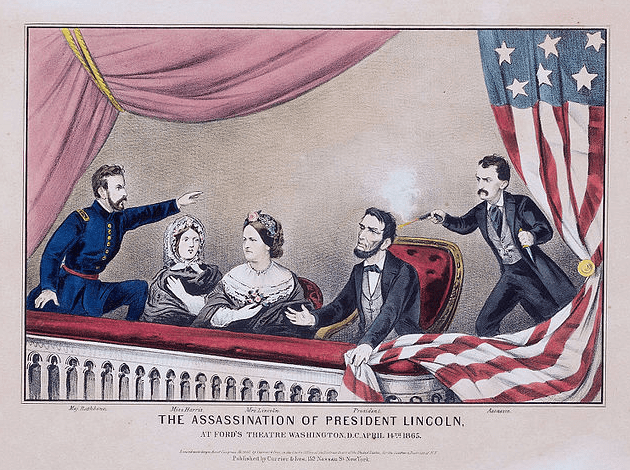

Just five days after celebrating the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, euphoria in the North suddenly plunged into grief and despair when President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on 14 April 1865.

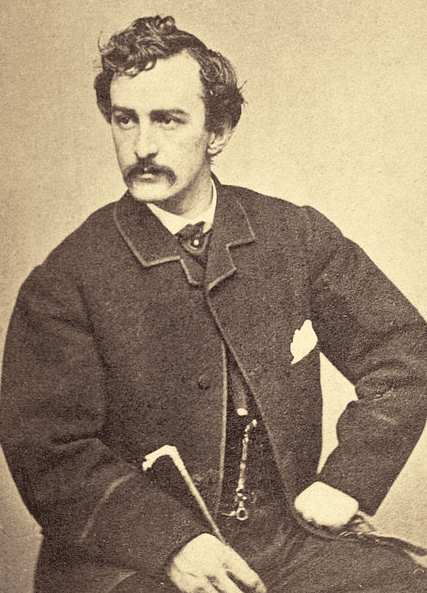

The murderer was John Wilkes Booth, a 26-year-old actor and fervent Southern sympathizer, who shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., while the president was enjoying a performance of Our American Cousin.

A determined 12-day manhunt ensued, which Booth and fellow-conspirator David Herold managed to avoid by riding into Maryland, crossing the Potomac River, and hiding out in rural northern Virginia. Before dawn on 26 April 1865, the law and federal forces caught up to them. The fugitives were hiding in a barn on Richard Garrett’s farm, which the detectives and cavalrymen surrounded.

Herold surrendered, but Booth vowed to fight to the last. With a mortal gunshot wound in his neck and the barn on fire, Booth finally staggered out of the barn and was captured. He was in great pain, and died two agonizing hours later on the porch of the Garrett farmhouse.

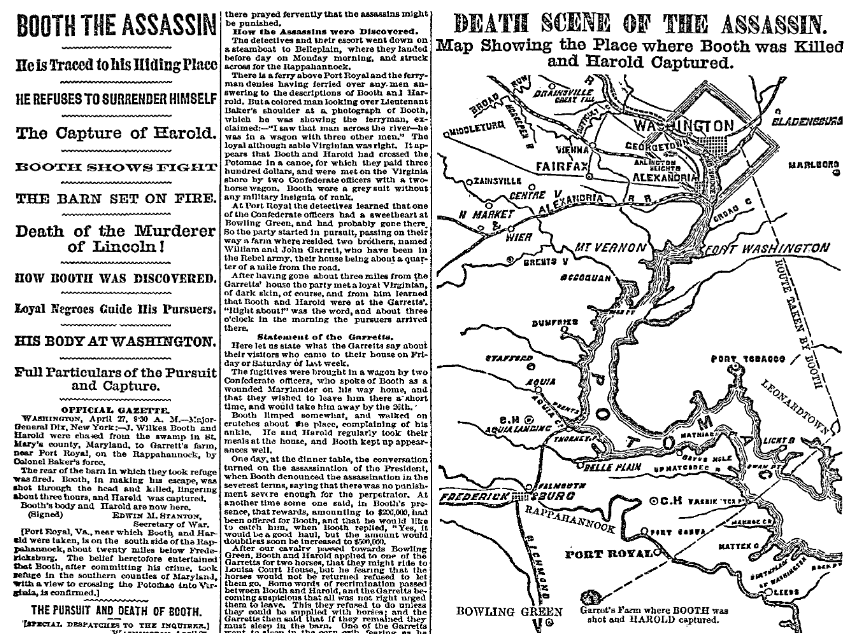

The news of the shooting of John Wilkes Booth made the front pages of newspapers all across the country.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Booth the Assassin

He Is Traced to His Hiding Place

He Refuses to Surrender Himself

The Capture of Harold [Herold – ed.]

Booth Shows Fight

The Barn Set on Fire

Death of the Murderer of Lincoln!

How Booth Was Discovered

Loyal Negroes Guide His Pursuers

His Body at Washington

Full Particulars of the Pursuit and Capture

Official Gazette.

WASHINGTON, April 27, 9:30 A.M.

Major General Dix, New York:

J. Wilkes Booth and Harold were chased from the swamp in St. Mary’s county, Maryland, to Garrett’s farm, near Port Royal, on the Rappahannock, by Colonel Baker’s force.

The rear of the barn in which they took refuge was fired. Booth, in making his escape, was shot through the head and killed, lingering about three hours, and Harold was captured. Booth’s body and Harold are now here.

(Signed) Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War.

(Port Royal, Va., near which Booth and Harold were taken, is on the south side of the Rappahannock, about twenty miles below Fredericksburg. The belief heretofore entertained that Booth, after committing his crime, took refuge in the southern counties of Maryland, with a view to crossing the Potomac into Virginia, is confirmed.)

The Pursuit and Death of Booth.

(Special dispatches to the Inquirer.)

WASHINGTON, April 27.

Booth, after assassinating President Lincoln and making a tragic exit from the stage of the theatre, mounted his horse and rode off, accompanied by an accomplice, named Harold, a young Marylander [23-year-old David Herold – ed.]. To avoid suspicion, they separated, meeting at a place called Marlboro.

Booth, in jumping from the box, had fractured one of the small bones of his left leg, just above the ankle, and the limb had swollen during the ride, causing much pain. Harold took him to the house of a Dr. Mudge [Samuel A. Mudd – ed.], where the boot was cut off and the limb bandaged.

The two fugitives remained some days in Maryland, and Harold states that he saw the cavalry and detectives very near their place of concealment several times.

They were harbored by sympathizers with the Rebel cause, and the only persons who have given any information about them are those loyal Southerners who are easily distinguished by their dark skins.

Col. Baker on the Track of the Assassins.

Meanwhile, Colonel L. C. Baker, Provost Marshal of the War Department, had taken no part in the search made in Maryland for Booth by a large military force, aided by Colonel Olcott and the New York detectives, as he was waiting for some definite information of his whereabouts.

On Monday afternoon he received intelligence that Booth and Harold had probably crossed the Potomac at Swan’s Point. Those engaged in searching for them did not know that they had crossed. Having consulted maps of Virginia, which he obtained from the office of the Coast Survey, Colonel Baker made up his mind that Booth and Harold must have gone to the vicinity of Port Royal, a quiet village below Fredericksburg, on the Rappahannock.

He accordingly wrote to General Hancock, requesting him to detail a commissioned officer and twenty-five cavalrymen to report to anyone he might designate. He then gave instructions to two of his detective force, Lieutenant Luther B. Baker and E. J. Conger, formerly Lieutenant-Colonel of the cavalry regiment which Colonel Baker commanded.

The escort, which subsequently reported and started off under the orders of Detectives Baker and Conger, belonged to the Sixteenth New York Cavalry, which has for some months been looking after Moseby’s guerrillas over in Virginia.

The Commander of the Escort.

Lieutenant Edward P. Dougherty [Doherty – ed.], who commanded the escort, was at one time a resident in Boston. When the Rebellion broke out he came here as a private in the New York Seventy-first, in which regiment he fought at the first Bull Run. He afterwards enlisted in the Berdan Sharpshooters, and was then transferred into the Sixteenth New York Cavalry, where he has so distinguished himself as to secure promotion.

He was especially commended last fall when, on making a reconnaissance near Culpeper Court House with a small force, he encountered Kershaw’s Rebel cavalry division, but gallantly cut his way out.

Booth’s Executioner.

Sergeant Boston Corbett, who shot Booth, is a religions enthusiast, who has made the character of Cromwell his study. He was born in England, is about thirty-three years old, and is by trade a hat finisher.

About seven years since, while in Boston, he experienced religion, and when baptized, assumed the name of the city where he became converted, and since then he has always prayed for Divine instruction before taking any step in life, and he says that he has always been prompted what to do.

He was at one time a prisoner at Andersonville, Georgia, and was one of a party of sixteen who escaped. They were hunted down with bloodhounds, and only himself and one of his companions were brought back alive.

On the Sunday after President Lincoln was assassinated Sergeant Corbett obtained leave to attend services at McKentree Chapel here, and there prayed fervently that the assassins might be punished.

How the Assassins Were Discovered.

The detectives and their escort went down on a steamboat to Belle Plain, where they landed before day on Monday morning, and struck across for the Rappahannock.

There is a ferry above Port Royal and the ferryman denies having ferried over any men answering to the descriptions of Booth and Harold. But a colored man looking over Lieutenant Baker’s shoulder at a photograph of Booth, which he was showing the ferryman, exclaimed: “I saw that man across the river – he was in a wagon with three other men.” The loyal although sable Virginian was right. It appears that Booth and Harold had crossed the Potomac in a canoe, for which they paid three hundred dollars, and were met on the Virginia shore by two Confederate officers with a two-horse wagon. Booth wore a gray suit without any military insignia of rank.

At Port Royal the detectives learned that one of the Confederate officers had a sweetheart at Bowling Green, and had probably gone there. So the party started in pursuit, passing on their way a farm where resided two brothers named William and John Garrett [the farm belonged to their father, Richard Garrett – ed.], who have been in the Rebel army, their house being about a quarter of a mile from the road.

After having gone about three miles from the Garretts’ house the party met a loyal Virginian, of dark skin, of course, and from him learned that Booth and Harold were at the Garretts’. “Right about!” was the word, and about three o’clock in the morning the pursuers arrived there.

Statement of the Garretts.

Here let us state what the Garretts say about their visitors who came to their house on Friday or Saturday of last week.

The fugitives were brought in a wagon by two Confederate officers, who spoke of Booth as a wounded Marylander on his way home, and that they wished to leave him there a short time, and would take him away by the 26th.

Booth limped somewhat, and walked on crutches about the place, complaining of his ankle. He and Harold regularly took their meals at the house, and Booth kept up appearances well.

One day, at the dinner table, the conversation turned on the assassination of the President, when Booth denounced the assassination in the severest terms, saying that there was no punishment severe enough for the perpetrator. At another time someone said, in Booth’s presence, that rewards, amounting to $200,000, had been offered for Booth, and that he would like to catch him, when Booth replied, “Yes, it would be a good haul, but the amount would doubtless soon be increased to $500,000.”

After our cavalry passed towards Bowling Green, Booth and Harold applied to one of the Garretts for two horses, that they might ride to Louisa Court House, but he fearing that the horses would not be returned refused to let them go. Some words of recrimination passed between Booth and Harold, and the Garretts becoming suspicious that all was not right urged them to leave. This they refused to do unless they could be supplied with horses; and the Garretts then said that if they remained they must sleep in the barn. One of the Garretts went to sleep in the corncrib, fearing, as he says, that the strangers would steal their horses.

Preparations for the Capture.

On returning to the Garretts’ house, Lieutenant Baker halted his force and going in obtained a reluctant confession from the brother there where the criminals were. Going out again, Lieutenant Baker aroused his escort, who had nearly all gone to sleep, and took them to the barn, around which he stationed them. He then advanced to the door and knocking with the butt of his revolver said, “Booth, we want you.” “Here I am,” replied the assassin, “who are you, Confederate or Yankee?” Lieutenant Baker informed him who he was and summoned him to surrender, but met with a defiant refusal.

Quite a parley ensued, Harold at one time expressing a desire to surrender, which Booth rebuked, denouncing him as a coward. Booth could see the party outside through the cracks of the barn, but they could not see him. He swore that he would never be taken alive, and declared that he could kill at least five men and then kill himself, should they attempt to break into the barn.

The Barn Fired.

At last, Lieutenant Baker, fearing that the guerrillas and the paroled Rebel soldiers, with whom the country swarmed, would come to the rescue, posted the cavalrymen around the barn and going to one end of it, which was filled with hay, pulled some through a crack and lighted it. The flames ran up the crack to the top of the haymow, over which they spread. The inside of the barn was now lighted up.

When Booth first saw the fire he clambered up on the mow, and vainly attempted to extinguish it. He then returned to his position on the floor between the two doors, with his back against the haymow, a revolver in each hand, and a Spencer carbine between his legs.

Harold Surrenders.

Meanwhile, the soldiers had approached the barn, and Harold, dropping his pistol, gave himself up, receiving Booth’s malediction as he left the burning barn.

Death of Booth.

Just afterwards the roof over the haymow began to crack as if it was falling in, and Booth made a movement. Some of those who were watching him say that he was about to kill himself, while others declare that he was intending to break out and escape. Be this as it may, Sergeant Corbett had a sight at him through a wide crack with his cavalry six-shooter, and pulled [the] trigger. The ball entered about where the President was shot, but passed entirely through Booth’s head. The murder has been avenged. “It’s all up now,” shrieked Booth, “I’m gone,” and he staggered towards the door of the barn. Lieutenant Baker received him, and taking him from the blazing barn, laid him on the ground, then sat down and took his head in his lap.

Booth did not deny his crime, and showed no signs of repentance or of humanity, except to ask Lieutenant Dougherty to give a message to his mother. His death was not easy, but at three minutes after seven his spirit passed away into the presence of an avenging God.

Return of the Escort.

Nothing remained for the party to do but to regain their steamboat at Belle Plain.

How Harold Was Taught to Walk.

They had to bring Booth’s body in a cart, and at first Harold had to walk, to which he, as a Maryland gentleman, objected; but after a rope was placed around his neck with a slip noose, and the other end of it was fastened to a cavalryman’s saddle he started off, taking good care that the rope should not tighten.

The Remains of Booth.

From Belle Plain Lieutenant-Colonel Conger rode overland to Alexandria, and reported to Colonel Baker yesterday afternoon, at half-past five.

When he left there were some hopes that Booth’s wound was not mortal.

Colonel Baker went to Alexandria to meet the steamer, and since then the body of Booth, by direction of the Secretary of War, has remained in his custody.

Surgeon-General Barnes, with an assistant, made an autopsy on the remains this afternoon. Their final disposition is unknown to the public as yet.

Such are the leading events of the escape, pursuit and arrest of the assassin of President Lincoln, obtained from unquestionable sources.

Of course, every member of the expedition, civil or military, regards himself as the principal agent, and some wonderful stories are told; but what I have stated may be relied upon as correct.

This is, however, but the second act in the great conspiracy, the first act of which cost us our President. Other arrests have been made.

Other arrests are to be made, and in due time the public will learn the extent and the deliberate wickedness of the whole crime. They will also see that much of what has been published about arrests of the party who attacked Secretary Seward and other matters are bosh: Colonel Baker has detected the criminal, and the Secretary of War, who knows the facts better than anyone else, gives him the credit.

Appearance of the Body.

Booth’s moustache had been cut off apparently with scissors, and his beard allowed to grow, changing his appearance considerably. His hair had been cut somewhat shorter than he usually wore it.

Booth’s body, which we have before described, was at once laid out on a bench and a guard placed over it. The lips of the corpse are tightly compressed, and the blood has settled in the lower part of the face and neck. Otherwise the face is pale and wears a wild, haggard look, indicating exposure to the elements and a rough time generally in his skulking flight. His hair is disarranged and dirty, and apparently had not been combed since he took his flight. The head and breast is alone exposed to view, the lower portion of his body, including the hands and feet, being covered with a tarpaulin thrown over it. The shot which terminated his accursed life entered on the left side at the back of the neck, a point, curiously enough, not far distant from that in which his victim, our lamented President, was shot.

A Spencer carbine, which Booth had with him in the barn at the time he was shot by Sergeant Corbett, and a large knife, with blood on it, supposed to be the one which Booth cut Major Rathbone with in the theatre box on the night of the murder of President Lincoln, and which was found on Booth’s body, have been brought to the city. The carbine and knife are now in the possession of Colonel Baker, at his office.

Booth had upon his person some bills of exchange, but only about $175 in Treasury notes.

The bills of exchange, which are for a considerable amount, found on Booth’s person, were drawn on banks in Canada in October last. About that time Booth was known to have been in Canada.

It is now thought that Booth’s leg was fractured in jumping from the box in Ford’s Theatre upon the stage, and not by the falling of his horse while endeavoring to make his escape, as was at first supposed.

The Captured Assassins.

The greatest curiosity is manifested to view the body of the murderer Booth, which yet remains on the gunboat in the stream off the Navy Yard. Thousands of persons visited the yard today in hopes of getting a glimpse at the murderer’s remains, but none were allowed to enter who were not connected with the yard. The wildest excitement has existed here all day, and regrets are expressed that Booth was not taken alive.

Sergeant Corbett.

It is said that in pulling the trigger upon Booth, he sent up an audible petition for the soul of the criminal.

The pistol used by Corbett was the regular large-sized cavalry pistol. He was offered a thousand dollars this morning for the weapon with its five undischarged loads.

An Autopsy.

This afternoon, Surgeon-General Barnes, with an assistant, held an autopsy on the body of Booth.

Booth Not in Rebel Uniform.

It now appears that Booth and Harold had on clothing which was originally of some other color than the Confederate grey, but being faded and dusty, presented that appearance.

Booth’s Mistress.

The news of Booth’s death reached the ears of his mistress while she was in a streetcar, which caused her to weep bitterly, and drawing a photograph likeness of the murderer from her pocket, kissed it fondly several times.

The Demeanor of Harold.

Harold, thus far, has evaded every effort to be drawn into conversation by those who have necessarily come in contact with him since his capture, but his outward appearance indicates that he begins to realize the position in which he is placed, and that there is no hope for his escape from the awful doom that certainly awaits him. His relations and friends, in this city, are in the greatest distress over the disgrace that he has brought upon himself.

Bowling Green.

Bowling Green, near which place Booth was killed, is a post village, the capital of Caroline county, Virginia, on the road from Richmond to Fredericksburg, forty-five miles north of the former, and is situated in a fertile and healthy region. It contains two churches, three stores, two mills and about three hundred inhabitants.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve during the Civil War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles: