Introduction: In this article – the second in a series of three articles celebrating Thanksgiving – Jane Hampton Cook shows how the tradition of a Thanksgiving feast spread to Pennsylvania. Jane is a presidential historian and author of ten books, including her new book Resilience on Parade: Short Stories of Suffragists & Women’s Battle for the Vote. She is the author of Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. She was the first female White House webmaster (2001-03). Her works can be found at Janecook.com.

How did New England’s Thanksgiving spread to other states? A look at some newspaper articles in GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives shows us how it spread to one state in particular – Pennsylvania – by the time of the Pilgrims’ bicentennial.

In 1815, the Sun of Dover, New Hampshire, reported on a novel event held in Philadelphia by residents who were originally from New England: “a day of public Thanksgiving.”

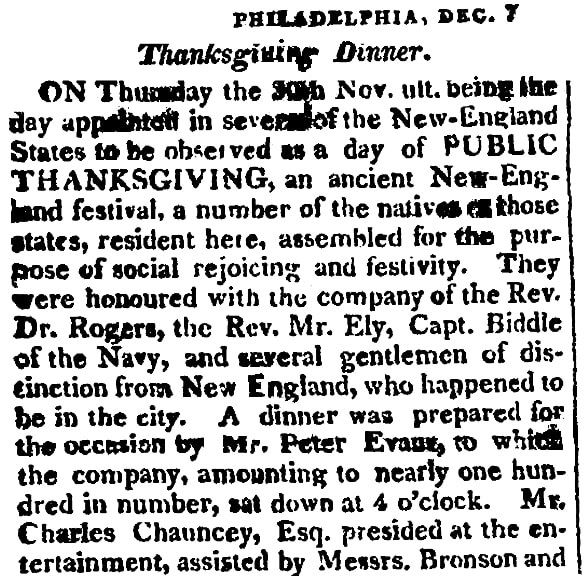

As this article reported:

“On Thursday the 30th Nov. ult. being the day appointed in several of the New-England states to be observed as a day of PUBLIC THANKSGIVING, an ancient New-England festival, a number of the natives of those states, resident here, assembled for the purpose of social rejoicing and festivity.”

Nearly 100 New Englanders who lived in Philadelphia, or were visiting at the time, gathered for this feast and religious service. Their toasts paid homage to the Pilgrims.

They toasted to: “Thanksgiving Day – Venerable for its antiquity among our pious and revered forefathers; and endeared to us by sympathetic associations and fond remembrances.”

They also toasted to “New England the land of our birth” and to “Philadelphia our chosen residence.”

They didn’t want to lose a connection to their heritage, and toasted to: “The steady habits of New England – In removing from the soil, we may not become estranged from the principles of our fathers.”

This Thanksgiving dinner in Philadelphia became an annual tradition. By 1820, the 200th anniversary of the Pilgrims landing at Plymouth Rock, their transplanted Keystone state descendants had a new name: The New England Society of Philadelphia.

This article concluded:

“The company retired at an early hour, highly gratified by the festivities of the evening, which had been devoted to the honor and memory of those ancestors who led the way, and laid the foundation for the establishment of the institutions which secure to us civil and religious liberty.”

For decades the New England Society of Philadelphia held an annual Thanksgiving feast. They published their recipes, which spread the tradition to other locations.

They kept the story of the Pilgrims alive. One address from 1817, delivered by Nathaniel Chauncey, stands out for its poignancy and praise for the Pilgrims.

Chauncey said:

“While at a distance from our first home, we are endeavouring to revive one of its highest pleasures in the observance of a festival which is associated with our early impressions, and our purest, and strongest, and holiest affections, permit me sir, for a few moments, to draw the attention of this social circle, to those who established our feast of love. It has descended to us from our ancestors; it was instituted by the settlers of New-England.”

Chauncey believed that the character of the Pilgrims had been “much traduced – their virtues have been forgotten, and the faults of the age in which they lived, have been imputed to them as their peculiar blemish… Sir, they were men of whom the world was not worthy.”

He said that although the Pilgrims were not insensitive to pain or blind to danger, they were both saints and heroes who had “a grand moral quality” and the energy to press forward.

“But the men of whom I speak, showed the courage of piety,” he said, recalling the spirit of Martin Luther and other historic figures.

“Sir, our ancestors were living martyrs. For the conversion of the heathen, the benefit of posterity, and the honor of their master, they endured exile and danger, and disease and hunger and cold and nakedness and the want of all things.”

He explained that they first endured many problems in England and then later the Netherlands.

“Under the dictates of conscience, they bore fines, and imprisonment, and plunder and the risk of their native country, anxiety and indigence in Holland, and in the New World, the terrors of a desolate wilderness.”

Chauncey reflected on their losses.

“Of the adventurers who landed at Plymouth, half died in the first season, from accumulated hardships. But the survivors would not return [to Europe]. They had taken their lives in their hands and they were prepared for death in its most terrible form.”

He focused on their accomplishment of creating a civil society.

“They hoped to establish a State in which liberty and pure religion should be enjoyed by millions, through a succession of ages. They cherished, and transmitted to posterity, the grand principles of representative government…”

He ended with a toast. “Permit me, sir, to propose: The memory of the Settlers of New-England.”

In introducing Chauncey’s remarks, the newspaper’s editor wrote:

“Some of the observations it [Chauncey’s speech] contains are particularly adapted to the meridian in which it was delivered, and were intended to counteract certain prejudices against the first settlers of New-England, which are too common in the Southern parts of the Union.”

While Pennsylvania was clearly ready to embrace the New England tradition of Thanksgiving, it would take several more decades for this tradition to spread to the South. For that story, see Part III of this series tomorrow.

Explore over 330 years of newspapers and historical records in GenealogyBank. Discover your family story! Start a 7-Day Free Trial

Related Article: