Introduction: Mary Harrell-Sesniak is a genealogist, author and editor with a strong technology background. In this blog article, Mary shows how obituaries from the California Gold Rush era can tell you more about your ancestors and the difficult times they lived in.

Obituaries, as sad as they are, provide important clues to a person’s life and are an important part of family history research. Beyond just names and dates, obituaries help us learn the stories of our ancestors’ lives.

You may need to read between the lines of an obituary and seek more information from other records. Sometimes, if you are lucky, an extraordinary event may have produced a series of detailed obituaries that are a real boost to genealogy research.

Take for instance, the California Gold Rush (1848-1855). It’s an enlightening and intriguing period to examine, and obituaries from this time period tell some interesting stories.

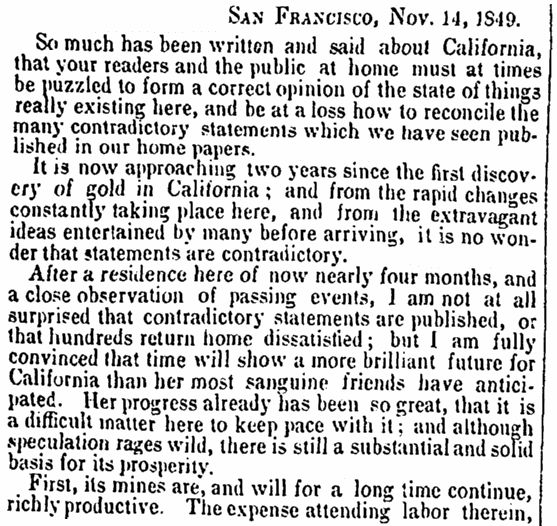

Gold had been discovered on 24 January 1848 at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California. Word of the discovery spread, and by the next year, tens of thousands of prospectors stampeded west, earning the nickname “49ers.” The frenzy of the California Gold rush was spurred mainly by newspaper articles with exuberant comments about the riches to be had. Hardships were noted in some of these articles, but thousands of eager prospectors overlooked these warnings in their desire to strike gold.

It was lines like this that sent the prospectors scrambling westward:

First, its mines are, and will for a long time continue, richly productive.

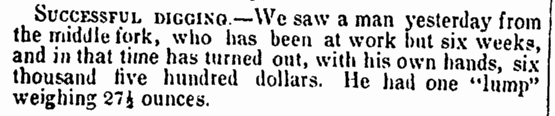

In that same issue is this enticing report:

Don’t Make Assumptions

People flocked to California, but conditions in the goldfields were poor and diseases rampant, so deaths were all too common – but don’t assume everyone in California at that time was hunting for gold. Yes, many died seeking their fortunes – but others succumbed to other causes, as explained in their obituaries.

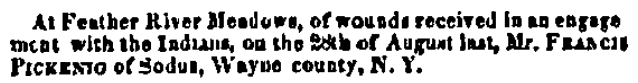

For instance, the Alta California newspaper of San Francisco reported that Francis Pickenig of Sodus, New York, died 28 August 1849 of wounds received in an engagement with the Indians.

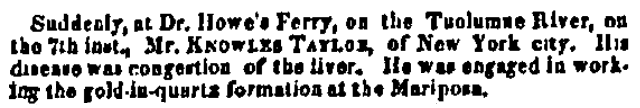

Here’s another example of how a California Gold Rush-era obituary can correct a mistaken assumption. There is a memorial for Knowles Taylor in Union Hill Cemetery in East Hampton, Connecticut (see Findagraves Memorial #47726240). A researcher might assume Taylor, who was from New York City and had family in Connecticut, died in the East Hampton area.

However, his obituary reports that he was prospecting for gold in California when he suddenly died along the Tuolumne River at Dr. Howe’s Ferry.

Genealogy Tip: It is unlikely that the bodies of Gold Rush prospectors were returned East for burial since the practice of embalming wasn’t common until the Civil War period.

Named Locations

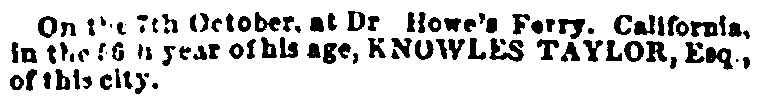

If you’re lucky, the California Gold Rush obituary you’re examining will name the deceased’s home town or county. In the above example with Mr. Knowles Taylor, we learned that he was from New York City. By the end of November 1850, news of his death had reached New York. In this New York City obituary, we now learn that Taylor was an “Esquire” (probably a lawyer) and he died at the age of 56.

Genealogy Tip: Always examine an obituary for named locations.

Timing of Reports

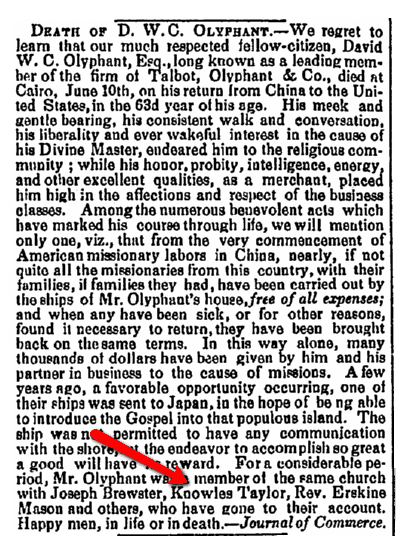

Whenever a person had relocated or died out of town, it’s possible that mention of their death might appear in a newspaper long after the actual date of death. For example, D. W. C. Olyphant’s 1851 obituary noted that he belonged to the same church as Knowles Taylor and others “who had gone to their account.”

Home Town and Widely-Read Newspaper Reports

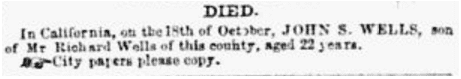

As news of prospectors’ deaths reached their home towns in growing numbers, many local newspapers began increasing their coverage of these California deaths. Many such deaths, such as the notice for John S. Wells of 3 January 1850, were reported in home town papers – St. Louis, in this case.

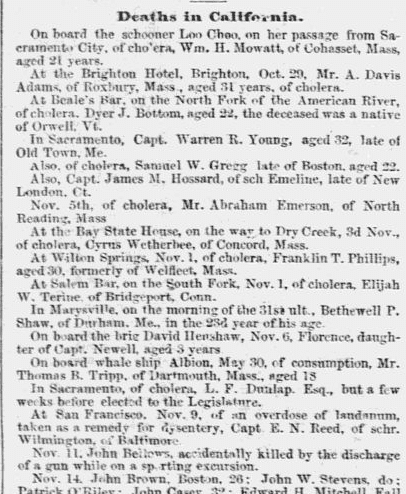

Some widely-read newspapers published regular columns reporting deaths in California. One popular paper was the Emancipator and Republican of Boston, which ran lists of the California deaths. Most mentions in these types of columns were brief, but publishers generally reported where the deceased had resided prior to going west. For example, note the locations mentioned in this notice from 26 December 1850 in Connecticut, Maine, Maryland and Massachusetts.

Cause of Death

Some death notices reported the cause of death. Many of the deaths in the above list were due to cholera, although Mr. Thomas R. Tripp of Dartmouth, Massachusetts, died of consumption and Capt. E. N. Reed of Baltimore, Maryland, died of dysentery. (He tried to cure his dysentery with laudanum but overdosed from this opium and morphine remedy.)

Occupations

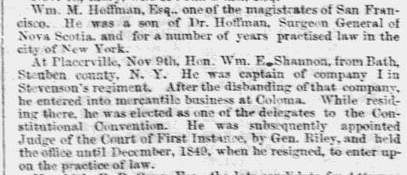

Some death notices also reported the deceased’s occupation. In the following example, William M. Hoffman, Esquire, was “one of the magistrates” of San Francisco and had “practiced law in the city of New York.” He was a son of Dr. Hoffman, the surgeon general of Nova Scotia.

Also, we are told that William E. Shannon from Bath, New York, had been “captain of company I in Stevenson’s regiment.” After disbanding, he went into the mercantile business and became an elected delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

Unrequited Dreams

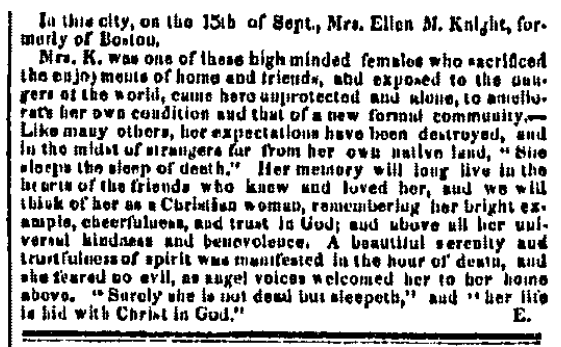

Not everyone who died with unrequited dreams in California during the Gold Rush was male.

The Alta California featured this piece on Mrs. Ellen M. Knight of Boston who died in San Francisco on 15 September 1850:

Mrs. K. was one of those high minded females who sacrificed the enjoyments of home and friends, and exposed to the dangers of the world, came here unprotected and alone… Like many others, her expectations have been destroyed, and in the midst of strangers far from her own native land, “She sleeps the sleep of death.”

Let us know about your California Gold Rush ancestors. Did you find their obituaries in old newspapers? Was there a clue in the death notice that led you to more information? Please tell us about them in the comments section.

Note: FamilySearch International (FamilySearch.org) and GenealogyBank are partnering to make over a billion records from recent and historical obituaries searchable online. The tremendous undertaking will make a billion records from over 100 million U.S. newspaper obituaries readily searchable online. The newspapers are from all 50 states and cover the period 1730 to the present. Find out more at: https://www.genealogybank.com/family-search/

Related Obituary Articles:

- Massive Online U.S. Obituaries Project Will Make It Easier to Find Your Ancestors

- Researching Recent Obituaries to Extend My Family Tree

- Peculiar, Unusual, and Stranger-than-Fiction Obituaries

- Pearls of Life Wisdom from Pink Mullaney’s Obituary

- Truly Personal Obituaries from the Recent Obituary Archives

Thanks for posting this. I found it looking for information on Knowles Taylor, one of your subjects. He was a very successful businessman in New York, and active in supporting religious organizations. Just why he went to the gold fields in his mid-50s is unclear, but there are some indications his fortunes had waned a bit. But the same week he died a New York bank published a list of its liabilities, which included over $250,000 it owed him.

I think the characterization that he was “prospecting” is a bit wide of the mark. The Mariposa Mine was a serious enterprise by 1850, and extracting gold from quartz was a capital-intensive operation. The 1850 census shows him as a clerk, living with a group of men who included miners but also the superintendent. I think more likely he was a manager, perhaps an investor in the mine.