Introduction: In this article – the third in a series of three articles celebrating Thanksgiving – Jane Hampton Cook shows how Thanksgiving Day migrated to the South. Jane is a presidential historian and author of ten books, including her new book Resilience on Parade: Short Stories of Suffragists & Women’s Battle for the Vote. She is the author of Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. She was the first female White House webmaster (2001-03). Her works can be found at Janecook.com.

I have fond memories of frequently traveling from my home in Texas to my grandmother’s house in Arkansas for Thanksgiving during my childhood. We had turkey, cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie. Imagine my surprise when I learned through newspaper articles in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives that Thanksgiving was not always celebrated in the South!

This year, on the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims landing at Plymouth Rock, it’s fitting to share what newspapers tell us about when Thanksgiving spread to the South.

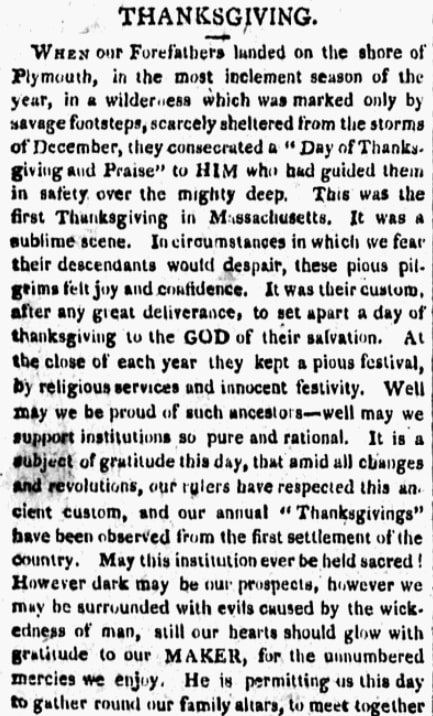

The Pilgrims celebrated their first Thanksgiving in 1621. Massachusetts’ Salem Gazette reflected in 1813 that “Our annual Thanksgivings have been observed from the first settlement of the country. May this institution ever be held sacred!”

When the New England Society of Philadelphia began holding its annual Thanksgiving feast to honor their New England tradition in 1815, they also sought to reinvent the dour image of their Pilgrim forefathers.

In 1817 the Vermont Intelligencer and Bellows’ Falls Advertiser printed a speech that Nathaniel Chauncey gave at the annual New England Society of Philadelphia’s Thanksgiving dinner. In introducing Chauncey’s remarks, the newspaper’s editor wrote:

“Some of the observations it [Chauncey’s speech] contains are particularly adapted to the meridian in which it was delivered, and were intended to counteract certain prejudices against the first settlers of New-England, which are too common in the Southern parts of the Union.”

Thanksgiving became an annual national holiday when President Lincoln issued a proclamation in 1863. Because of the Civil War, it’s no surprise that many in the South initially opposed Thanksgiving. “King Abraham has issued a proclamation appointing the last Thursday in November as a day of thanksgiving and prayer in Yankeedom,” South Carolina’s Charleston Courier derided on October 12.

Georgia’s Augusta Chronicle went further on October 15 by accusing Lincoln of fake news. “The document is on a par with the rest of the productions that have been sent out from Washington. Bombastic in tone, and full of false statements. In a thanksgiving proclamation one would suppose that Lincoln would tell the truth, but he has not.”

How did Northern newspapers respond? In contrast, they put a positive spin on giving thanks. Cleveland’s Plain Dealer was thrilled on November 25 that “the whole North will be eating Thanksgiving dinners and mingling in social glee together, upon that occasion. What a grand spectacle!”

When did Americans in the South unite around Thanksgiving as a national holiday? It took more than 10 years.

Ten years after Lincoln’s proclamation, the Augusta Chronicle wrote in 1873 about how Thanksgiving was different in the North and South.

“In the New England States, Thanksgiving Day is looked forward to with even greater pleasure than Christmas,” it reported, while observing that Northerners “prepare mountains of doughnuts and pumpkin pies for the occasion, the fatted goose is killed, and everybody is full of the event.”

In the South, the paper reported, Thanksgiving was still merely a day off – a time to close the banks, not to feast.

“In the Middle and Southern States less attention is paid to the day, and beyond its observance as a legal holiday and the services at the churches, where thanks are returned to a Gracious Providence for the blessings of the past year, there is no demonstration.”

Though Southerners still weren’t feasting on pumpkin pie, they were beginning to give thanks, which was an improvement.

Giving thanks and counting their blessings eventually brought Southerners around to feasting and fully embracing Thanksgiving. The proof wasn’t in the pudding or football but in the turkey.

In 1883, the Abbeville Press and Banner in South Carolina published this Thanksgiving ditty:

Clearly this clipping, among other articles of the time, show that feasting had become part of Thanksgiving Day in the South.

Twenty years after Lincoln declared the last Thursday in November as the annual day of Thanksgiving, Southerners and Northerners alike were all feasting. New England’s Thanksgiving had come of age everywhere.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Related Articles: