Newspapers have been publishing obituaries for hundreds of years, making it easy for bereaved family and friends to learn the details of the life of the deceased as well as the funeral arrangements.

GenealogyBank has put this information from the past 300 years online, allowing genealogists to find their relatives within a few clicks.

300 years?

That’s a lot of obituaries, resulting in the largest collection online.

Have obituaries really changed much over the course of three centuries?

Yes—of course they have, and so have newspapers.

But the basic rule of thumb has always been true: famous people get long obituaries and not-so-famous people get short ones.

Back in the days before the linotype machine (invented in 1886), the type for printing each day’s newspaper was set by hand. That took time and so, realistically, newspapers were generally only four pages long.

Fewer pages meant that there had to be a balance between the length of the news articles and the number and size of the advertisements. That’s why you see old obituaries that are brief—just one line announcing that some individuals had died—with longer, more detailed obituaries about people the editor thought would be of more general interest.

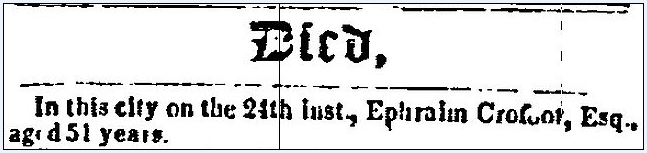

For example, look at the information packed into this brief obituary:

This is a short obituary, but we learn that Ephraim Crofoot died on 24 February 1852 in Middletown, Connecticut. We also learn that he was 51 years old and likely was a lawyer, as indicated by the title “Esq.” [Esquire] following his name.

Now look at these obituary examples:

The opening paragraph has three brief obituaries:

- In this town, of consumption, Dr. Joseph Wheeler, aged 46

- Mrs. Sarah Sturtevant, wife of the late Mr. Cornelius S., aged 88

- An infant child of Mr. John Phelps

Now contrast that last brief obituary for the infant child of John Phelps with the final obituary in this column—also for an infant who had died:

In Fitzwilliam, an infant daughter of Mr. Geo. Damon. Deacon Oliver Damon and wife have lived in Fitzwilliam 42 years, and this [is] the first instance of mortality that has occurred in his family or among his descendants (25 in all) during that time. Printers in Massachusetts are requested to notice this death.

Both were infants that died. Neither obituary gave the name of the child. One obituary was so brief it only gave the name of the father, even though the child died in Keene, New Hampshire, where the newspaper was published.

The other obituary named the father as well, but also provided more details. This infant’s death was “news”—this was the first death in the family of Deacon Oliver Damon in 42 years. This was big and the editor knew his readers would want to know about it. He even inserted the line “Printers in Massachusetts are requested to notice this death,” indicating to other newspaper editors the importance of this obituary in case they wanted to run it in their own newspapers.

The New Hampshire Sentinel published on 28 April 1826 may have only been four pages long, but the editor used his judgment as to how much copy (how many lines) he would give to each story.

Obituaries can be long or short. The size of the obituary was determined by the importance of the person who had died, the story to be told, and the time the newspaper editor and reporters had to research and write about the deceased. As towns grew into cities it became common for the family itself to write the obituary, so that the newspaper would publish more information about their relatives.

Inside the newspaper industry these user-supplied obituaries became known as “Death Notices”—articles written by the family or friends and supplied to newspapers. The articles written by the newspaper staff continued to be called “Obituaries.”

Obituary columns in newspapers have carried all types of headers: Obituaries, Deaths, Died, In Remembrance, Memorials, etc.

For genealogists and the general public, the terms Death Notice and Obituary are synonymous. Most family historians refer to all biographical articles about the recently deceased as obituaries, regardless of who wrote them or how long/short they are.

Over time newspapers came to view these family-supplied articles as paid classified advertisements, and they began charging accordingly. It is customary now for most newspapers to charge by the word count, the inclusion of photographs, and the number of insertions.

Obituaries are critical for genealogists. Long or short, they contain the information and clues we need to document our family tree.

Related Newspaper Obituary Articles:

- Genealogy Podcast 2: Genealogy Research with Obituaries

- 6 Tips for Name Research with Obituaries: Who Are the Survivors?

- 3 Tips to Uncover Hidden Genealogy Clues in Obituaries

[bottom_post_ad]