Introduction: In this article, Melissa Davenport Berry continues her story about many battles over the estate of railroad magnate Mark Hopkins, focusing on the 1920s. Melissa is a genealogist who has a website, americana-archives.com, and a Facebook group, New England Family Genealogy and History.

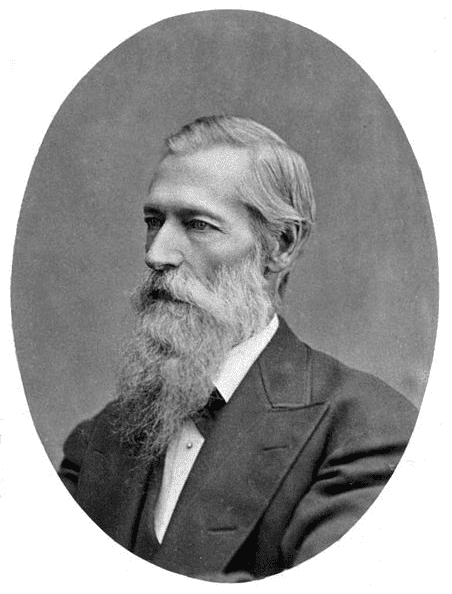

Though born poor, Edward Francis Searles became an enormously wealthy man when he married the widow Mary Hopkins in 1887 (she had inherited the vast fortune of her husband, railroad magnate Mark Hopkins). Edward’s courtship of Mary had caused a scandal – she was almost 70 when she married her suitor, a man 23 years her junior.

More scandal ensued when Edward insisted his male “friend,” Arthur T. Walker, move in with him and Mary. When Edward died in 1920, he left the Mark Hopkins fortune to his dear friend Arthur. That’s when the mad scramble for Mark Hopkins’ riches really began.

Rumors were everywhere. It was reported that a bank in San Francisco, California, had a vault holding envelopes with securities of $350,000,000 in a trust for Mark Hopkins’ heirs whenever they should be located.

The press sparked a treasure hunt and the lawyers took advantage of the publicity. From 1924 to 1929 over a thousand claims were filed by supposed heirs and co-heirs, and even the most remote relations. They came – or their lawyers came – with forged wills, fake Bibles, and bogus family trees to show a genealogical connection to Mark Hopkins.

Lawyers Reap the Riches

The lawyers gained great riches and pooled the Hopkins hopefuls together in class actions suits. They charged $50 to $100 for each claimant to join in the legal claim.

Some claimants, like Estella Latta of Durham, North Carolina, sold Hopkins stocks to finance the huge litigation fees.

One judge, fed up with the mess, ordered an investigation of the cases which reached “racket proportions.” The judge accused the predatory lawyers of keeping the treasure hunt alive.

The contest for the Mark Hopkins estate took on a life of its own. In fact, it would take years of research to sift through entirely, but GenealogyBank and library scrapbooks from the archives provide many colorful, entertaining stories. Timothy Hopkins, the adopted son of Mary Hopkins whom she cut out of her will before leaving it all to Edward, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch “it is the result of the most amazing pieces of propaganda ever spread in America.”

The New Gold Rush

In a 21 July 1929 article entitled “A New Gold Rush Is On,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported:

“These treasure seekers… They are burdened with affidavits and depositions, instead of picks and shovels, but the lure is the same as it was in [the Gold Rush of] ’49.”

There was an added ingredient that promoted the new gold rush, which Salvador A. Ramirez points out in his book The Inside Man: The Life and Times of Mark Hopkins of New York, Michigan, and California. Ramirez asserts that when Timothy Hopkins was working to construct his genealogy (to make his own claim), he placed ads in North Carolina newspapers seeking information regarding one of Rev. Samuel Hopkins’ descendants who had migrated to that state:

“Thus, began a virtual cottage industry to obtain legal standing in order to challenge the original settlement decree of the Mark Hopkins estate.” (p. 1073)

(Timothy Hopkins Papers at Stanford University Archives has this research.)

Here are some of the claims I uncovered.

The “Lost Will” Discovered in a Cabin

In 1926 a purported lost will surfaced. It was found in an old cabin in Hillsboro, North Carolina, and a David S. Moore was said to have all the details and evidence – but David went missing.

According to the newspapers, David’s mother, Hannah Jordon Moore, was a former sweetheart of Mark Hopkins when he was living in North Carolina as a young man. Supposedly, Mark wrote a will on Christmas Day in 1874 – four years before he died – in the famous Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco and mailed it to Hannah. This was the will David claimed to have found in the cabin.

Hannah said her son David was really the son of Mark Hopkins and the rightful heir to his huge fortune.

After being questioned by the attorneys, David Moore disappeared. According to the locals, he and his lawyer had a “word battle.” David’s lawyer was in a stew because his deposition was crucial for the case.

The Moore family said Mark Hopkins came back to North Carolina to visit in 1875, and traveled incognito on a horse dressed in shabby clothes because he feared he would be killed for his money. But his clothing was lined with bank notes and his pockets with gold coins. He was very liberal with his relatives and handed them all $20 gold pieces.

The Colorado Claim

Meanwhile in Denver, Colorado, a steel worker, Frank Hopkins, announced to the Denver Post that he was in possession of family papers that connected him to Mark Hopkins via his father Thomas James Hopkins, who supposedly was a nephew of the magnate.

According to Frank, a letter was written to his father from the Hopkins estate administrator requesting him to travel to California to claim part of his share of the estate. However, the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 and resulting fire made it impossible for his father to locate the administrator because of all the confusion, and he just plain gave up and returned to Grand Junction.

Frank told the reporter that he was heading out to California with his wife Josephine and three sons Bernard, Frank, and Robert to start ligation after the Christmas holiday. He also claimed there were others who were entitled to the gravy train, including his father’s sister, Mrs. Margaret Hawkins, her son Mark Hopkins Hawkins, and three daughters.

More North Carolina Claims

In 1927 the Charlotte Observer correspondent Margaret Brinkley visited claimants in Charlotte, North Carolina. Brinkley noted that “When we get the money” was the household phrase in many homes. They believed they were the most eligible heirs to win the Hopkins’ millions and “revealed visions of becoming millionaires via the Mark Hopkins fortune. They were represented by attorney Samuel Jones and they claimed to be descended from John (Jackie) Hopkins, alleged brother of Mark Hopkins.”

Mrs. Julia A. Stegner told Brinkley that she was not prepared to play the role of the “Merry Widow,” but the possession of a little money would do her “a sight of good.” B. L. Howell told Brinkley he planned to build a mansion of James Duke variety at Myers Park. The younger claimants like Pauline Sossoman told Brinkley, “When I get the money, I won’t have to bring in the wood anymore.”

They had a witness, Albert Alexander Harvell, who claimed to know the Hopkins boys who went out during the California Gold Rush in 1849. Then he gave a list of family members that were associated with the Hopkins line.

More stories about the Hopkins fortune saga are coming…

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Genealogy:

- I found some information on David S. Moore’s parents. His mother was Elizabeth “Bettie” Hannah Jordon, daughter of Thomas R. Jordan and Sarah “Sallie” Wilkerson. She married John Moore on 15 August 1865. She died 19 June 1926. Her death certificate was signed by David. John Moore was listed in the 1850 census as eight years old, living with his parents Jesse and Mary Moore. John served in the Civil War and I found a death certificate in 1865. David married Annie L. Clayton on 1 August 1896. He died of a massive heart attack on 14 May 1938.

Related Articles: