Introduction: In this article, Katie Rebecca Garner continues her series examining newspapers in various regions of the U.S. – and how helpful they are for your genealogy – focusing on newspapers in the Southeast area. Katie specializes in U.S. research for family history, enjoys writing and researching, and is developing curricula for teaching children genealogy.

Social media is used today to keep track of what’s happening in the world. Our ancestors used newspapers for the same reason. One way to learn about our ancestors is through their social media: newspapers.

Many courthouses in the South were burned in the Civil War, destroying records genealogists rely upon. Fortunately, small town newspapers reported everything, making them a useful resource for Southern genealogy.

Newspapers published notices of marriages, divorces, deaths, and funerals. Such notices contain the names of the people involved and the date of the event; they may also include names of relatives, maiden names, and additional information about the ancestor.

Today we’ll focus on newspapers from the Southeast region of the United States. At the end of this article, I’ll present a genealogy case study from one of the newspapers in this area to show just how helpful these papers can be to your own family history research.

- Alabama’s earliest newspaper, the Mobile Sentinel, was published in 1811 in Fort Stoddert.

- Florida’s first newspaper was published in 1783 by a Tory wanting to announce the end of the American Revolution. This newspaper was discontinued when Florida went under Spanish rule. The Florida Gazette began in 1821 in St. Augustine after Florida went back under USA control.

- Georgia’s earliest newspaper, the Georgia Gazette, was published in Savanna beginning in 1763.

- Mississippi’s first newspaper, the Mississippi Gazette, was published in Natchez in 1799.

- South Carolina’s first newspaper, the South Carolina Gazette, was published in 1732.

Thanks to the internet, many newspapers are available online, including the more than 13,000 newspapers available in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives

GenealogyBank’s newspapers are divided into two collections, each with its own search page:

- Newspaper Archives (complete paper with all articles, including historical obituaries, with a number of very rare single-issue newspapers – many of them are the only known issues of the paper)

- Obituaries (including both historical and recent obituaries, if obits are specifically what you are searching for)

GenealogyBank currently has the following from the Southeast states:

- Alabama: 146 newspapers, including newspaper archives and obituaries from 1813 to the present

- Florida: 282 newspapers, including newspaper archives and obituaries from 1783 to the present

- Georgia: 215 newspapers, including newspaper archives and obituaries from 1763 to the present

- Mississippi: 318 newspapers, including newspaper archives and obituaries from 1802 to the present

- South Carolina: 261 newspapers, including newspaper archives and obituaries from 1735 to the present

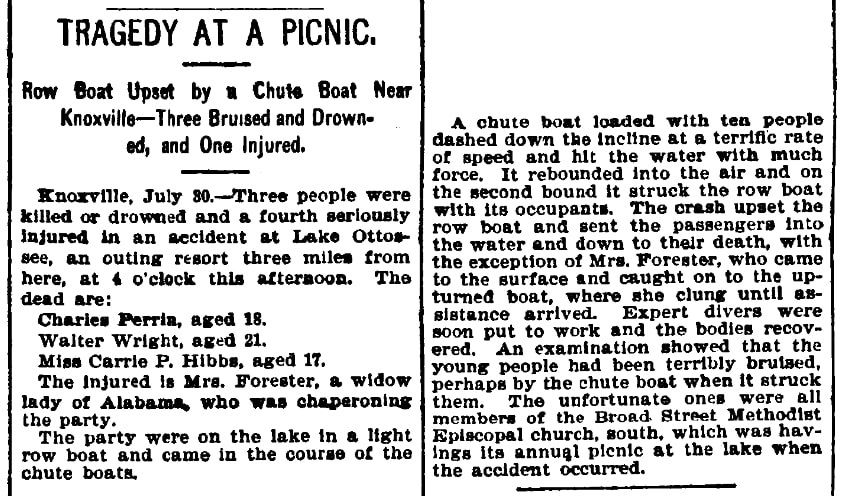

Case Study: A Tragedy at a Picnic

A newspaper article published in the Birmingham State Herald announced the deaths of three young people in a boat accident in Lake Ottossee in Tennessee. The news, coming from Knoxville on 30 July 1896, was published in Birmingham, Alabama, the next day.

There is a Knoxville, Alabama, as well as a Knoxville, Tennessee. Knoxville, Alabama, is closer to Birmingham than Knoxville, Tennessee. However, Lake Ottossee is near Knoxville, Tennessee. Using maps in research can help to avoid confusion.

The article details the accident. Importantly for family historians, it gives genealogically valuable information about the three boaters who died. The names and ages of the drowned youths are given, so their birth years can be calculated as follows:

- Charles Perrin, age 18, born 1878

- Walter Wright, age 21, born 1875

- Carrie P. Hibbs, age 17, born 1879

The article also mentions the church they belonged to, which can be very helpful in research. The youths and their chaperone, Mrs. Forester (identified as “a widow lady of Alabama”), belonged to the Broad Street Methodist Episcopal Church, South.

Not all church records are online. Searching church records offline requires knowing the location and denomination, then contacting either the church or a local genealogical society. This may be necessary for finding church records for these people because I couldn’t find their church records online.

I found the death register for the drowning victims. All three are listed together in the Knoxville death register with the death date of 30 July 1896. Despite some discrepancies, they are obviously the same people who drowned in the boating accident. Variances in name spelling and reported age are not uncommon in genealogy research.

Since the three youths were born in the 1870s, they appeared as young children on the 1880 census. Multiple possible results appeared for each boy, each of different races. Because our modern society frowns on racism and celebrates diversity, a group of youths boating today could be of various races. But in the 1890s racial discrimination was common and legal, especially in the South. Therefore, it is safe to assume that everyone in that boat was the same race.

I only found one search result in the 1880 census for Carrie Hibbs, located in Stewart County, Tennessee, and her family was white. (No Carrie “Phibbs” was found, suggesting her surname was misspelled in the Knoxville death register.) Based on this evidence, we can assume the other boat passengers were also white.

I also found a Charles R. Perrin in the 1880 census, located in Grainger County, Tennessee.

Keeping in mind that Charles Perrin was listed as “Chas Perry” in the Knoxville death register, I searched the 1880 census for that alternative spelling of his surname.

I found a Charley Perry, age four (born 1876), in Fayette County, Tennessee. (1) Charles R. Perrin matches the name spelled in the newspaper article, and Charley Perry matches the name spelled in the death register.

Only looking at names, dates, and places doesn’t give us enough information to determine which boy listed in the census was the boy involved in the accident.

However, there’s this important distinction: the Perrin family in Grainger County was white and the Perry family in Fayette County was black and mulatto. Charley Perry was probably too dark to be in a boat with white people in Tennessee in 1896. Therefore, it is safer to assume that Charles R. Perrin is the same Charles Perrin that drowned in the boating accident.

I found two search results for the third drowning victim, Walter Wright, both born in 1875. One was white and living in Obion County, Tennessee. (2) The other was mulatto and living in Trousdale County, Tennessee. (3)

Mulatto people could pass for either white or black depending on how light or dark their skin was. The mulatto Wright family would need to be found on other records to make a guess about how likely they could have passed for white. The mulatto Walter Wright could have been on that boat if he was light enough, but it seems more likely that the white Walter Wright was the one on the boat. Further research can support these assumptions.

Your ancestors may not have had deaths as dramatic as Walter, Charles, and Carrie, but newspapers could still be helpful in researching your Southeast ancestors.

Resources:

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Alabama_Newspapers

- https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Georgia_Newspapers

- https://wiki.rootsweb.com/wiki/index.php/South_Carolina_Periodicals,_Newspapers,_and_Manuscript_Collections

- https://wiki.rootsweb.com/wiki/index.php/Mississippi_Periodicals,_Newspapers,_and_Manuscript_Collections

- https://wiki.rootsweb.com/wiki/index.php/Alabama_Periodicals,_Newspapers,_and_Manuscript_Collections

- https://wiki.rootsweb.com/wiki/index.php/Florida_Periodicals,_Newspapers,_and_Manuscript_Collections

__________________

(1) U.S. 1880 census, Fayette County, Tennessee, population schedule, 29th enumeration district (indexed as District 13), p. 48 (penned), dwelling 512, family 514, Charley Perry in household of Frulan Perry; digital image, GenealogyBank, (https://genealogybank.com: accessed 31 August 2022), citing FamilySearch collections.

(2) U.S. 1880 census, Obion County, Tennessee, population schedule, Civil District no 16 (indexed as Pierces and Fulton Station), p. 4 (penned), dwelling 30, family 30, Walter C. Wright in household of A. J. Wright; digital image, GenealogyBank, (https://genealogybank.com: accessed 31 August 2022), citing FamilySearch collections.

(3) U.S. 1880 census, Trousdale County, Tennessee, population schedule, Corleys School House, p. 14 (penned), dwelling 111, family 114, Walter Wright in household of James Wright; digital image, GenealogyBank, (https://genealogybank.com: accessed 31 August 2022), citing FamilySearch collections.

Related Articles: