Introduction: Mary Harrell-Sesniak is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background. In this guest blog post, Mary provides a fun quiz to test your knowledge of terms used in old newspapers to describe our ancestors’ occupations—and then provides illustrated definitions of those terms.

Genealogy research often finds terms used for occupations that are no longer common in today’s vernacular, such as: cordwainer, gaoler, huckster and suttler.

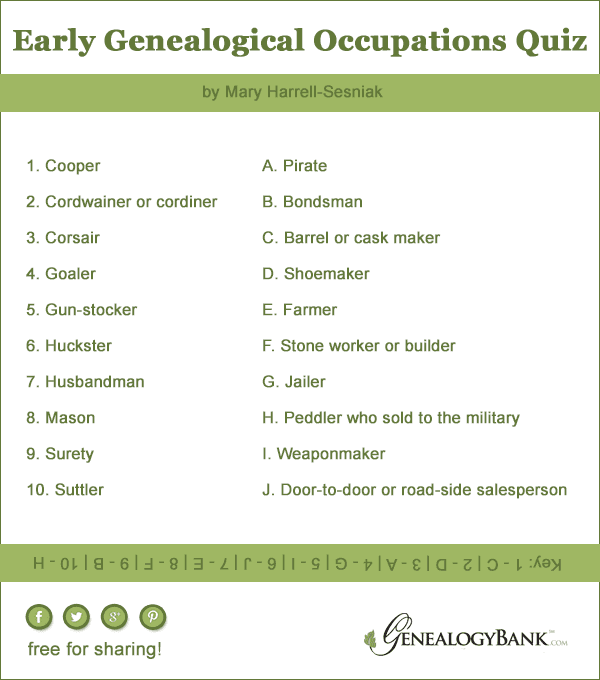

How well do you know the occupational terms used in old newspapers to identify our American ancestors’ jobs? Test your historical jobs knowledge with this handy Early Genealogical Occupations Quiz. Match the historical occupational names in the left column with the modern occupational name answers on the right. Check the key on the bottom to see how you did.

If you missed any of the answers on the Early Genealogical Occupations Quiz, read on to see a list of illustrated occupations I’ve compiled from Genealogybank’s archive of early American newspapers. You may be surprised at some of the historical job definitions.

If you missed any of the answers on the Early Genealogical Occupations Quiz, read on to see a list of illustrated occupations I’ve compiled from Genealogybank’s archive of early American newspapers. You may be surprised at some of the historical job definitions.

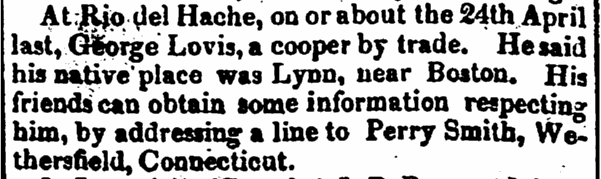

Cooper: In early America, coopers were barrel or cask makers and repairers, as seen in this 1825 death notice for George Lovis describing him as “a cooper by trade.”

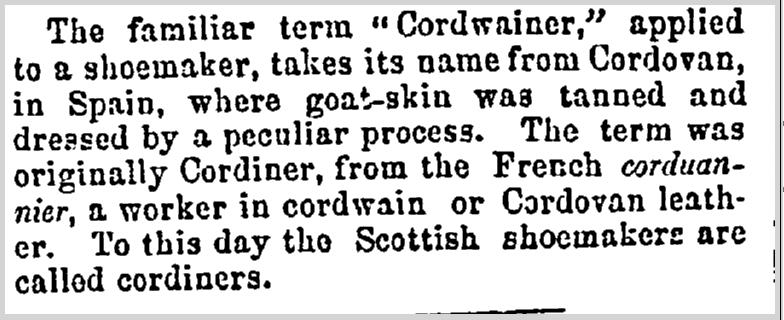

Cordwainer or Cordiner: Originating from the leather industry in Cordovan, Spain, a cordwainer was a shoemaker, as reported in this 1860 definition from the Salem Observer.

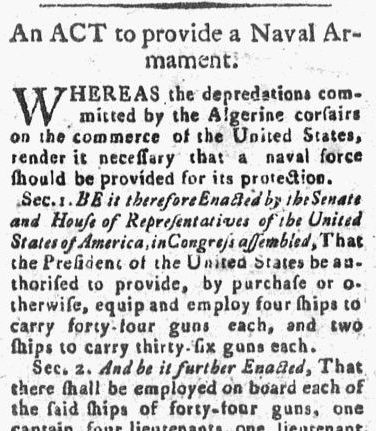

Corsair: A corsair was a pirate. A 1794 statute authorized the president of the United States to create a naval force to protect against Algerine corsairs, i.e., pirates from Algiers.

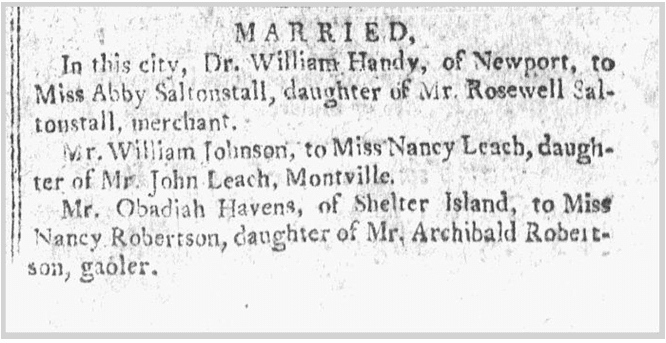

Gaoler: This was an early spelling of jailer, as reported in this 1799 marriage notice for Obadiah Havens and Nancy Robertson, the daughter of “Mr. Archibald Robertson, gaoler.”

Gentlemen and Goodwives: These words are based on the term “les gentils,” and indicated a “gentile” who owned freehold property. After the 16th century, the term referred more to one who did not work with his hands, or one who had retired from working with his hands (e.g., a retired tailor). A gentleman’s wife was commonly called Goodwife or “Goody.” Gentlemen typically had Esquire (Esq.) added to their names, even if they were not attorneys.

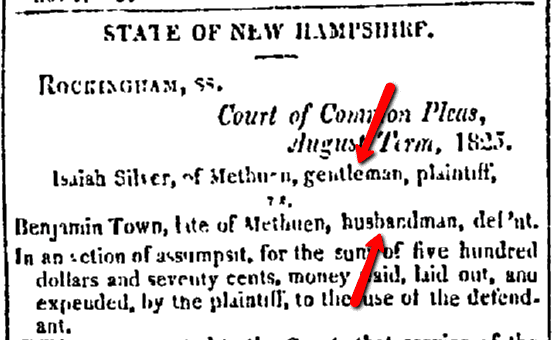

Husbandman: A husbandman was an early term for farmer, often of a lower societal class.

In this 1825 newspaper article, plaintiff Isaiah Silver of Methuen was described as a gentleman, and defendant Benjamin Town as a husbandman.

Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), 23 November 1825, page 4

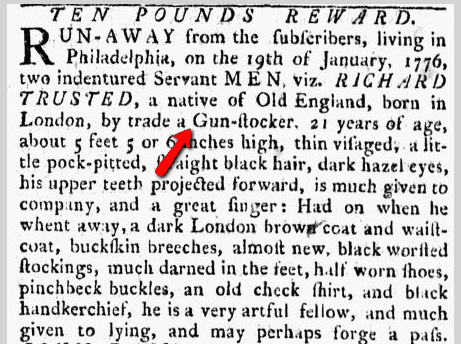

Gun Stocker: A gun stocker was a weapon maker, or someone who fitted wooden stocks to firearms. In this 1776 reward notice for run-away indentured servant Richard Trusted, the advertiser described him as a gun stocker by trade.

Huckster: A huckster was a door-to-door, road-side or kiosk salesperson, such as Eleanor Keefauver, a young woman who grew and sold her own vegetables in 1903.

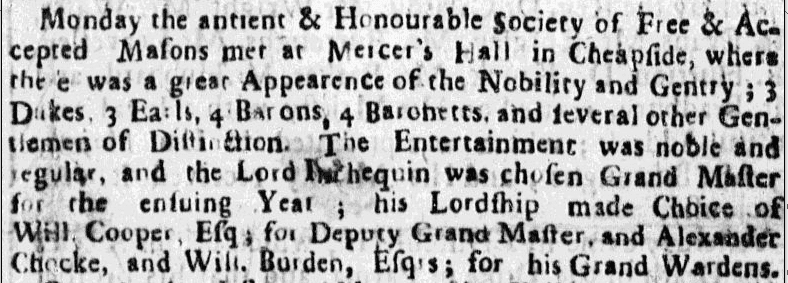

Mason: A mason was a builder, bricklayer or stone worker, a term still used today. Many people are intrigued by the mystery surrounding the “Ancient & Honourable Society of Free and Accepted Masons,” an international fraternal and charitable organization known for its secretive rites. One of the earliest references in GenealogyBank dates to 1727, describing a society meeting “where there was a great Appearance of the Nobility and Gentry.” (The gentry held a high societal status just below the nobility).

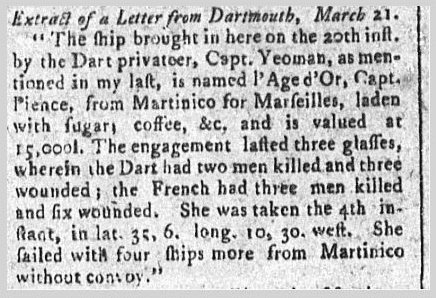

Privateer: A privateer was an armed ship, or the owner of the same, who was commissioned by the government to capture enemy ships—a form of legalized piracy. Privateers were often entitled to keep the bounty, known as a “prize.” This 1780 newspaper article reported that the privateer Dart brought a captured ship to Dartmouth.

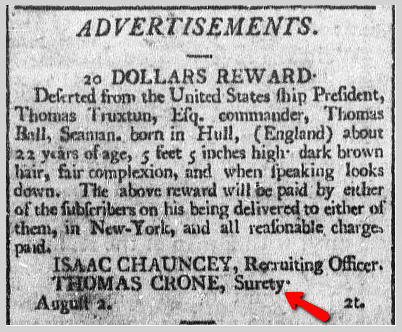

Surety: A surety was a bondsman or bonded individual who ensured that an event, such as a marriage, would take place. If the event did not occur, the surety encountered a financial loss. In this 1800 advertisement, surety Thomas Crone guaranteed payment of a reward for the return of Thomas Ball, a deserted seaman.

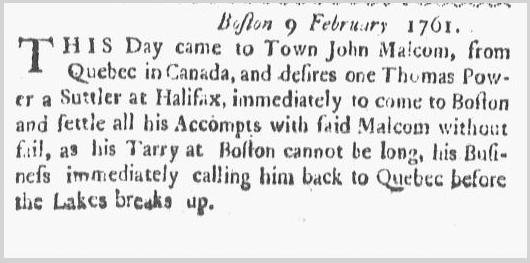

Suttler: Suttlers were peddlers who sold items to soldiers or the military. This 1761 newspaper notice reported that John Malcom “desires one Thomas Power, a Suttler at Halifax, immediately to come to Boston” to settle his accounts, because Malcom’s “tarry” (stay) at Boston would not be long; he needed to return to Quebec before the breaking up of the lake ice.

If you enjoyed these reports of historical occupations found in newspapers, watch for a follow-up in a future GenealogyBank blog article.

Did your ancestors have any unusual occupations? Share them with us in the comments.

In 1876 my great grandfathers occupation was a hooker. It was on his marrage license. I have no clue.

My grgrgrandmother, in 1885 city directory for Kansas City, MO, is listed with occupation “zephyr goods”. In another year she was listed as dressmaker, so I assume this is related somehow.

Ethel,

I’d love to know where you found that record. It’s possible he was a street-side solicitor or salesman!

Mary

Kansas City Star (Kansas City, MO), Sep. 12, 1888, p. 2 (excerpt):

THE UNION AVENUE “HOOKERS.”

One of the Many Queer Ways to Make a Living.

The following sign was conspicuously displayed in one of the windows of a cheap restaurant on Union avenue yesterday.

WANTED SOLICITOR FOR TRADE

… A number of applicants were seen to enter, and from the appearance of their countenances when they came out, it was evident they were not pleased with the employment offered.

A STAR reporter entered and asked a burly fellow seated behind a counter heaped up with pies and sandwiches about the position…

“Young feller, you don’t want this job. You aren’t built for a “hooker.”

The proprietor of the place then came up and explained the mysteries of the “hookers” employment. He stated that the “hooker’s” duty consisted of standing in front of the entrance of the restaurant and orating in a loud tone of voice that the best meals for a quarter in this city could be had within. If a country man, or as he puts it, a “Jay” happened along, it was incumbent on the “hooker” to grasp the country man’s arm, gently if he yielded, and forcibly if he resisted, and conduct him into the [illegible] place.

“Now, if I put up a sign for “hooker,” I’d never get a call, so I jest [sic] say, “Solicitors for trade”…

The “hooker” is a familiar figure on Union avenue. Nearly every saloon, auction joint and restaurant has one or more…

Another definition for hooker pertained to the mining industry.

Hookers were also miners who worked at the bottom of mine pits or shafts. Their duty was to secure (or hook) the newly filled corves [mining baskets or wagons], before they were taken to the surface.

i am doing ancestry and i have found an ancestor and their occupation is listed…….do, is that a doctor?

Generally “do” is the same as ditto, so look at what is written in the line above.

“do” was the abbreviation for “same as above”; today we just use ditto marks “

I found one of the articles on Shelter Island particularly insightful since I know the both the Havens and Archibald families! Funny, it is a small world!

Mary,

I just wanted to let you know that your blog post is listed in today’s Fab Finds post at http://janasgenealogyandfamilyhistory.blogspot.com/2013/03/follow-fridayfab-finds-for-march-22-2013.html

Have a great weekend!

Jana,

Thank you for including the blog article in your Fab Finds list. I appreciate it very much.

Mary

In a US census a relative’s occupation was a “carbiner”. I have not been able to find what this was.

What was a “platform man”? 1920’s.

If you could supply the census reference for carbiner, we could narrow the options.

One definition would be rifleman, or someone who operated a carbine, or short rifle or musket. They were also known as carabiners, and a synonym would be cavalry soldier.

A carabiner is also a device used to secure ropes in rock climbing, so there could be a relationship. To narrow down the meaning, review the census for others in the same vicinity, who either worked in the military or a heavy industry, such as mining.

I’m not certain of the definition for platform man, but it may have been a loader, or person who assisted on a railroad or warehouse platform.

Hugh Starkey was a teamster just before the Civil War.

I have seen the occupation “stripper” in city directories. It did take me aback for a minute, until I noticed that it seemed to be related to cigar-making!

Darlene,

Always fun to see old terms with their modern day associations!

Mary