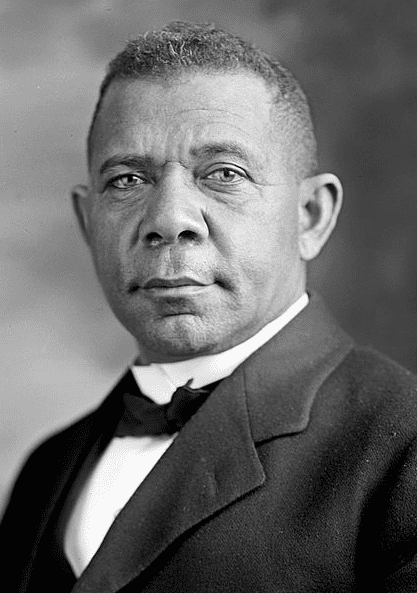

On 14 November 1915, at the age of 59, educator, author, and African American leader Booker Taliaferro Washington died. He was buried on the campus of his beloved Tuskegee University in Alabama, an institution that exemplified everything Washington believed in: advancement of the African American race through education and hard work. He was that school’s first principal when the “Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute” opened on 4 July 1881, and held that position the rest of his life.

Washington’s life story is an astonishing tale of commitment, dedication and hard work. Born a slave on a Virginia plantation in 1856, he went on to become the leading African American voice of his day, with many friends both black and white, North and South. He authored 14 books, was awarded honorary degrees from such premier schools as Harvard and Dartmouth, was befriended by many wealthy benefactors and philanthropists, was an adviser to U.S. presidents, and led a crusade that built thousands of schools throughout the rural South to provide education to African Americans.

Washington was only nine years old when he and his family were emancipated by the ending of the Civil War in 1865. He labored in coal mines and salt furnaces in West Virginia for several years, assiduously saving his meager wages to fund his own education. When he had saved enough money, he journeyed east to Hampton Institute in Virginia, a school for freedmen, where he vigorously applied himself to his studies while continuing to work to cover his expenses. He later attended Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C., taught Sunday school at African Zion Baptist Church, then returned to Hampton as a teacher.

The president of Hampton Institute, Samuel C. Armstrong, was so impressed with the young Washington that he recommended he be appointed the principal of the new Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The 25-year-old Washington accepted, and led Tuskegee from its humble beginnings in a small shanty with $2,000 to – by the time of his death in 1915 – a thriving institution with nearly 100 buildings on a 3,500-acre campus with an endowment of $1.5 million.

Though he was widely admired and respected, Washington was not without controversy. He counseled blacks to accept the segregation and restrictions of the Jim Crow era in the post-Reconstruction South, arguing that by focusing on their education, working hard and accumulating wealth, African Americans would eventually win acceptance by white society. His advice to blacks was to gain equal civil rights through “industry, thrift, intelligence and property.”

Toward the end of Washington’s life other African American leaders, such as W. E. B. Du Bois of the NAACP, urged blacks to actively protest Jim Crow segregation and criticized Washington for being “the Great Accommodator.” Washington refused to abandon his core beliefs, however, convinced that confrontation would not gain greater freedom for African Americans: cooperation, education and hard work were the only answers. To his dying day, Washington believed that the best way for blacks to win acceptance by white society was “by showing themselves to be responsible, reliable American citizens.”

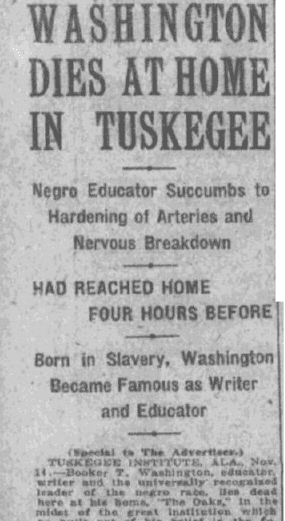

Here is a transcription of this article:

Washington Dies at Home in Tuskegee

Negro Educator Succumbs to Hardening of Arteries and Nervous Breakdown

Had Reached Home Four Hours Before

Born in Slavery, Washington Became Famous as Writer and Educator

(Special to The Advertiser.)

TUSKEGEE INSTITUTE, ALA., Nov. 14. – Booker T. Washington, educator, writer and the universally recognized leader of the negro race, lies dead here at his home, “The Oaks,” in the midst of the great institution which he built out of his belief in the future of his race and to see which, pilgrims have come from all parts of the earth.

Dr. Washington’s passing was as simple as the life which he had lived. Realizing that the end was near, he asked that he be brought from New York to the South – the South in which he had been born in, and for which he had labored, and where he had always declared his intention to die and be buried. And, so, with his wife, Dr. J. A. Kenney of the Tuskegee Institute, and his stenographer, Nathan Hunt, the long trip was begun.

When Chehaw, Alabama, was reached, where passengers change for Tuskegee, he was aroused by his wife, who said: “Father, this is Chehaw.” He answered and roused himself with great effort; and when Booker Washington, Jr., appeared, asked: “How is Booker?” meaning young Booker’s infant son.

Then began the slow but careful auto trip to the institute; but earth for Booker Washington was receding fast and soon unconsciousness came. At 4:45 o’clock this morning, surrounded by the members of his family who were present, the families of one son and daughter being absent, the distinguished negro leader breathed his last.

Funeral Program

The funeral exercises will be held on the institute grounds, Wednesday morning at 10 o’clock, and the body will be buried on the grounds of the school to build which his life has been given. The remains will lie in state in the institute chapel from 12 o’clock midday Tuesday until Wednesday, November 17.

Telegrams of condolence from all parts of the world are pouring into the school.

Through the years, it has been the ideal of organization and efficiency here that nothing shall disturb the orderly working of all parts of the institution. So far as the letter of this ideal is concerned, nothing is out of gear at Tuskegee; but the spirit broke down – broke down completely when the man who founded Tuskegee passed away this morning. Mechanically, bells, calling the school to its duties, have been rung and routine work taken up, but the heart is out of things. From the humblest pupil up through the faculty and the bereaved family at the institute, to the white and colored citizens of the town of Tuskegee, there is the feeling of personal loss. Nobody is hiding his tears. Nobody is free from gloom. Nobody can talk about the great loss which the school, the race and the country have sustained.

Silently, the student lines formed for Sunday morning inspection for chapel service; but there was no band music for the parade grounds: and yet in the quiet and calm of the Sabbath day, the band played a sacred march to the chapel, because the principal would have had it so.

The Sunday morning sermon by Chaplain Whittaker was in behalf of “Bleeding Armenia,” because it was what the late Dr. Washington had wanted done. But the sweetness was gone from the songs of the students today; and when the choir sang: “Still, Still with Thee,” hearts broke.

Believed in the South

Booker Washington’s life was dedicated to the education and uplift of his race and the promotion of better relations between negroes and whites throughout the country.

In season and out, he carried the message of economic fitness for the negro out of peace between the races. In particular, he hoped, he believed that in the South the negro would, at last, find his greatest opportunity; and he was, to the end, a friend of the South. With his passing, this section and the whole country has lost a great friend.

The Tuskegee educator’s life was replete with many unselfish activities in behalf of his race. Possessing rare executive and constructive ability, he devoted himself with much self-sacrifice to the upbuilding and regenerating of his race along moral, material and educational lines. The National Negro Business League, composed of negro business men and women, is the product of his creative genius and has come to a place of commanding influence in the life of the negro people.

He is survived by his wife; a brother, John H. Washington, superintendent of industries; three children and four grandchildren.

The negro leader had been in failing health for several months prior to his death; but he would not relax his activities. During the month of September, he spent a week on Mobile Bay fishing and resting and appeared to be greatly strengthened by the outing. His reserve strength, however, was not equal to the increasing burdens in the interest of the Tuskegee Institute and of his race.

On the 23rd of October, he left here to attend the annual meeting of the American Missionary Association which was held in conjunction with the National Conference of Congregational Churches, and on the evening of October 25th, spoke before this meeting. This was his last public appearance.

Tributes to His Life

William G. Willcox, treasurer of the Investment Committee of the Board of Trustees, sent the following telegram to Secretary Emmett J. Scott:

“Please express my deepest sympathy to all the teachers and pupils of the Institute in their great loss. Dr. Washington’s death is a national calamity, but his spirit will still live to inspire and carry forward his great work; and those left behind must bravely and loyally take up the great trust which now falls upon their shoulders.”

Emmett J. Scott, the confidential secretary of the deceased for eighteen years, said, speaking of him:

“The glory of the life which came to an end here this morning was its dedication to the service of both races, North and South. He will be remembered as an educational enthusiast whose sympathies and activities were broad enough to include all races and all movements looking to the betterment of mankind.”

Isaac Fisher, president of the Tuskegee Alumni Association, said:

“With the death of Dr. Washington, closes one complete chapter of negro history. The whole world is poorer today because he has gone.”

Treasurer Warren Logan, with Dr. Washington almost since the founding of the school, is acting principal.

Born in Slavery

Washington was born in slavery near Hale’s Ford, Va., in 1857 or 1858 [1856 – ed.]. After the emancipation of his race he moved with his family to West Virginia. He was an ambitious boy and saved his money for an education. When he was able to scrape together sufficient funds to pay his stagecoach fare to Hampton, Va., he entered General Armstrong’s School for Negroes there and worked his way through an academic course, graduating in 1875.

Later he became a teacher in the Hampton Institute, where he remained until 1881, when he organized an industrial school for negroes at Tuskegee. He remained principal of this school up to the time of his death.

The Institute started in a rented shanty church and today it owns 3,500 acres of land in Alabama and has nearly 100 buildings valued at half a million dollars.

Washington won the sympathy and support of leading Southerners by a speech in behalf of his race at the Cotton States Exposition in Atlanta in 1895. Of undoubted ability and breadth of vision, his sane leadership enabled him to accomplish more for and among the negroes of the United States than any negro of his time.

Roosevelt Incident

In addition to his prominence as an educator, Washington gained considerable fame as an author. He received an honorary degree of master of arts from Harvard University in 1896, and was given an honorary degree of doctor of laws by Dartmouth College in 1901.

An incident of Washington’s career made him a figure of national prominence during the administration of President [Theodore] Roosevelt. He sat down to lunch with the President at the White House either by formal or informal invitation. There was a storm of protest, particularly from the South, but in spite of the resulting hostility shown toward him by many white persons, Washington continued to exert a widespread influence toward the betterment of his people.

Note: There are more than 230 million obituaries in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, providing life stories and family information essential for genealogy research. Come take a look today, and see what you can discover about your ancestors.

Related Articles: