When ex-president and general Dwight D. Eisenhower died on 28 March 1969, America lost one of its true heroes, a man who played an enormously important role in the nation’s history during the middle of the 20th century. A five-star general, Eisenhower was the Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe during World War II. In 1951 he served as the first Supreme Commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Then in 1953 he became the country’s 34th president, ably serving for two terms – winning his second term in a landslide, as by then practically the entire nation seemed to agree with the slogan of his 1952 presidential campaign: “I like Ike.”

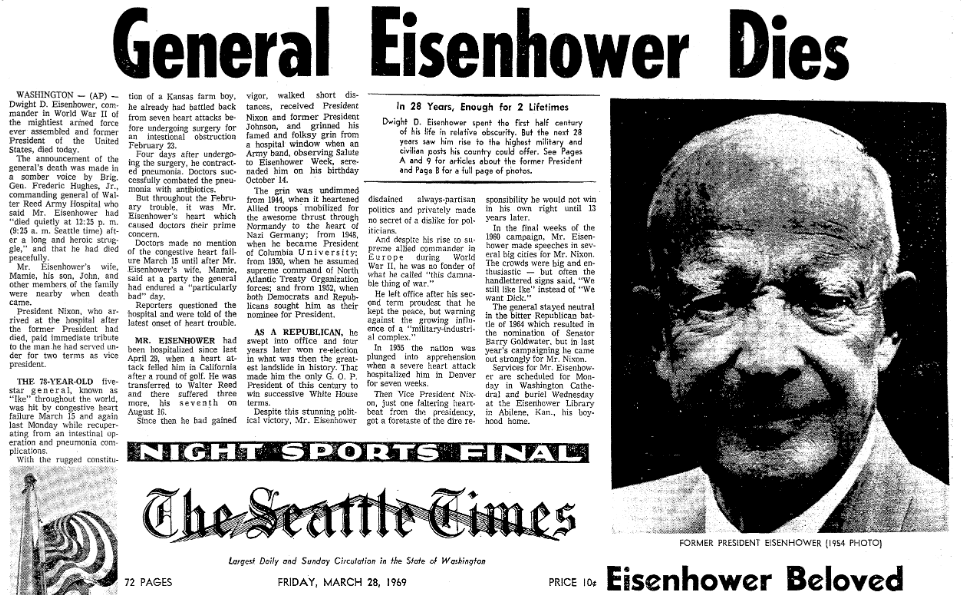

The following two newspaper articles were written on the occasion of Eisenhower’s passing. The first is a news report announcing his death, and the second is an article emphasizing how well-liked and admired Eisenhower was, not just in the United States but around the world.

Here is a transcript of this article:

General Eisenhower Dies

Washington (AP)—Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander in World War II of the mightiest armed force ever assembled and former President of the United States, died today.

The announcement of the general’s death was made in a somber voice by Brig. Gen. Frederic Hughes, Jr., commanding general of Walter Reed Army Hospital, who said Mr. Eisenhower had “died quietly at 12:25 p.m. (9:25 a.m. Seattle time) after a long and heroic struggle,” and that he had died peacefully.

Mr. Eisenhower’s wife, Mamie, his son, John, and other members of the family were nearby when death came.

President Nixon, who arrived at the hospital after the former President had died, paid immediate tribute to the man he had served under for two terms as vice president.

The 78-year-old five-star general, known as “Ike” throughout the world, was hit by congestive heart failure March 15 and again last Monday while recuperating from an intestinal operation and pneumonia complications.

With the rugged constitution of a Kansas farm boy, he already had battled back from seven heart attacks before undergoing surgery for an intestinal obstruction February 23.

Four days after undergoing the surgery, he contracted pneumonia. Doctors successfully combated the pneumonia with antibiotics.

But throughout the February trouble, it was Mr. Eisenhower’s heart which caused doctors their prime concern.

Doctors made no mention of the congestive heart failure March 15 until after Mr. Eisenhower’s wife, Mamie, said at a party the general had endured a “particularly bad” day.

Reporters questioned the hospital and were told of the latest onset of heart trouble.

Mr. Eisenhower had been hospitalized since last April 29, when a heart attack felled him in California after a round of golf. He was transferred to Walter Reed and there suffered three more, his seventh on August 16.

Since then he had gained vigor, walked short distances, received President Nixon and former President Johnson, and grinned his famed and folksy grin from a hospital window when an Army band, observing Salute to Eisenhower Week, serenaded him on his birthday October 14.

The grin was undimmed from 1944, when it heartened Allied troops mobilized for the awesome thrust through Normandy to the heart of Nazi Germany; from 1948, when he became President of Columbia University; from 1951, when he assumed supreme command of North Atlantic Treaty Organization forces; and from 1952, when both Democrats and Republicans sought him as their nominee for President.

As a Republican, he swept into office and four years later won re-election in what was then the greatest landslide in history. That made him the only G.O.P. President of this century to win successive White House terms.

Despite this stunning political victory, Mr. Eisenhower disdained always-partisan politics and privately made no secret of a dislike for politicians.

And despite his rise to supreme allied commander in Europe during World War II, he was no fonder of what he called “this damnable thing of war.”

He left office after his second term proudest that he kept the peace, but warning against the growing influence of a “military-industrial complex.”

In 1955 the nation was plunged into apprehension when a severe heart attack hospitalized him in Denver for seven weeks.

Then Vice President Nixon, just one faltering heartbeat from the presidency, got a foretaste of the dire responsibility he would not win in his own right until 13 years later.

In the final weeks of the 1960 campaign, Mrs. Eisenhower made speeches in several big cities for Mr. Nixon. The crowds were big and enthusiastic—but often the hand-lettered signs said, “We still like Ike” instead of “We want Dick.”

The general stayed neutral in the bitter Republican battle of 1964 which resulted in the nomination of Senator Barry Goldwater, but in last year’s campaigning he came out strongly for Mr. Nixon.

Services for Mr. Eisenhower are scheduled for Monday in Washington Cathedral and burial Wednesday at the Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kan., his boyhood home.

Here is a transcript of this article:

Eisenhower Beloved in War and Peace

By Robert J. Donovan

Los Angeles Times

Washington—If it had not already been said of George Washington, it could well be said of Dwight D. Eisenhower that he was in his day first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.

In World War II he led the greatest military machine in history to victory in Europe. After the war and his election as President, he was regarded throughout the world as the greatest peacemaker of his time. As supreme allied commander in Europe he had won the hearts of his countrymen, and as President and ex-President he never lost his claim to those hearts.

Dwight Eisenhower was not the greatest of all soldiers nor the shrewdest of all statesmen nor yet the wisest of all Presidents. Among the American people of his time, however, he was exalted as few men have been in the history of the United States.

Political opponents, critical journalists, foreign diplomats, scholars and various sophisticated men and women detected from time to time all sorts of mistakes, follies, banalities and muddle-headed notions in the Eisenhower way of doing things.

To masses of people, however, he seemed warm, kind, trustworthy, sensible, altruistic, patriotic, protective and deeply devoted to duty. It was these qualities combined with his mature good looks and manly bearing that gave him what was fashionable to call “the father image.” This father image, or whatever it was, made him impregnable on election day.

The irony of his presidency was that he wanted to pause and preserve some of the traditional values and traditional methods only to be confronted by a time of irresistible and accelerating change.

It was not that Mr. Eisenhower was a stand-patter and certainly not that he was a reactionary. But taking office after the country had gone through the loop-the-loops of the Great Depression, World War II, the Fair Deal, the Cold War and Korea, he believed that the time had come to consolidate.

Furthermore he trusted in old concepts like the balanced budget, states’ rights, local responsibility and the separation of powers between the President and the Congress.

Holding office in the interval between Mr. Roosevelt and Mr. Truman before him and Mr. Kennedy and Mr. Johnson afterward, he provided an oasis of orthodoxy in mid-20th century. He did not reach for power as did the Democratic Presidents whose administrations framed his own. His background, temperament and inexperience in domestic politics militated against it.

Although Mr. Eisenhower strove to preserve old and honored concepts, he was scarcely out of office before they were swept aside by the modern tide that brought planned deficits, Medicare, Federal aid to education, Washington’s war against poverty and federal involvement in the Negro problem everywhere.

By the standards of the social revolution that followed him Mr. Eisenhower already seems an old-fashioned President.

In other respects, however, this view is misleading. Mr. Eisenhower was far more progressive than many elements of his own party. He had a much greater breadth of vision than most of the Republican congressional leaders and the G.O.P. Old Guard.

He did a great deal to modernize the outlook of a Republican Party that had stood for isolation before World War II and had blindly fought the domestic reforms of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Unlike some Old Guard Republicans, President Eisenhower accepted the New Deal reforms, including Social Security, collective bargaining, the minimum wage and federal-welfare grants. Indeed he expanded certain of these programs and initiated a huge federal highway-building project of New Deal proportion.

His experiences in war-torn Europe and later as the first commander of the post-war North Atlantic Treaty Organization forces caused Mr. Eisenhower to despise the hostility of Republican conservatives toward foreign aid.

On the whole Mr. Eisenhower carried forward the foreign policies of the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, even though he had to drag some Republican members of Congress kicking and screaming after him.

Mr. Eisenhower was not an innovator. Doubtless he saw no need for innovation. Though his prudence may have held him back from scaling heights that rise above all Presidents, it also kept him out of the kind of abyss into which President Johnson tumbled in Vietnam.

Thus when Mr. Eisenhower came under intense pressure to assist the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, he resisted because this country’s World War II Allies would not join in the venture.

Mr. Eisenhower took the presidency in stride. There was nearly always a time for some bridge or golf. He had none of the zest for the office that John F. Kennedy was to display, nor did he labor at it night and day as Lyndon Johnson was to do.

Conditioned by his military experience, Mr. Eisenhower delegated a good deal of authority—mainly to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles in the foreign field, and to Sherman Adams, the assistant to the President, and to Secretary of the Treasury George M. Humphrey in domestic affairs.

In an office that often compels its occupant to turn in upon himself in times of trouble, Mr. Eisenhower remained an extrovert. He was more likely to become garrulous than withdrawn.

Mr. Eisenhower never possessed the kind of technical-political skills exercised by Presidents like Franklin D. Roosevelt or Lyndon B. Johnson. In compensation, however, he had a perfect genius for making people admire him, even when they knew next to nothing about him personally. “We Like Ike” was the truest campaign slogan ever coined.

Related U.S. Presidents Articles: