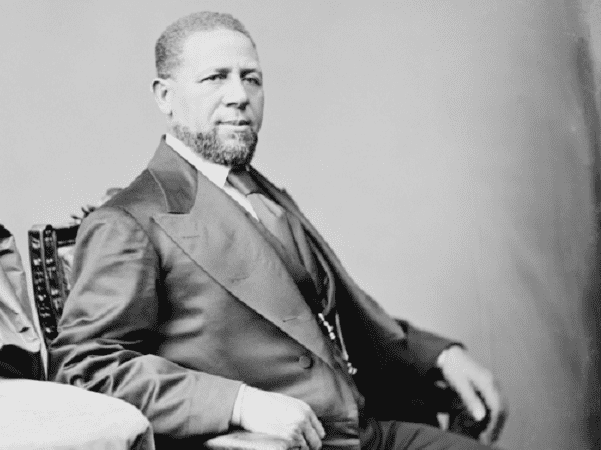

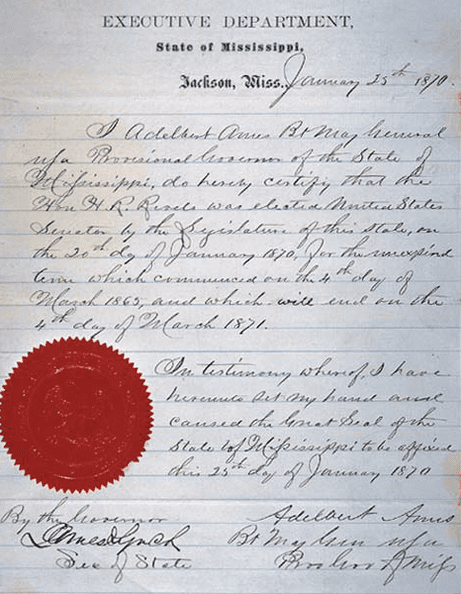

February is Black History Month in the United States, and on this day an important event happened in U.S. and African American history. One of the clearest signs that Reconstruction was changing the face of America came when Hiram Rhodes Revels was sworn-in as the new senator from Mississippi on 25 February 1870, becoming the first African American member of the U.S. Congress.

Although his election received the strong support of Senate Republicans and members of the liberal press, conservative Southern Democrats tried to block Revels by referencing the notorious Dred Scott Decision of the U.S. Supreme Court. Racist newspapers denounced his selection, one referring to “the Senatorial Simian” and another using the frontpage headline: “The Mississippi Gorilla Admitted to the Senate.”

The center of the controversy, a son of a white mother and mixed-race father, was a 42-year-old minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church who had been elected to the Mississippi State Senate in 1869. That body, by a vote of 81 to 15, elected to send him to the U.S. Senate (senators were not elected by popular vote at that time) to fill one of the two seats left vacant when Mississippi’s two senators resigned in 1861 because of their state’s secession from the Union. (One of those two resigning Mississippi senators had been Jefferson Davis, who became the president of the Confederate States of America – an irony not lost on many political observers.)

Opponents to Revels relied on the 1857 Dred Scott Decision, which ruled that Africans brought into the United States – as well as their descendants – had no rights under the U.S. Constitution and could never be U.S. citizens. His opponents insisted that since the Fourteenth Amendment (granting citizenship to ex-slaves and their descendants) had only been ratified in 1868, Revels could only have been a U.S. citizen for two years, not the requisite nine required for eligibility into the Senate.

His supporters derided the racism inherent in the Dred Scott Decision, and pointed out that it only applied to persons of pure African blood. Since Revels was of mixed race, they argued, the vile Dred Scott logic did not apply to him anyway – and most of the Senate agreed. Senators voted 48 to 8 to accept his selection by the Mississippi State Senate, and his term began on 25 February 1870, lasting little more than one year. Revels resigned on 3 March 1871, two months before his term was to have expired, to become the first president of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University) in Mississippi.

The Senate debated whether to admit Revels. In a small post, the New York Herald made this snide comment.

Here is a transcripton of this article:

REVELS.—Both parties in the Senate are disposed to freeze out the colored Senator from Mississippi. He was discussed a little yeaterday without being admitted. He begins to look black about it.

In the same issue, the New York Herald reported on the actual Senate debate. Far from “both parties” being “disposed to freeze out” Revels, as the above article claimed, the actual debate shows that Republican senators favored his admittance to the Senate, with the Democrats opposed.

Here is a transcription of this article:

THE CASE OF THE MISSISSIPPI SENATOR.

The Mississippi subject was then taken up, the question being upon the motion of Mr. Stockton to refer the credentials of Mr. Revels to the Judiciary Committee.

Mr. SAULSBURY, [(Dem.) of Del.], discussed the question of the alleged election and the evidence of it, and said he supported the proposed reference upon the higher and broader ground which was entertained by his political associates in the Senate, that under the Constitution he (Revels) was not eligible to a seat in the Senate on the ground of a want of citizenship. He denied that any claim to eligibility could be established by the civil rights bill or the Fourteenth Constitutional Amendment, because the Constitution required nine years previous citizenship of applicants for seats in the Senate, and the requisite nine years since the enactment of the legislation referred to had not elapsed. But it was claimed that Mr. Revels was a citizen prior to this legislation. The answer to that was that the Dred Scott decision was, at the time of its delivery, the only authoritative exposition of the Constitution on the point that a negro or mulatto was not such a citizen of the United States as was contemplated at the time of the adoption of the Constitution. The principle involved in this decision, he said, had been endorsed by all the radical legislation, because the civil rights bill and the Fourteenth Amendment were based upon the conviction of Congress that at the time of the Dred Scott decision free negroes and free mulattoes were not citizens of the United States. He then went on to argue that it was not competent for any one State to make a citizen of the United States. Consequently if Mr. Revels had ever voted in Ohio, of which there was no evidence, it was in violation of the Constitution of the United States. In conclusion he remarked he had but little hope for the future of his country. He would avert, if possible, this threatened calamity. He would preserve to our white posterity this heritage bequeathed by our honored and noble ancestry to their white descendants. He recognized, however, that his own efforts would not avail, and, therefore, in resuming his seat he would utter his solemn protest against this proceeding in behalf of a revolutionized country.

Mr. DRAKE (Rep.) of Mo., during the remarks of Mr. Saulsbury, made the statement that Mr. Revels was neither a negro nor a mulatto, but an octoroon, and that he made the statement out of compassion for the mental sufferings of his friend (Mr. Saulsbury) upon the probability of being compelled to associate in the Senate with a jet black negro.

…Mr. HOWARD, (Rep.) of Mich., believed the proof of Mr. Revels’ election to be conclusive, and that the only issue now was upon the acceptance or rejection of him as a member on account of the color of his skin. It was urged that he (Mr. Revels) was of African descent, and therefore had not been a citizen of the United States for nine years. It was not denied that he was a native born inhabitant of the United States, nor was it pretended he was a slave. He (Mr. Howard) maintained that every person born in the United States and not been a slave was a citizen; that nativity imparted citizenship in all countries. He would carry this doctrine so far as to assert that even a black man born a slave was to be held to be a citizen from his birth. Such a one had always owed allegiance to the United States, and allegiance and citizenship were co-relative terms. The Dred Scott decision, in his opinion, was a partisan decision, the purpose of which was to establish, by judicial decision, for all time to come, the legality, the rightfulness and even the piety of slavery, and it had sunk, if not into oblivion, then, into eternal derision and contempt. He saw in this election of a colored man to the seat formerly filled by Jeff. Davis that which he believed would gladden the heart of every lover of freedom.

Mr. WILLIAMS, (Rep.) of Oregon, remarked that Chief Justice Taney expressly limited the Dred Scott decision to those with pure African blood in their veins and whose ancestors had been sold as slaves; but was there any evidence that the ancestors of Mr. Revels were included in this category? On the contrary, it had appeared in the discussion that Revels was a man with a large proportion of white blood, and it followed necessarily that some of his ancestors were not slaves. Upon the whole, in view of all the authorities, legal and otherwise, Revels had always been a citizen of the United States.

Mr. CAMERON, (Rep.) of Pa., narrated the particulars of an interview between himself and Jefferson Davis just prior to the war and before the latter had left the Senate, during which he declared to Davis his own conviction that slavery would have ceased from the moment the first gun was fired upon the flag of the country, and that his (Mr. Davis’) seat would some day, in the justice of God, be occupied by a negro. Mr. Cameron said he had lived to see his assertion verified and he now wished to remind the Senate how much this colored race had served us in the war, and he was compelled to say this in view of the attempt of the Senator from Oregon (Mr. Williams) to argue that this man (Mr. Revels) had more white than black blood in his veins. A consideration of that kind was unworthy of any Senator in view of the great services of the colored soldier, and he (Mr. Cameron) believed the tide of war would have gone against us had it not been for the two hundred thousand negroes who came to the rescue.

Without action upon the question the Senate, at half-past four o’clock, adjourned.

Tired of the arguments made against admitting Revels – arguments such as that made in a speech by Senator Davis, who reasoned that since white senators don’t marry black women or take black women to balls, they shouldn’t have to serve with a black man in the Senate – the New-York Daily Tribune derided this “futile persistence in prejudice.”

Here is a transcription of this article:

Mr. Senator Davis’s speech on the admission of Mr. Revels to the Senate was simply silly. Do Senators offer to marry black women? No! Do Senators wait upon a colored Dinah to balls? No! Ergo, Mr. Revels must not be allowed to take the seat to which he was regularly elected! What surprises us is, that men with a scintilla of common sense do not see how childish are these belated objections to that which has become an established part of the Constitutional law of the land. As nothing is to be gained by this futile persistence in prejudice, we are inclined charitably to ascribe it to a moral and mental infirmity for which men like Mr. Davis are not to be held responsible.

One Ohio newspaper was certainly not pleased by the Revels selection, and took a swipe at him and the Senate in the following editorial.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Negro Senator from Mississippi.

A negro, who rejoices in the name of HIRAM R. REVELS, is about to take his place in that once exalted body known as the Senate of the United States. He goes there upon a certificate of election from the Legislature, signed by General AMPS, the United States Military Commandant in Mississippi, who is himself REVELS’ colleague, elected in the same manner to the Senate. The principal, of course, certified to the choice of the accomplice in the fraud. There is a little incident connected with this honorable Senator which is worthy of notice. On or about the last of August, 1867, this colored gentleman was a citizen of the State of Kansas. He instituted a suit or criminal prosecution against one JOHN H. MORRIS for charging him (REVELS) with embezzling the funds of his (REVELS’) church and with falsehood and hypocrisy. The defendant (MORRIS) justified and claimed the truth of his allegation. The jury took the matter under advisement, and returned the following verdict:

“The defendant (MORRIS) took the ground that the alleged libel was true, and proved to our satisfaction that the said HIRAM R. REVELS had embezzled certain funds belonging to his church, and has been guilty of falsehood, and had unnecessarily forced a quarrel on the said MORRIS thus compelling him to act in vindication of his own character.

“In short, we found that the alleged libel was true, and that it was published for good motives and justifiable ends, all of which it was necessary to prove to secure an acquittal in a suit for libel.”

E. M. RANKIN, Foreman;

JAMES CURRAN,

ABEL ARMSTRONG,

A. L. RUSHMORE,

H. MARKSON,

J. B. FLUNO.

Mr. RANKIN is a wealthy and prominent citizen of Leavenworth; Mr. MARKSON is a Deputy Collector of Internal Revenue; and Mr. FLUNO is a hotelkeeper in the principal city of Kansas. The whole jury is eminently respectable, and no one can doubt the justice of their verdict, as it was under oath upon presentation of the evidence. Such is the man – who two years ago had never seen Mississippi – the majority of the United States Senate receive into their fellowship as a worthy and estimable colleague. Well, perhaps, under the circumstances, he may be deserving of that appellation.

Another, even more appalling, editorial was published by the Chicago Republican, then reprinted by the Oregonian. It seems a New York paper, the World, sent a correspondent to interview Revels – which infuriated the editorial writer at the Chicago Republican, who called Revels “the Senatorial Simian” and clearly didn’t think any respectable newspaper should pay attention to Revels at all.

Here is a transcription of this article:

The Collapse of Democracy.

(From the Chicago Republican.)

“Whyfore is this thus?” Can such things be? Is this article in the New York World a forgery, or an optical illusion? Is it possible that the Washington representative of that distinguished Caucasian journal has actually besought an interview with the negro who has been sent to the United States Senate from Mississippi? It would seem so, if we can trust our eyes; and it would further seem that the correspondent became bewildered by the fascinating presence – magnetized into a renunciation of the great leading “principles” of Democracy.

He actually visited the Senatorial Simian at the residence of “the colored President of the Freedman’s bank,” where, although a “social party” was in progress, the correspondent failed to detect any overpoweringly obnoxious odor. He stood it. His handkerchief did not envelope the facial promontory wherein dwell the alert olfactories.

He took an inventory of the features of the sable successor of Jeff. Davis, and found that he had “a decidedly African, but pleasant physiognomy.” He was tickled almost to death when “the Senator” condescended to sit for five minutes and answered his dismal questions; and he asked him almost everything except whether the hollow of his foot made a hole in the ground.

He observed his curly hair, and saw in it [no] disqualification; he noticed that he was pretty black, and remembered that it was a complexion to be euphemistically referred to as the rich olive of the South; he made a note of the conspicuous nose, and declared that he looked “as benignant and philosophical as one could wish”; he took a sketch of the Senegambian skull and pulpy lips, and discerned therein a sign that “he may flame out as a raging orator on the Senate floor.” The writer doubtless adores the Coxian style; but we have enough of that sort of “raging” orators, and we pray that Revels may “take any shape but that.”

By this time, Jenkins is thoroughly demoralized. He has repudiated the Dred Scott decision; and Taney and Buchanan are among the unremembered dead. At this point he probably eats an orange and takes a drink. He can’t make the Afrite go back into the bottle again, and he don’t try. He surrenders. And he describes the Senator as he sits there, “with his cheeks cleanly shaven, leaving a closely-cropped beard on his chin, with his face all smiling and his soft brown hand softly stroking your correspondent’s knee.”

Good gracious! Ghost of the sublime Hoang-ti! Has Democracy come to this? Is it possible that the New York World offers its matchless knee to be petted by “the soft brown hand” of a member of that degraded race, whose ancestors, according to Democratic ethnology, a few generations ago, hung by their tails from the limbs of Angolan palms? Let the curtain drop! This is too much.

The historic Senate vote clearing the way for Revels to take his seat was reported by the New York Herald.

Here is a transcription of this article:

WASHINGTON.

The African in Congress at Last.

The Colored Senator from Mississippi Sworn In.

…

Washington, Feb. 25, 1870.

Admission of Senator Revels.

After three days of debate, wherein the negro has been viewed in every aspect except, perhaps, a religious one, Revels, the negro Senator from Mississippi, qualified and took his seat in the Senate today. The Senate galleries have been crowded by persons anxious to witness the novel sight of a veritable negro taking his place in the Senate of the United States alongside of white men. Judging from the anxiety pictured on their countenances and the uneasiness manifested to get a good look at the operation of swearing Revels in, the people in the galleries must have expected something terrible to follow. After the vote had been taken, when the presiding officer called upon Revels to come forward and take the oath, there was a general buzz in the galleries, a rising up and a bending forward, as if the appearance of some monster was expected in the Senate Chamber. Revels, who had been sitting all day on a sofa in the rear of Mr. Sumner’s seat, advanced towards the Clerk’s desk with a modest yet firm step. He was in no way embarrassed, but went about the business of being sworn in as though he had been accustomed to it. Of course he swallowed the iron-clad oath without wincing, and bowed his head quite reverently when the words “so help you God” were rendered. Immediately after qualifying Revels walked to the seat in the rear of Senator Brownlow, which, I am told, he intends to occupy… It was a mercy to the Democrats that Revels did not select a seat on their side of the Chamber. Had he done so the consequences can scarcely be conjectured. Garrett Davis would have been compelled to resign, Saulsbury would have had to go home to Delaware and New Jersey might have been put to the trouble of welcoming home her Stockton. As it is, however, Revels is in, nobody has gone out and the Senate is safe.

Reaction to Revels being sworn in as a U.S. senator was decidedly mixed. The front page of the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer ran this atrocious headline.

Another Cincinnati paper was far more approving.

Here is a transcription of this article:

Yesterday, Mr. REVELS, a colored man, was admitted as United States Senator from the State of Mississippi, in the place last held by JEFFERSON DAVIS. It is little more than nine years since JEFFERSON DAVIS took a formal and somewhat dramatic farewell of the United States Senate, having resigned his place to assume the Presidency of the Southern Confederacy, whose corner stone was proclaimed to be the slavery of the negro race, and whose first principle of social economy that the capitalist should own the laborer. The result of that undertaking is that four millions of human beings who were then slaves, and whom a degraded Supreme Court declared had never been recognized as having any rights that a white man was bound to respect, are now citizens of the United States, endowed with all civil and political rights, and one of that race is now installed in the place which Mr. DAVIS vacated. Verily, the whirligig of time brings strange revenges. African slavery has disappeared, and with it the Confederacy, of which it was to be the corner stone, and the emancipated slaves have become the corner stone in the political reconstruction of the States from the ruin of rebellion.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Articles: