One of the reasons the American colonies were so important to the British crown was the abundance of natural resources that the King could no longer get in Britain. One of these natural resources was timber, meaning the pines growing in New England were very valuable.

While researching my fifth-great-grandfather Silas Hanson (1727-1775), I learned something interesting: Silas was involved in the timber industry and helped supply masts for the King’s ships.

Silas was born in Dover, Strafford County, New Hampshire, in 1727. I was searching the New Hampshire newspapers in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives for Silas’ name and the keyword “Dover” when I came upon the following newspaper article about the New Hampshire pine industry.

According to this article:

“The forests in some parts of our county, at its first settlement, abounded in Mast Pines, of the finest quality, and afforded profitable employment to a great number of the hardy yeomanry for a long period previous to the separation of America from Great Britain.”

Further down in the article, my great-grandfather Silas Hanson is named as having been on the crew that hauled these felled pines out of the forests and to the edge of the water, where they would be shipped.

An internet search for “masting in colonial New Hampshire” led me to an article by King’s Mark Resource Conservation & Development Project, which describes how important these pines were to the Crown:

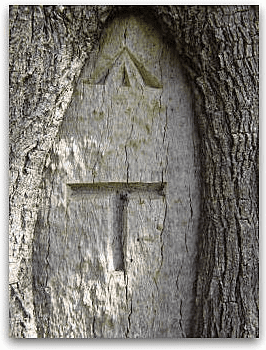

“Great Britain had depleted its forests by the 17th century and looked to the tall, straight white pines [of] the colonies to supply its appetite for timber for wooden ships, especially the old-growth pines for masts… To maintain its world dominance of the seas, Great Britain needed the strongest and fastest ships. Eastern White Pine made these ships the greyhounds of their day and a force to reckon with in any battle. As a result, King George I of England wanted to ensure that the very best of the trees were kept for official use… To ensure that the best of the mast trees remained available for the Royal Navy and British shipbuilders, England declared the largest white pines to be the property of the King, marked, protected, and harvested for the government’s use.”

Eventually, the timbermen in Goffstown and Weare, New Hampshire (over an hour away from Dover) got sick of the King controlling all of the region’s timber, and began fighting back against a law that prohibited colonial use of pines that were over one foot in diameter – eventually culminating in the Pine Tree Riot of 1772. A Wikipedia page on the Pine Tree Riot describes the incident:

“John Sherman, Deputy Surveyor of New Hampshire, ordered a search of sawmills in 1771-1772 for white pine marked for the Crown. His men found that six mills in Goffstown and Weare possessed large white pines and marked them with the broad arrow to indicate that they were Crown property… The mill owners from Goffstown paid their fines at once and had their logs returned to them.

“Those from Weare refused to pay… On April 13, 1772, Benjamin Whiting, Sheriff of Hillsborough County, and his Deputy John Quigly were sent to South Weare with a warrant to arrest the leader of the Weare mill owners, Ebenezer Mudgett. Mudgett was subsequently released with the understanding that he would provide bail in the morning… At dawn the next day Mudgett led between 20 and 30-40 men to Whiting’s room and assaulted the offending officials. Their faces blackened with soot, the rioters gave the sheriff one lash with a tree switch for every tree being contested… The Pine Tree Riot was a test of the British royal authority. This is partially evident by the light fines exacted against the rioters. Some believe this to be an inspiring act for the Boston Tea Party.”

Fascinating – I had no idea my distant great-grandfather was involved in the timber industry, or that it was so controversial in the years leading up to the Revolution.

Genealogy Tip: Find out how your ancestors made American history by searching for them in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives.

I wonder if the mark on that tree in the photo is original to the Colonial era, or if it was made later, a kind of reproduction?