Introduction: Gena Philibert-Ortega is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.” In this guest blog post, Gena explores one of her many interests: the connection of food and cooking to family history, revealing how much oysters were part of our ancestors’ diets.

What did your ancestors eat? Is this something you ever ponder? As family historians, the actual everyday activities of our ancestors can help to bring the dates and places we research to life.

In some cases the food our ancestors ate is quite different from what we are accustomed to today. With the lack of refrigeration and transportation, it’s no surprise that there were regional differences in cuisine. Considering the limited ability to transport and preserve ingredients, the variety of what was available to harvest locally, and the food preferences of local ethnic/immigrant populations, it is not surprising that the food that was served in various areas could be extremely different. A specialty enjoyed by those living in one region of the United States was all but unknown in another. While to some extent this is still true of modern cuisine today, as you can travel to different regions of the United States and taste local favorites not served where you live, these food differences are not as dramatic as they were 100 years ago.

So what were some food commonalities? Well there were many American foods that were feasted upon across the regions. One such food that was enjoyed by almost all Americans in the nineteenth century was oysters. Today oysters, depending on where you live, are usually a delicacy because of the price they command. It would also not be unusual to find people who have never even tried an oyster, raw or cooked. In the nineteenth century oysters were everyday food items that were inexpensive and plentiful. They were the food of the common person.

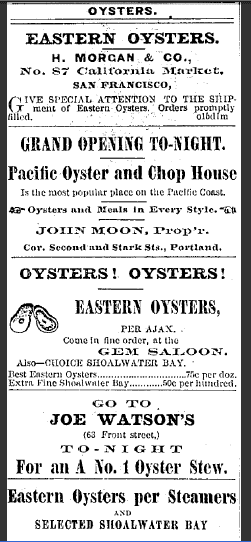

Newspaper advertisements hint at the massive amounts of oysters available to our ancestors. Consider this 1874 newspaper advertisement from the Oregonian which lists several places to eat and obtain oysters.

Street vendors, oyster houses, saloons, restaurants and home cooks prepared oysters in various, often creative ways. Oysters were served in every way imaginable including ways we are familiar with today like raw and fried. Interesting ways to serve oysters could be found in the era’s cookbooks including pickled oysters, oyster ketchup and one recipe that called for oysters to be served with shortcake.[i]

Consider this newspaper article which provides 11 ways to cook oysters that “if adhered to will bring cheer to the family board.” Note that this article was printed in a Kentucky newspaper—not exactly known today for its seafood. Yet this historical 1913 article tells “how best to serve the succulent bivalve [oysters], perhaps the most universally popular dish of the American table.”

There were also “mock oyster” recipes for those who were unable to obtain oysters. These oyster recipes substituted different ingredients for oysters including corn, mashed potatoes, tomatoes, and eggplant. Women could cook dishes such as “Mock Oyster Soup,” “Mock Oyster Sauce,” “Mock Oyster Stew” and just plain “Mock Oysters.” While the appearance of a “mock” recipe in a cookbook might connote that the item was difficult to obtain or expensive, this was not necessarily so in the case of the oyster.

As oyster beds became contaminated and overfished in the early 1900s, oysters began to cease being eaten as an everyday food and became more of a delicacy. No longer was the oyster part of America’s everyday diet.

To learn more about America’s love affair with oysters see the history The Big Oyster. History on the Half Shell by Mark Kurlansky.

[i] Stavely, Keith W. F., and Kathleen Fitzgerald. America’s Founding Food. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2004, pg. 108. Viewed on Google Books 1 July 2012.