance of its organized power, always lying in wait to accomplish we know not what purpose, there can be no assured security for the democratic governments of the world.”

The whole nation’s resources, if necessary, the president declared, would be spent against this “natural foe to liberty” and to “check its pretensions and power.”

Toward Germany’s allies, the president said, the United States was taking no action at this time because they were not engaged in warfare against Americans on the seas.

The Untied States, he said, was moving only against an “irresponsible government which has thrown aside consideration of humanity and of right and was running amuck.”

Confident of Loyalty.

The president explained his confidence in the loyalty of naturalized citizens, and declared that if disloyalty did lift its head, it would be only from “a lawless and malignant few” and would be sternly suppressed.

While the president was speaking word of the torpedoing without warning of the American steamer Aztec, the first American armed ship to be attacked in the barred zone, was passed from mouth to mouth, but the president did not know of it until he had finished.

The president returned to the Capitol about 8 o’clock.

As his big motor swung around before the east front of the building, two troops of the Second regiment of cavalry on guard, sabers glittering under the arc lights, swept the plaza clear, while the hundreds of people cheered. He was taken immediately to the speaker’s room, and then into the House chamber, where the senators were just filing in. Six members of the Supreme Court, who had taken seats in front of the speaker’s stand, stood and faced about.

Wildly Cheered.

The president entered amid wild cheers. It was noticed that Senators La Follette, Stone and Cummins, who helped defeat the armed neutrality bill in the last session, did not join in the applause.

Senator La Follette stood with arms crossed and head sunk over his chest. Senator Lane, another of the group, applauded mildly, and Senator Kenyon more vigorously.

The president spoke slowly at first and then as fast as usual. His voice was clear and grew stronger as he proceeded.

It was a very serious and quiet audience. Not until the president declared, “we will not choose the path of submission,” did his auditors applaud.

Scarcely had the sounds of this demonstration died away when the president declared that the Congress should declare that a state of war existed and a second demonstration began.

Greatest Outburst.

By far the greatest outburst, however, came when the president declared for an army of 500,000 men selected on a universal service basis. As the president faced every person on the floor and in the galleries, they all shouted.

The president went immediately to Speaker Clark’s room, and after a brief talk with the members of the committee accompanying him, returned to the White House with members of his family and Col. E. M. House, remaining up until midnight.

When Congress works tomorrow on the war resolution the Cabinet will hold a war session, to which Major General Scott, chief of staff of the Army, and Admiral Benson, chief of operations of the Navy, may be invited. Meanwhile many days of hurried preparation for the eventuality which now confronts the nation have borne the fruit and remain only to be carried further.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in World War I? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles: