Introduction: In this article, Katie Rebecca Garner gives tips for finding records and learning the stories about your immigrant ancestors. Katie specializes in U.S. research for family history, enjoys writing and researching, and is developing curricula for teaching children genealogy.

Aside from what remains of the indigenous population, the U.S. is peopled with immigrants and descendants of immigrants. Some immigrant ancestors are as recent as parents or grandparents, while other immigrant ancestors go as far back as colonial times. No matter when your immigrant ancestors came to America, they left records behind. Searching these records can give you insight into their travel experience and life in the new country.

Since the earliest immigrant settlements in America, combinations of push factors from the home country and pull factors to America led our ancestors here. Push factors included religious persecution and disbandment of the feudal system. Pull factors included land ownership, freedom, and opportunity. Some people were forced to emigrate, such as convicts and slaves. To learn the historical context around why your ancestor emigrated, look up your ancestor’s homeland in the FamilySearch wiki.

Many different emigration patterns occurred. Those who were too poor to afford passage became indentured servants so that another would pay their passage. Some families would send the father or eldest sons to America to work to pay passage for the rest of the family. Religious groups fleeing persecution emigrated together. Those who were the first in their community to emigrate often wrote home about how wonderful America was, prompting those they left behind to follow them.

Because many of these patterns involved multiple people in a community or family group, FAN (friends, associates, neighbors) club research is an effective strategy for immigration research.

Clues about Immigration

The first clue about an immigrant ancestor is any record stating their birthplace in another country. This includes censuses, death records, military records, church records, and marriage records. Sometimes the clues of immigration are found in records of the children of the immigrant, such as census records and death certificates which ask for the parents’ birth places.

The next thing to determine is when and where the ancestor arrived in the U.S. If the ancestor naturalized, those records would contain arrival information. If no record states the ancestor’s arrival, you can estimate it based on their first appearance on records in the U.S.

If the immigrant ancestor naturalized after 1906, the naturalization records will have asked for the port and date of arrival, which will make it easier to find the ancestor on a passenger list. Naturalization records before 1906 were inconsistent so there’s no guarantee they’ll lead you to the passenger list.

County histories of the places your ancestors lived usually contain information about early settlers and prominent citizens. This may include immigration information.

Finding the Immigration Records

If you have records stating the immigration port and date of arrival, finding the passenger list is as simple as searching that port at that date. If you do not know the immigration port, multiple ports may need to be searched and guesswork may need to be used to prioritize the likelihood of each immigration port. While there are searchable databases for multiple ports, such databases usually are not comprehensive.

Start by searching the port closest to where the ancestor lived or settled. It may also be helpful to know which ports were the most popular at the time your ancestor immigrated. The following table provides a reference to major ports’ establishment and prominence.

| 1625 | Port of New York established by Dutch |

| 1630 | Port of Boston founded |

| 1630-1750 | Port of Boston most prominent |

| 1682 | Port of Philadelphia founded, competes with port of Boston |

| 1718 | Port of New Orleans founded by French |

| 1729 | Port of Baltimore founded |

| 1762-1803 | Port of New Orleans controlled by Spanish |

| 1803 | U.S. gains control of New Orleans port |

| 1840-1861 | New Orleans 4th most prominent port |

| 1825 | Erie Canal completed, port of New York becomes busiest port |

The passenger lists often include the destination city and former hometown. If families traveled together, they may be listed together on the passenger list. Information on passenger lists was more consistent after 1906 when the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization was established. Before then the information contained on these lists was based on what the ship captain wanted to include.

Border Crossings

If an immigrant ancestor came over from Canada or Mexico, they would have gone through a border crossing checkpoint instead of a port of entry. Sometimes immigrants found it more cost-effective to sail to Canada, then take a train into the U.S. If you are not finding your ancestor in a passenger list, try searching border crossing records and Canadian ports.

Finding the Hometown

To research an ancestor in the old country, it is necessary to know the ancestor’s hometown. If the ancestor immigrated or naturalized after 1906, their immigration or naturalization records would contain their hometown. However, if the ancestor immigrated and naturalized before 1906, the hometown is less likely to be in those records and must be searched for in other records, including: obituaries, marriage records, draft registration, pension records, newspapers, and family Bibles.

Name Changes

When a family emigrated from a non-English speaking country to America, they may have anglicized their names. Even if the family did not, it is likely that their names may have been misspelled, mispronounced, and misunderstood throughout their lives in America. This is especially likely before the family learned English.

An example of this is the Trankina family, who immigrated to the U.S. from Italy around the late 1800s. Their surname is spelled differently on every census they were enumerated on and in other records: Frankina, Trankino, Franchinco, Tranchina. Additionally, being able to identify them on records required knowing both the English and Italian versions of their given names. Behindthename.com is a website good for learning other languages’ versions of given names.

Your immigrant ancestor embarked on an adventure to start a life in America. You are American because of each of your immigrant ancestors. It is your turn to embark on an adventure: the adventure of learning your immigrant ancestor’s story!

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

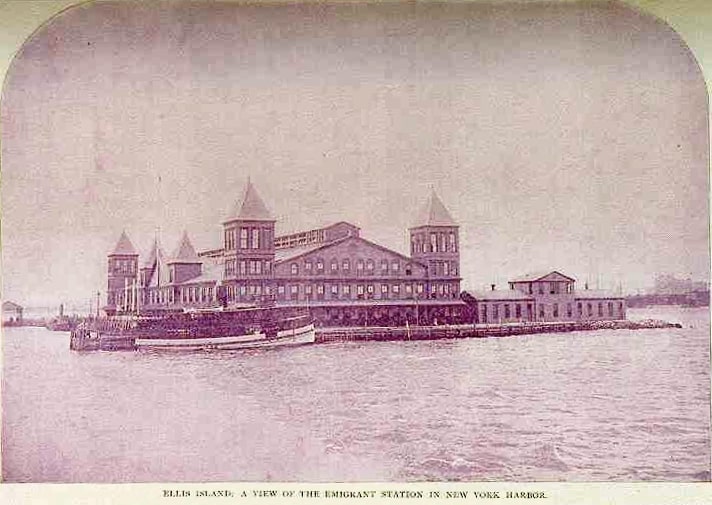

Note on the header image: immigrants coming up the board-walk from the barge, which has taken them off the steamship company’s docks, and transported them to Ellis Island, 1902. Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Resources:

- Family Search: United States Emigration and Immigration

- FamilySearch: Ports of Arrival