Along with its many dead and wounded, the U.S. Civil War caused the pain characteristic of all civil wars, when a country turns upon itself and brother fights brother, friendships are torn apart, and neighbors become enemies.

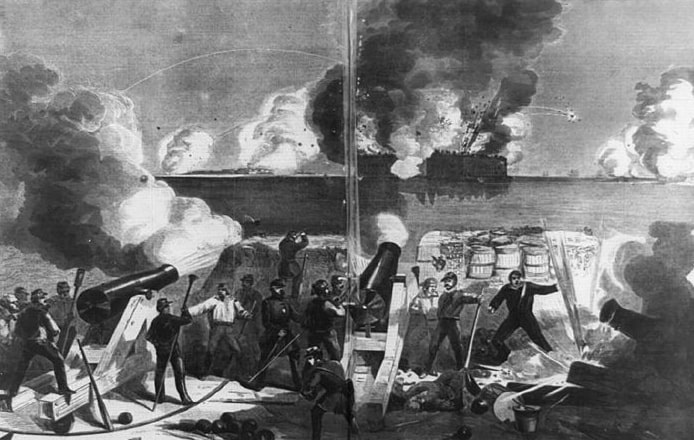

These painful divisions occurred throughout the Civil War, right from its opening battle: the attack on Fort Sumter the morning of 12 April 1861. The Union commander of the fort’s garrison, Major Anderson, had been the artillery instructor at West Point for the commander of the Confederate forces, General Beauregard, and the two men were close friends.

Less prominent friendships were also affected by the Fort Sumter attack. Two Scottish friends were living in Charleston in the spring of 1861 as the attack drew near; one living in the city itself, the other part of the Yankee garrison inside the fort.

The Charleston resident wrote:

“Friend C., I would like you to come over and join us. The North is not worth one cent, starvation staring them in the face. I am down on the Yankees. They are two-faced.”

To which his friend in the fort replied:

“True, I have no part or lot with either North or South… Circumstances have made me the servant of the United States, and my country tells me in her history to do my duty as her sons have done before me in many a country not their own. I would not be Scotch if I didn’t, and in the coming ‘melee,’ should I happen to get rubbed out, I will try and die as easy as any damned rascal like myself deserves.”

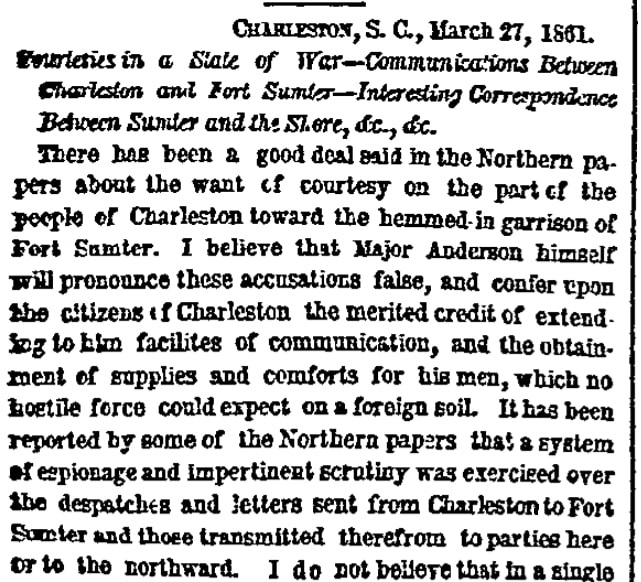

Here is a transcription of this article:

Courtesies in a State of War – Communications between Charleston and Fort Sumter – Interesting Correspondence between Sumter and the Shore, &c., &c.

Charleston, S.C., March 27, 1861.

There has been a good deal said in the Northern papers about the want of courtesy on the part of the people of Charleston toward the hemmed-in garrison of Fort Sumter. I believe that Major Anderson himself will pronounce these accusations false, and confer upon the citizens of Charleston the merited credit of extending to him facilities of communication, and the obtainment of supplies and comfort for his men, which no hostile force could expect on a foreign soil. It has been reported by some of the Northern papers that a system of espionage and impertinent scrutiny was exercised over the despatches and letters sent from Charleston to Fort Sumter and those transmitted therefrom to parties here or to the northward. I do not believe that in a single instance the sanctity of a private seal has been violated in the transmission of any written communication to or from Fort Sumter by the constituted government of the Confederate States or of the State of South Carolina. I have taken some pains to ascertain whether this were true or not, and the further I have investigated the more I am satisfied that my original conclusion was correct. For the sake of illustration, I will enclose to you a couple of letters from a subaltern officer in Fort Sumter, to a friend in Charleston, and his reply, all of which were freely communicated to me by the parties concerned. The following is a copy of the first letter:

Fort Sumter, S.C., March 20, 1861.

Old Fellow – Sebastopol is not taken yet. I’m damned sorry we are going North, although probably it is better than to have a rumpus here. What grieves me most is to leave this post now that we have it in a perfectly defensible condition. All our time and labor lost, and not to have a fight – too bad – too damned bad. Sober times here, I tell you; not a drop to be had. W. said he broke what you sent by him. I don’t believe it. Our grub is nearly gone, and we must go soon. Now to business: On our hurried exit from Moultrie of course, everything was left behind. My discharge for the last five years I would like to recover. I left it, with some other papers, in our old quarters. It is of no use to any one but myself, and if ever you hear of it secure it for me, will you? Let me hear from you before we go, and, if possible, that is, if you could procure it without much trouble, send me two or three skeins of black and one of red sewing silk, to patch up a uniform for me, for I swear I’m in tatters. This will read somewhat in the begging line, but if you had been three months cooped up as we have been, you might adopt the same strain.

How is my worthy friend Mr. D. McK., the would-be Knight of the Silver Whistle? Tell him I dispute his right to the title, and only wish that he and the material were here; am confident I could whip him. That’s enough, or, as the fancy say, “nuff sed.”

In reply to this, the following letter was sent by the gentleman to whom it was addressed:

Charleston, South Carolina, Confederate States of America, March 23, 1861.

Dear Friend – I was more than pleased to receive your note of the 20th inst., and learn that the papers you left behind are in good hands, in the officers of the army of South Carolina, who took possession after you left. Enclosed you will find the silk you wanted, having received it from your townsman, Mr. S___, as a present. I am astonished at your officers, some of them being Southern men. (Why don’t they resign?)

I was in conversation with Lieutenant C___; he has resigned and joined us. He looks well. He left Texas some three weeks ago.

You say you are sorry to leave without a fight. I think you should be damned glad if we allow you to go away without it. You have no idea how many infernal machines we have now ready for an attack; that is to say, if reinforcements should attempt to enter the harbor, we would be in possession of Fort Sumter in a few hours. If ever reinforcements are sent, woe to Sumter and all within its walls. You have no idea of the feeling that exists here; we are fighting for our homes.

I have heard the ladies say that they would help in carrying ammunition to the men. So you can judge the power that the fair sex have in times of peace, and at present it acts doubly so. I speak for myself.

Friend C., I would like you to come over and join us. The North is not worth one cent, starvation staring them in the face. I am down on the Yankees. They are two-faced. I volunteered to come in one of the infernal machines to have a crack at old Tom for fun. I think the old boy would get awfully skinned if we should attack you, but at present you may feel safe. We are honorable, and will give you notice. I shall be happy to hear from you at any time, and shall be happy to do anything for you in my power.

Your friend,

W. Mc.

In response to this the following reply was received from the bonnie chiel’, who takes things as coolly as if he were with his lassie in fair Edinboro’ town. He talks Sumter and Scotch courage as if they were mingled in one haggis:

Fort Sumter, S.C., Sunday, March 24 – 1 p.m.

My Dear Sir – Yours dated yesterday is received. I am exceedingly obliged to you and my friend S., of bonny “Bon Accord,” for the means of “making me look decent.” Truly I was rather seedy to make my reappearance in society.

You seem to have mistaken the import of my last note, or I must have expressed myself equivocally. I do not, nor never did, entertain a hope that a struggle between three score and ten men and as many thousand, could result by any possible means in favor of the former. There is honor, in my opinion, in being beaten under the circumstances; at least I can see no dishonor in it. I would not give a fig for a soldier who can fight only on the side that’s sure to win; and the soldier who is not ready to do his duty under any circumstances, is not worthy of the name. What galls me more than anything else is the headlong action of the people of the North, who, with genuine American enthusiasm, before anything has occurred to deserve more than a passing notice, indulged in such a flood of bombast about our devoted little garrison as to make us actually ashamed of ourselves, and in a great many cases eager to do something like what their imaginations depicted as already performed. It will come to war sooner or later, and I for one would as soon do my share of it behind the walls of Sumter as anywhere else.

True, I have no part or lot with either North or South. My nationality is like the laws of the Medes and Persians. Circumstances have made me the servant of the United States, and my country tells me in her history to do my duty as her sons have done before me in many a country not their own. I would not be Scotch if I didn’t, and in the coming “melee,” should I happen to get rubbed out, I will try and die as easy as any damned rascal like myself deserves. Avast with your three or four hours, tell that to the marines. When we are gone (to hell or Halifax), slip over and take a look at Sumter; I will leave it to yourself; I can say nothing, but should this post be peaceably evacuated, come and look at it. Should there ever be a fight here and we likely to lose, you never will see it, nor any one else.

I am greatly obliged to you for the trouble you have taken in ascertaining the whereabouts of my discharge papers. You need not put yourself to any unnecessary trouble about them, as I am satisfied to know they are not lost. I hope to get a squint at you before I leave, but as yet I cannot imagine how we will leave. How is J.R., soldiering or anything? Ha, ha; that’s good. My respects to all my acquaintances, and believe me truly yours, and in a terrible hurry,

J___ C___

From the character of the above, which is but a sample of the correspondence that has been kept up from the fort to the shore since Major Anderson retired from Moultrie to the only four acres of territory that is not now in the possession of the State of South Carolina, and over which the Palmetto flag floats, until the present time. The Convention now in session proposes to restrict if not entirely abolish the facilities which enable the men in the fort to communicate with their friends on shore. But it is doubtful whether the proposition will be adopted.

Your correspondent should take this, the earliest opportunity, to state that he was not menaced with detention in any shape, except in the way of hospitality, during his late sojourn among the works on Morris Island. Every facility was afforded him to obtain information, and the report that he excited suspicion, and was indebted to the timely interference of General Beauregard for the privilege to leave the island at his pleasure, was simply a ruse to allow him to enjoy the good fellowship of the Morris Islanders a little longer than his time would permit.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in the Civil War? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

Related Articles: