Introduction: In this article – in honor of the approaching Fourth of July celebrations – Jane Hampton Cook searches old newspapers to learn more about the new nation’s first Independence Day celebration. Jane is a presidential historian and author of ten books, including Stories of Faith and Courage from the Revolutionary War. Her works can be found at Janecook.com. She is also the host of Red, White, Blue and You.

For centuries Americans have celebrated Independence Day on July 4, as well they should. That was the day in 1776 when the Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence to free America from British rule.

However, old newspaper articles report that Virginians first celebrated independence on 16 May 1776, through a parade, picnic, toasts to America’s independent states, and even fireworks. How was this possible?

On May 15, the day before, 112 men attended a convention in Williamsburg, Virginia. Their goal was to give instructions to the Virginia delegates of the Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia.

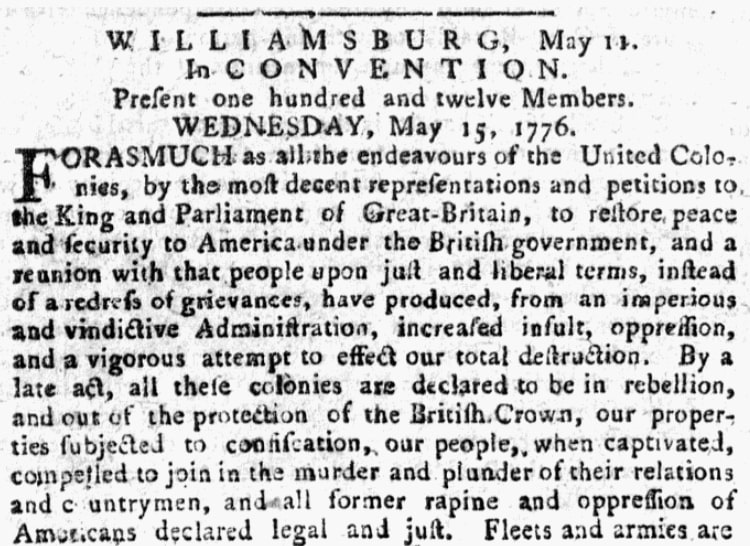

As this article reported, the convention evaluated their current circumstances and recalled their past endeavors to reconcile with Great Britain:

“For as much as all the endeavors of the United Colonies, by the most decent representations and petitions to the King and Parliament of Great Britain, to restore peace and security to America under the British government, and a reunion with that people under just and liberal terms, instead of a redress of grievances, have produced, from an imperious and vindictive Administration, increased insult, oppression, and a vigorous attempt to effect our total destruction.”

A year earlier the Continental Congress had sent King George III an Olive Branch Petition. Without even reading it, the king had declared war on the colonies. Virginians had experienced his wrath, as the article reported:

“By a late act, all these colonies are declared to be in rebellion, and out of the protection of the British Crown, our properties subjected to confiscation, our people, when captivated [i.e., made captive], compelled to join in the murder and plunder of their relations and countrymen, and all former rapine and oppression of Americans declared legal and just. Fleets and armies are raised, and the aid of foreign troops engaged to assist these destructive purposes.”

At the time of the convention, the royal governor of Virginia was sailing on an armed ship and seizing property along the coast and rivers of Virginia. The delegates’ choices were dire, as the article reported:

“In this state of extreme danger, we have no alternative left but an abject submission to the will of those overbearing tyrants, or a total separation from the Crown and government of Great Britain, uniting and exerting the strength of all America for defense, and forming alliances with foreign powers for commerce and aid in War.”

The Virginians unanimously voted on a resolution:

“That the delegates appointed to represent this colony in General Congress be instructed to propose to that respectable body TO DECLARE THE UNITED COLONIES FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES.”

They proposed that the Continental Congress issue a declaration of rights to “secure substantial and equal liberty to the people.”

These 112 Virginians were so happy and joyous that they took up a collection of money to celebrate with pageantry and treat the soldiers in town to a feast – the new nation’s first Independence Day celebration, nearly two months before the Fourth of July!

The next day, on 16 May 1776, the soldiers:

“…paraded in Waller’s Grove, before Brigadier General Lewis, attended by the gentlemen of the Committee of Safety, the members of the General Convention, the inhabitants of this city, &c.”

After reading the resolution aloud to the Army, they toasted the American independent states, the Continental Congress, and General Washington “and victory to the American arms.” In joyful response, they discharged artillery and small arms, and shouted acclamations.

Instead of flying the Union Jack of Great Britain, they raised a new flag with thirteen red and white stripes with a small version of the British flag in the upper left-hand corner.

How did the celebration end? With fireworks, of course:

“…the evening concluded with illuminations, and other demonstrations of joy, everyone seeming pleased that the domination of Great Britain was now at an end, so wickedly and tyrannically exercised for these twelve or thirteen years past, notwithstanding our repeated prayers and remonstrances of redress.”

A few weeks after this independence celebration in Virginia, the Continental Congress heard the resolution from the Virginia delegates for declaring independence and assigned the resolution to a committee for consideration. They also established a committee for writing a declaration of rights. With editorial assistance from Ben Franklin and John Adams, Virginian Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence.

The Continental Congress approved the resolution for independence on July 2, which led John Adams to predict the following in a letter to his wife Abigail:

“The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.”

Although 4 July 1776 became the anniversary date, because Congress approved the finalized Declaration of Independence then, Adams accurately predicted how Independence Day would be celebrated.

Adams wrote:

“I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

Perhaps Jefferson or one of the other Virginia delegates had shared with Adams how Virginians had already celebrated Independence on May 16. Or maybe he read about it in the Pennsylvania Evening Post. Regardless, a tradition was born.

Note: An online collection of newspapers, such as GenealogyBank’s Historical Newspaper Archives, is not only a great way to learn about the lives of your ancestors – the old newspaper articles also help you understand American history and the times your ancestors lived in, and the news they talked about and read in their local papers.

Related Article: