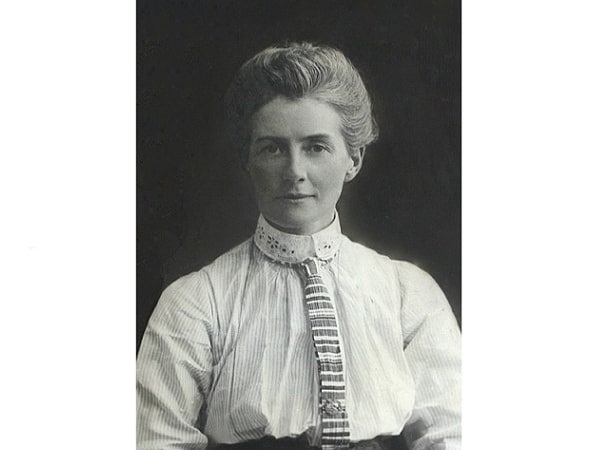

Introduction: In this article – in honor of March being Women’s History Month – Gena Philibert-Ortega writes about a British heroine from WWI, nurse Edith Cavell. Gena is a genealogist and author of the book “From the Family Kitchen.”

We often mistakenly think that women were not involved in wars prior to World War II (when women could join the military as WACs and WAVEs). However, women were on the battle front long before WWII, working as nurses and as soldiers – as in the case of the American Civil War, when some women joined military units dressed as men.

With war comes the possibility of death, even for nurses who are in non-combat roles. World War I saw women working as nurses, which put them at danger. In a few cases, women were executed during the war. The most well-known example is the work and execution of British nurse Edith Cavell.

Edith Cavell (1865-1915)

Edith Cavell was born on 4 December 1865 in Swardeston, Norfolk, England. She began her work life as a governess in Belgium, but after taking care of her father during an illness she was inspired to become a nurse. She worked in hospitals before accepting a position in Belgium at a “training hospital and school for nurses.”

When World War I broke out she was in England visiting her mother and decided it was time for her to return to Belgium. (1) Eventually the Germans occupied Belgium and Edith’s training hospital became a Red Cross hospital helping soldiers on both sides of the conflict. Nurse Cavell not only provided medical aid to all soldiers, regardless of which side they were on, but she also assisted the escape of Allied soldiers across the border to neutral Holland. She is credited with saving the lives of 200 soldiers. (2)

The Germans began to suspect that she was doing more than just nursing, and on 5 August 1915 she was arrested and imprisoned. (3)

The Execution of Edith Cavell

Cavell was charged, court martialed, and found guilty of treason by the Germans for her part in aiding enemy soldiers of Germany, even though she was not a German citizen. Cavell didn’t deny the charges and openly confessed.

After being sentenced to death, diplomats from neutral countries like the United States and Spain tried to convince the Germans to spare her life, but to no avail.

The night before her execution she told an Anglican chaplain:

“Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

With her final words before her death, Cavell said she was willing to die for her country. (4) On 12 October 1915, Edith Cavell was shot to death. (5)

International Outrage

Like the reaction to Germany sinking the Lusitania earlier in the year, the execution of Edith Cavell was used to inflame hatred toward the Germans, which in turn mobilized allies. The murky details of Cavell’s execution, including the story of her fainting and then being shot in the head by a German officer with a revolver, outraged civilians and leaders alike. These stories encouraged the idea that Germans were brutal monsters.

Newspaper opinion writers weighed in with articles that questioned what type of people execute women. Acknowledging that she may have been involved in helping allied soldiers, this writer said that, as a woman, Cavell should have been dealt with differently:

“When a war degenerates to the willful slaughter of women and children it is time to stop it. Nations cannot afford to have such crimes charged against them in the histories of future ages. Men who kill one another in battle, risking their own lives in strife with an enemy on equal terms, may be accredited with all the heroic qualities of courage and manhood: but no such ascription may be accorded the others who slay women and children; and there never was a cause so holy that it could justify such acts.”

Edith Cavell, like the victims of the Lusitania, began appearing in propaganda posters – which in turn helped to recruit additional soldiers. Her sacrifice made an impact and influenced British men. The week after her execution, British military recruitment doubled from 5,0000 to 10,000 soldiers. (6)

Baron Oskar von der Lancken, the chief of Germany’s Political Department at Brussels during the occupation of Belgium – referred to as the “assassin of Edith Cavell” – was still defending himself in the 1930s against accusations that he didn’t do enough to stop the execution of Cavell. In this newspaper article, he blames the United States, who did not enter World War I until 1917, for not intervening in a timely manner so that he could convince authorities to stop the execution.

Von der Lancken said of the secretary of the U.S. Legation to Belgium, Hugh Gibson:

“The guilt for asking for my intervention only at a moment when it was too late to take any effective steps for the pardon of Miss Cavell falls upon the American Legation, particularly upon Mr. Gibson… It was up to Gibson, who knew more about the sentence on Miss Cavell and the danger she was in, to call for my intervention at the right time.”

Von der Lancken continued:

“My intervention against the execution of Miss Cavell had first of all only political and to a smaller degree general humane motives when I urged General von Sauberzweig to accept the appeal for mercy. Her heroism was apparent to me only later, and my regret at not having been able to save her was all the greater.”

Edith Cavell was not the only woman that the Germans arrested or executed for espionage during World War I. Other women included Louise de Bettignies and Gabrielle Petit. Today, Cavell is known for her care of soldiers on both sides of the battlefield and her heroism. Cavell is honored with numerous memorials in England, Canada, Australia, and Belgium.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers. Did any of your ancestors serve in WWI? Please share your stories with us in the comments section.

_________________

(1) “Who was Edith Cavell,” Imperial War Museum (https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/who-was-edith-cavell)

(2) “Who was Edith Cavell,” Cavell Nurses’ Trust (https://www.cavellnursestrust.org/edith-cavell)

(3) Ibid.

(4) “Edith Cavell,” Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Cavell)

(5) “British Nurse Edith Cavell executed,” History (https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/british-nurse-edith-cavell-executed)

(6) “Nurse Edith Cavell and the British World War One propaganda campaign,” BBC News http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-norfolk-34401643