Introduction: In this article, Gena Philibert-Ortega writes about how difficult it can be finding information about an ancestor who was committed to an asylum (i.e., state hospital)—and how using old newspapers can help. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

When I look at the latter years of one set of my paternal 2nd great-grandparents, I see a similarity. They both had divorced and later remarried, and their latter years were marked by the same outcome: they spent their final years in a state hospital, called an “asylum” in those days.

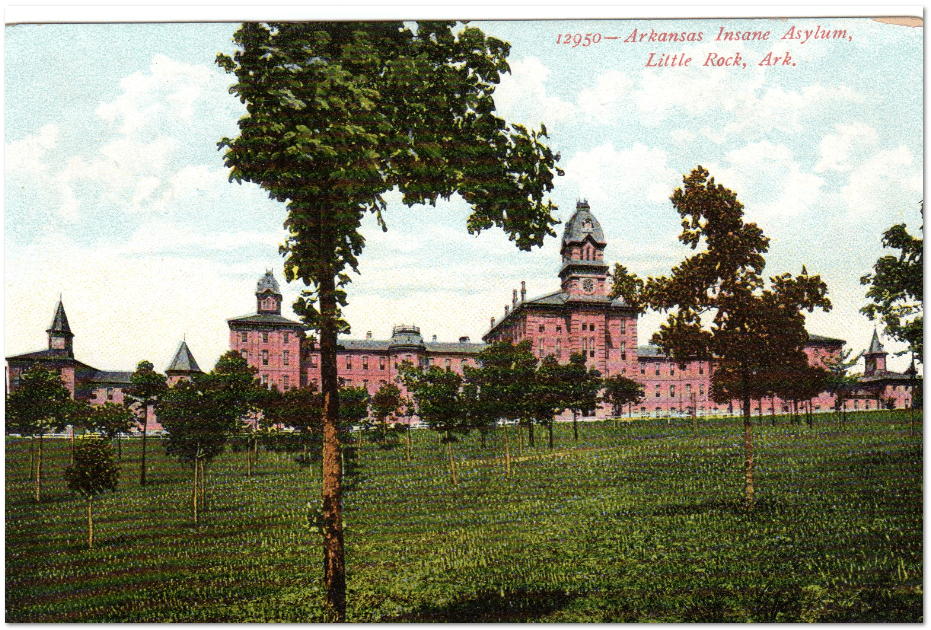

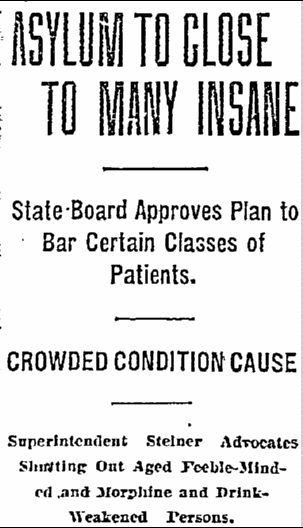

Asylums served the needs of more than just mentally disabled people: they also served as a place for the elderly who needed care. In an American era before rest homes and specialized elder care, asylums were available to care for elderly persons whose family could not—or would not—care for them. While we often associate the words “insane asylum” with mental illness, historically many different types of people were locked up in asylums who were anything but mentally ill. For example, besides the elderly, women who didn’t conform to society’s ideas of what a woman should be were sometimes locked up at the whim of their husbands or other male family members.

Researching your ancestor who was committed to an asylum can be difficult due to the lack of sources, as well as privacy law restrictions. This is where social history sources can help your family history research.

In the case of my paternal 2nd great-grandmother, Malinda Randall Montgomery Bean, she spent less than a year in the Oregon State Hospital located in Salem, Oregon, in the 1940s. (To learn more about the Oregon State Hospital, visit their museum online at Oregon State Hospital Museum of Mental Health.)

I knew a little bit about Malinda from interviewing family members but I wanted to know more. I was especially interested in her life between the years after her second husband died in 1935 and her own passing nine years later. I knew from family sources that she suffered dementia in her later years, which helped explain why she lived her last months in the state hospital.

To find out more about Malinda’s life I took a genealogy trip to Oregon, researched at the Oregon State Archives, visited the grounds of the hospital (still in existence), and found her burial place. Because I was limited in what I could learn about my ancestor’s life during her time at the state hospital, I researched old newspapers to understand the life of asylum patients during the early 1900s.

One gets a sense of the normalcy of sending the elderly to live out their final years at a state facility from this 1911 newspaper article, which is about the Oregon State Hospital asking families to not send their elderly to the hospital due to concerns about overcrowding, and instead take care of them at home or have the county care for them.

Reading a later newspaper article from 1940 lamenting the crowding of the facility gives me a sense of what my great-great-grandmother’s living conditions must have been like at the end of her life. One danger from the overcrowding is mentioned in the news article: fire. The old newspaper article states “The main building, built in 1883, is tinder dry, and its floors are soaked with the oil of many cleanings.” It goes on to say that the elderly are housed on the first floor just in case they need to escape during such a tragedy.

Besides problems with overcrowding in the asylums, there were other dangers for those living in institutionalized care. For example: right before my ancestor was a resident at the Oregon State Hospital, some cooks from the facility were charged in the deaths of 47 inmates. They served residents roach poison mixed in their food!

Malinda “Lennie” Bean died on 19 March 1944 of bronchopneumonia and “senility” at the age of 79 years. Her family paid for her final arrangements and her subsequent burial in a nearby cemetery. According to her death certificate she had lived in the Oregon State Hospital for 9 months and 29 days.

Although doing genealogy research on an ancestor who spent time in an asylum can be difficult, don’t forget the power of incorporating social history—found in historical newspaper articles— to help you better understand their lives and the times in which they lived.