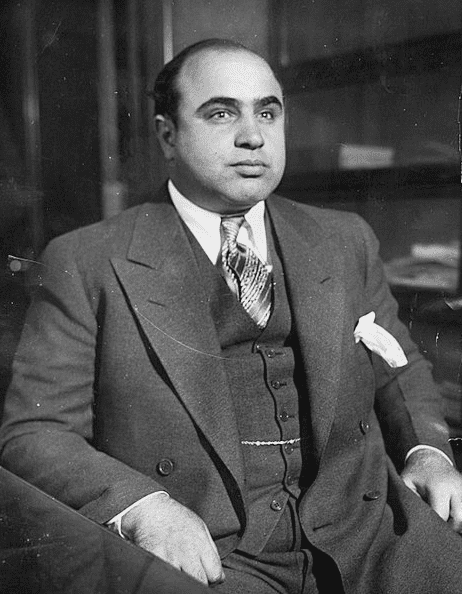

Much of the gangster stereotype in American pop culture stems from the real-life misadventures of Al “Scarface” Capone, an Italian American kid from Brooklyn who became the head of the most notorious gang in violent, prohibition-era Chicago. For six years, from 1925 until 1931, Capone flaunted his wealth and controlled politicians and law enforcement officers while ruthlessly gunning down rival gang members. He lived the life of a king, his extravagant lifestyle fueled by hundreds of millions of dollars gained from such illegal activities as bootlegging, gambling and prostitution.

The government knew of his bootlegging operations, but could not nail him under the Volstead Act. This law, passed on 28 October 1919, defined “intoxicating liquors” to reinforce the Eighteenth Amendment, making Prohibition the law of the land. However well intentioned, Prohibition turned out to be a disaster for the U.S. as organized crime flourished, taking over the now-illegal business of manufacturing, transporting and selling liquor. Many criminal gangs benefited from Prohibition, but nobody flourished more than Capone and his “Outfit” gang in Chicago.

What finally brought Capone down was a tactic he never saw coming: he was indicted and convicted in 1931 for income tax evasion on the relatively paltry sum of $215,000, and sentenced to 11 years in federal prison. He began serving his time in the Atlanta penitentiary on 5 May 1932; in August of 1934 Capone was transferred to gloomy, escape-proof Alcatraz to serve out the rest of his sentence.

It was during his time in Alcatraz that a vestige of Capone’s lawless days caught up with him. Back when the police were afraid to touch him, Capone’s gang operated speakeasies, casinos and clubs all over Chicago. One of Capone’s rules was that any woman who wanted to work as a prostitute in his clubs had to first submit to a personal “interview” with the boss himself. He contracted syphilis, and the doctors at Alcatraz noted Capone had become unbalanced: he was suffering from neurosyphilis, and his mental deterioration was irreversible. Capone spent 1938, his last year at Alcatraz, in the prison hospital. He was transferred to an institution on Terminal Island in California on 6 January 1939, and paroled on November 16.

Capone was only 40 years old, but he was through; he no longer had the mental capacity to operate a large organized crime ring. He spent some time in a hospital in Baltimore, then retired to a home he kept on Palm Island, Florida. He died there on 25 January 1947, from a heart attack, eight days after turning 48.

The following two newspaper articles describe Capone’s mental condition and his stay in a Baltimore hospital after he was paroled.

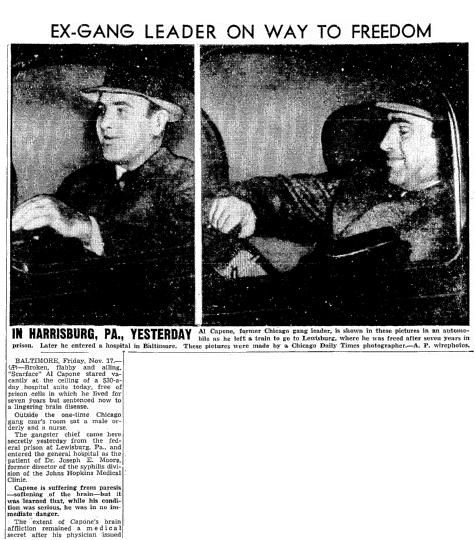

Here is a transcription of this article:

EX-GANG LEADER ON WAY TO FREEDOM

BALTIMORE, Friday, Nov. 17. – (AP) – Broken, flabby and ailing, “Scarface” Al Capone stared vacantly at the ceiling of a $30-a-day hospital suite today, free of prison cells in which he lived for seven years but sentenced now to a lingering brain disease.

Outside the one-time Chicago gang czar’s room sat a male orderly and a nurse.

The gangster chief came here secretly yesterday from the federal prison at Lewisburg, Pa., and entered the general hospital as the patient of Dr. Joseph E. Moore, former director of the syphilis division of the John Hopkins Medical Clinic.

Capone is suffering from paresis – softening of the brain – but it was learned that, while his condition was serious, he was in no immediate danger.

The extent of Capone’s brain affliction remained a medical secret after his physician issued the first formal statement in the case, noting only that the former Chicago gangster “is ill and is in need of hospital care.”

The statement, issued over the names of Dr. Moore and Dr. Clyde D. Frost, Union Memorial director, said “public interest is such as to make it very difficult for him to receive the treatment he needs… We ask cooperation in this situation to avoid serious injury to the patient’s condition and grave disturbance to his family…”

Chicago police intensified their investigation of a possible link between Capone’s old organization and last week’s shotgun slaying of Edward J. O’Hare, president of the Sportsman’s Park race track.

Capone left Sunday night from Terminal Island prison, San Pedro, Calif., where he had been transferred from Alcatraz because of his physical condition. With his guards, he left the train at Harrisburg, Pa., and motored to Lewisburg, where he was formally released.

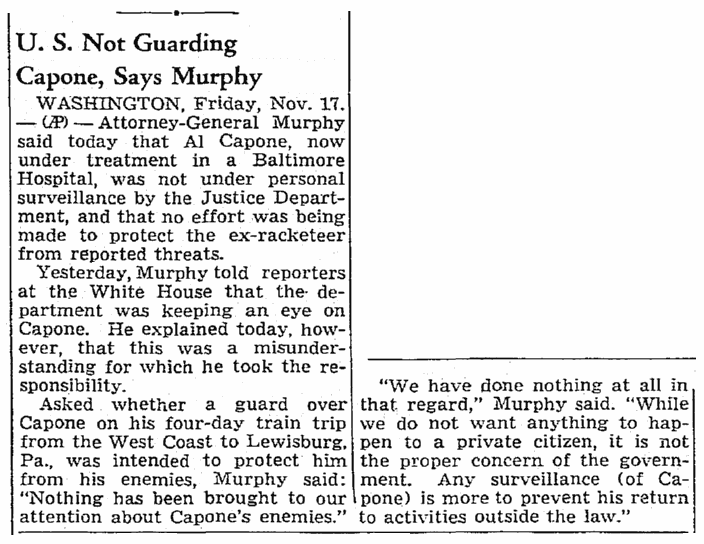

Here is a transcription of this article:

U.S. Not Guarding Capone, Says Murphy

WASHINGTON, Friday, Nov. 17 – (AP) – Attorney-General Murphy said today that Al Capone, now under treatment in a Baltimore Hospital, was not under personal surveillance by the Justice Department, and that no effort was being made to protect the ex-racketeer from reported threats.

Yesterday, Murphy told reporters at the White House that the department was keeping an eye on Capone. He explained today, however, that this was a misunderstanding for which he took the responsibility.

Asked whether a guard over Capone on his four-day train trip from the West Coast to Lewisburg, Pa., was intended to protect him from his enemies, Murphy said: “Nothing has been brought to our attention about Capone’s enemies.”

“We have done nothing at all in that regard,” Murphy said. “While we do not want anything to happen to a private citizen, it is not the proper concern of the government. Any surveillance (of Capone) is more to prevent his return to activities outside the law.”

Related Article: